The earliest lesson I learned about Martin Luther King Jr. was that he had “a dream.” Delivered in his most well-known speech at the 1963 March on Washington, as posed to me and as I understood clearly in my adolescent mind, that dream was a colorblind one.

That manufactured perspective — often told to young children and supported by mainstream, predominantly white commentators — was focused on erasing the divisions between black and white people, not necessarily by blaming white people for their participation in systems of anti-black racism, but by moving beyond racial difference altogether.

But that was never actually King’s dream. His was much more radical than that.

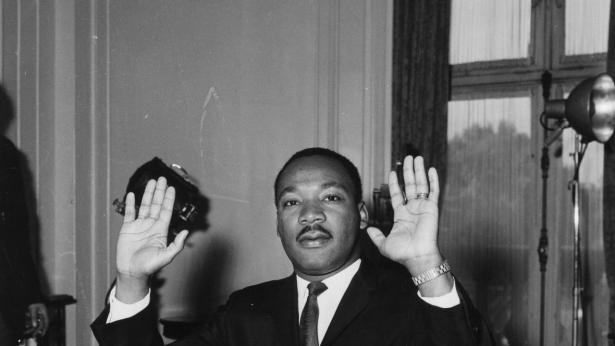

In 1954, King was finishing a doctoral dissertation at Boston University. Soon he was thrust into the political limelight early on in his career as a 25-year-old pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. The political moment necessitated a radical approach to politics — he was pastoring as Brown v. Board of Education was decided, effectively ending legal segregation in the United States.

This monumental civil rights win, and the promise of freedom of public movement for black Americans, signaled an era of struggle and triumph for King and those who believed in his nonviolent cause. On the heels of Brown, King was just 26 when he helped facilitate and lead the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which started on December 5, 1955, and lasted over a year.

It is estimated that the Montgomery bus lines lost 30,000 to 40,000 bus fares each day because of the boycott. For 381 days, boycotters walked or carpooled to and from their destinations. The boycott and a legal challenge forced the Montgomery City Lines bus company to desegregate their fleet by November 1956, which sparked years of nonviolent organizing in the South. It was King’s unconventional engagement tactics, organizing black communities through “direct actions” on buses, at lunch counters, libraries, and many other public facilities, that quickly elevated his name among national movement circles and mainstream media alike.

But this effort didn’t spring forth from nothing. Black women and girls like 15-year-old Claudette Colvin and 42-year-old Rosa Parks first refused to obey segregation laws on Montgomery buses that relegated black riders to the back rows and mandated they give up their seats to white riders, and had been gaining attention before its start. And the pressure-cooker–like conditions of many Southern cities stoked the flames of a burgeoning civil rights movement galvanized by the gruesome kidnapping and murder of 14-year-old Chicago-born Emmett Till while visiting family in Money, Mississippi, in August 1955. Till’s murder had a profound effect on King, as it represented the horrors of the anti-black racism he was bracing himself to stand against.

By 1963, the year four little girls were killed in cold blood by KKK members, King had already made frequent trips to Birmingham, Alabama, even getting arrested during his nonviolent protests of racial segregation with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

The sanitized version of King’s life and work — the colorblind “I have a dream” narrative — often fails to acknowledge how King’s increasing profile as a radical, anti-racist organizer drew antagonism from the FBI and its director at the time, J. Edgar Hoover, which began as early as 1964, four years before he was assassinated.

In fact, in October 1963, U.S. attorney general Robert F. Kennedy authorized secret wiretapping of King’s phones and kept the surveillance under wraps until a few weeks after the assassination. The FBI’s continued use of surveillance, in tandem with its efforts to defame King as a Communist sympathizer, hardly comports with passive stories one would expect of the peaceful, nonconfrontational character often described today. But rather than a truthful reckoning with his radical positions on justice, many cling to King’s earlier quotes and work, misrepresenting the full gamut of his contributions to the justice tradition. Just last year, the FBI attempted to “honor” King by quoting him on Twitter. Yet the bureau didn’t follow up its tweet with any explanation as to how such an honorable man was once one of its greatest adversaries.

King was a staunch antiwar activist and spoke firmly against U.S. militarism in the Vietnam War. In an April 1967 speech called “Beyond Vietnam,” King called the war “madness.” This was a deeply radical and polarizing opinion in a moment when protests of the war had begun erupting across the country in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. In no uncertain terms, King articulated his opposition to the war in Vietnam, saying, “I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic, destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.”

These opinions not only made him unpopular, as 64% of Americans approved of the war according to an October 1965 Gallup poll, they highlighted his increasing distance from mainstream American politics that called for the respectability, quiet assimilation, and “good” behavior of black Americans. In fact, polling during the 1960s reflects how polarizing King’s radical work truly was for U.S. citizens. In 1965, Gallup found that King had a 45% positive and 45% negative rating. And in 1966, the last year he was included in the poll, his positive rating dropped to 32% while his negative rating increased to 63%. However, by 2011, his rating was 94% positive. This vast swing in approval of King today isn’t rooted in his radical legacy. Rather, it is the product of generations of appropriation of his liberatory work and a whitening of his effort to ensure more freedom for those least likely to attain it in the United States.

Figures like President Barack Obama have reminded us that King once said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But over time, the great orator’s writings became less magnanimous and ever more convinced that white supremacy was the most significant obstacle in attaining liberation for all black people.

In his final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, originally published in 1967, King wrote that “Whites, it must frankly be said, are not putting in a similar mass effort to reeducate themselves out of their racial ignorance. It is an aspect of their sense of superiority that the white people of America believe they have so little to learn. The reality of substantial investment to assist Negroes into the twentieth century, adjusting to Negro neighbors and genuine school integration, is still a nightmare for all too many white Americans.”

He continued: “These are the deepest causes for contemporary abrasions between the races. Loose and easy language about equality, resonant resolutions about brotherhood fall pleasantly on the ear, but for the Negro there is a credibility gap he cannot overlook. He remembers that with each modest advance the white population promptly raises the argument that the Negro has come far enough. Each step forward accents an ever-present tendency to backlash.”

By this point in his life, King had abandoned the rose-colored glasses of his youth. Instead, he was laser-focused on addressing white supremacy in its basest and most intimate forms: in communities, schools, and neighborhoods. This departure from his colorblind rhetoric of yore was an indication that King was becoming politicized by his experiences in the movement.

Essentially, he was getting woke.

King’s beliefs in a more radical vision for America became manifest in his later social organizing work. In early 1968, King planned the Poor People’s Campaign, a march on Washington, D.C., meant to demand greater attention to the economic disparities between class groups, disparities that most frequently had a disproportionate effect on black people. The campaign had a radical vision, one that demanded access to housing, employment, and health care for those historically denied those rights. While it had no specific racial target, it challenged Congress to pass sweeping anti-poverty legislation.

Unfortunately, King was killed before he was able to complete the Poor People’s March. He was 39 years old. While as many as 50,000 people marched on Washington, the effort fizzled out with King’s leadership as thenation mourned his death.

This Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we would do his memory justice by honoring all of his legacy. Not just the parts that make white Americans comfortable.

Spread the word