Ntozake Shange, a spoken-word artist who morphed into a playwright with her canonical play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf,” died on Saturday in Bowie, Md. She was 70.

Her death was confirmed by her sister Ifa Bayeza, who said she had been in fragile health since a pair of strokes more than a decade ago.

Only 27 years old when “For Colored Girls” opened at the Booth Theater in 1976, Ms. Shange was a Broadway rarity on two counts: She was black and she was a woman. But her unconventional play was a hit and nominated for a Tony Award. A series of searing feminist monologues for seven black female characters named for the colors of the rainbow — Ms. Shange herself played the Lady in Orange — it inspired generations of playwrights coming up behind her.

Among them was the Pulitzer Prize winner Suzan-Lori Parks, who in an interview on Sunday spoke fondly of encountering Ms. Shange in September at the Park Avenue Armory, at a brunch for playwrights.

“I saw Ntozake enter the room,” Ms. Parks said, “and I stood up, and the younger playwrights said, ‘What’s the matter? Why are you standing?’ And I said, ‘The queen has just entered the room.’ ”

In her work, Ms. Shange was a champion of black women and girls, and in her trailblazing, she expanded the sense of what was possible for other black female artists.

When Ms. Shange (her full name is pronounced en-toh-ZAH-kee SHAHN-gay) first arrived in the American theater, though, the response was not uniformly reverent. “For Colored Girls” won admiring reviews and an Obie Award for a production at the Public Theater, before it moved to Broadway. But the play’s forthright, personal discussion of trauma and abuse experienced by black women was taken by some as an affront to black men.

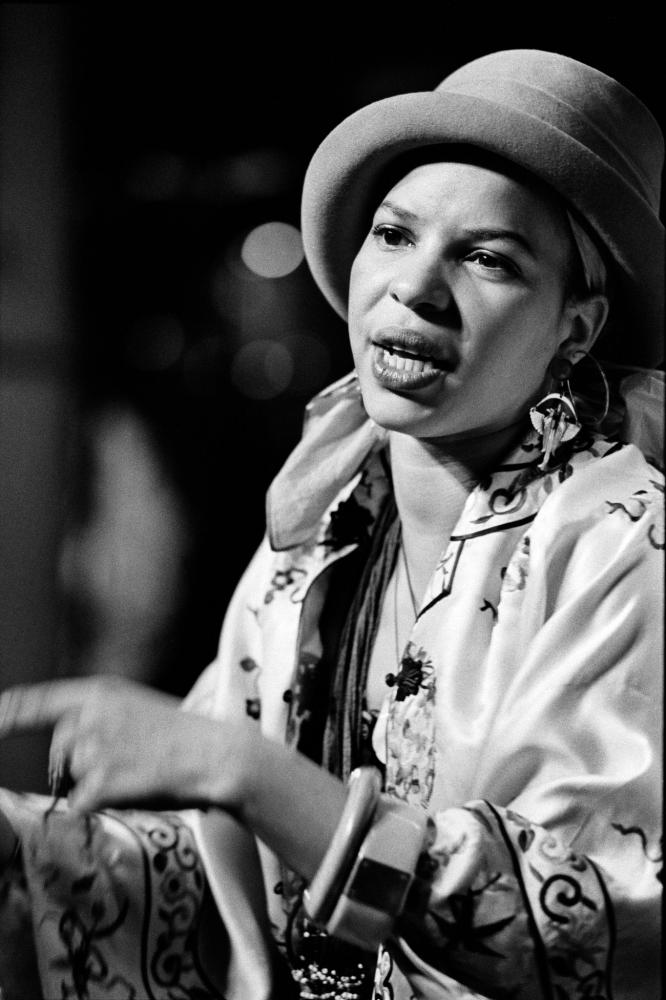

Credit: Marilynn K. Yee/The New York Times

“There was quite a ruckus about the seven ladies in their simple colored dresses,” Ms. Shange wrote decades later. “I was truly dumbfounded that I was right then and there deemed the biggest threat to black men since cotton pickin’, and not all women were in my corner, either.”

Born Paulette Williams on Oct. 18, 1948, in Trenton, she was the daughter of Dr. Paul T. Williams, a surgeon, and Eloise Owens Williams, a professor of social work. She adopted a Zulu name as a young woman.

She was a graduate of Trenton High School, Barnard College and the University of Southern California, where she earned a master’s degree in American studies.

Her family said she had been affected deeply by the civil rights movement and had later participated in the antiwar movement and efforts to advance the rights of women, Puerto Ricans and black artists.

A novelist and poet who was unable to hold a pen for several years after suffering strokes, Ms. Shange had recently been giving poetry readings again, and she was working on a new book about dance. She had been pushing herself hard, though, and the activity depleted her, Ms. Bayeza said in a phone interview.

“The intensity with which she embraced life took its toll on her body,” Ms. Bayeza said. “The vulnerability that she was so willing to share with the world was still a vulnerability.”

Ms. Shange, whose adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children” won an Obie citation, was the author of 15 plays, 19 poetry collections, six novels five children’s books and three essay collections. One of her novels, “Some Sing, Some Cry,” was written with Ms. Bayeza and told the history of African-American music and dance through seven generations of a fictional family.

It is an oeuvre all the more remarkable given what her family described as Ms. Shange’s struggles with bipolar disorder and addiction.

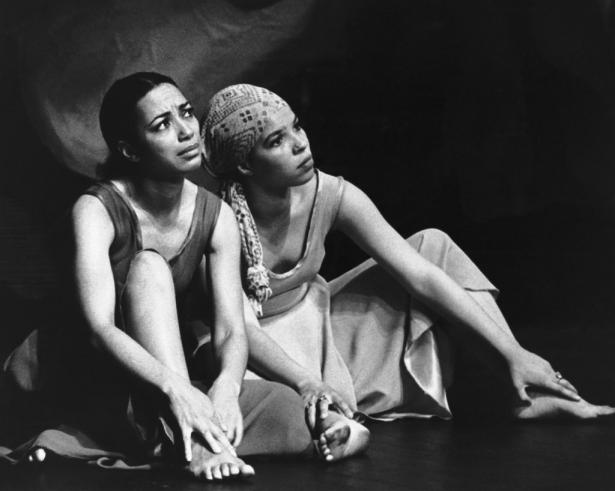

Credit: Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

But “For Colored Girls” has remained her best known work. In 1982, it was an American Playhouse production on PBS, and in 2010 it became a star-studded film adaptation directed by Tyler Perry.

The cast included Janet Jackson, Kerry Washington, Phylicia Rashad, Anika Noni Rose and Whoopi Goldberg. Madea, Mr. Perry’s onscreen alter ego, was nowhere to be seen. “Ms. Shange said she explicitly told Mr. Perry that Madea could not be in ‘Colored Girls,’” The Times reported.

Ms. Shange referred to the play as a choreopoem because it combined poetry, dance and music.

Lynn Nottage, the two-time Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, said the play “definitely spoke to a generation of young women who didn’t feel invited into a theater space, who suddenly saw representation of themselves in a very honest way, and understood that they could occupy that space for the first time.”

It is also something of a rite of passage for black actresses, the Obie-winning playwright Aleshea Harris (“Is God Is”) said. Before she switched to playwriting, she played the Lady in Yellow in a Florida production. (Ms. Parks, too, is a veteran of the show, having played the Lady in Blue in a Texas production directed by Laurie Carlos, who originated that role on Broadway.)

Ms. Harris’s first encounter with the text was years earlier, though, and she remembers the feeling of recognition she had reading it as a college student.

“It was like electricity,” Ms. Harris recalled, “and I think I said out loud, ‘This sounds like me.’ It felt like she had taken it out of my mouth.”

Spread the word