If Martin Luther King Jr. still lived, he’d probably tell people to join unions.

King understood racial equality was inextricably linked to economics. He asked, “What good does it do to be able to eat at a lunch counter if you can’t buy a hamburger?”

Those disadvantages have persisted. Today, for instance, the wealth of the average white family is more than 20 times that of a black one.

King’s solution was unionism.

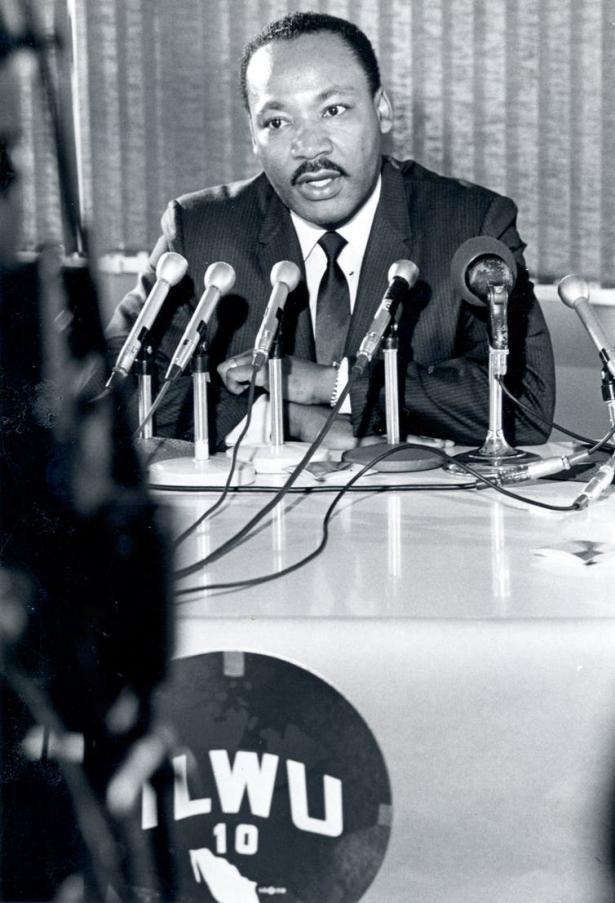

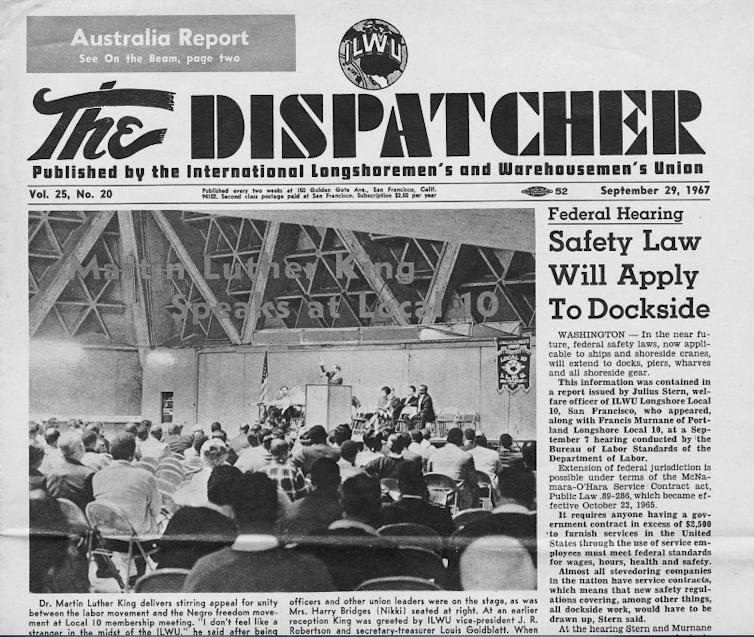

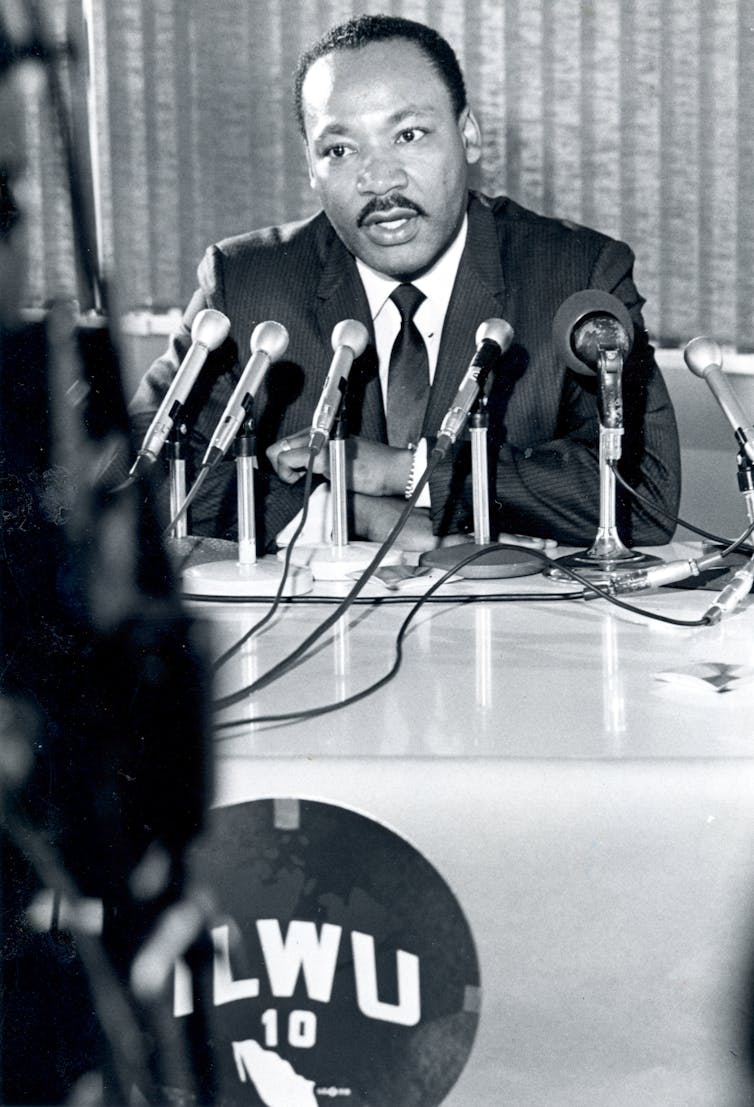

The union newspaper reported that King appealed in his Sept. 21, 1967 address to Local 10 ‘for unity between the labor movement and the Negro freedom movement.’ The Dispatcher archives, ILWU

Convergence of needs

In 1961, King spoke before the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest and most powerful labor organization, to explain why he felt unions were essential to civil rights progress.

“Negroes are almost entirely a working people,” he said. “Our needs are identical with labor’s needs – decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.”

My new book, “Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area,” chronicles King’s relationship with a labor union that was, perhaps, the most racially progressive in the country. That was Local 10 of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, or ILWU.

ILWU Local 10 represented workers who loaded and unloaded cargo from ships throughout San Francisco Bay’s waterfront. Its members’ commitment to racial equality may be as surprising as it is unknown.

In 1967, the year before his murder, King visited ILWU Local 10 to see what interracial unionism looked like. King met with these unionists at their hall in a then-thriving, portside neighborhood – now a gentrified tourist area best known for Fisherman’s Wharf, Pier 39.

While King knew about this union, ILWU history isn’t widely known off the waterfront.

Civil rights on the waterfront

Dockworkers had suffered for decades from a hiring system compared to a “slave auction.” Once hired, they routinely worked 24 to 36 hour shifts, experienced among the highest rates of injury and death of any job, and endured abusive bosses. And they did so for incredibly low wages.

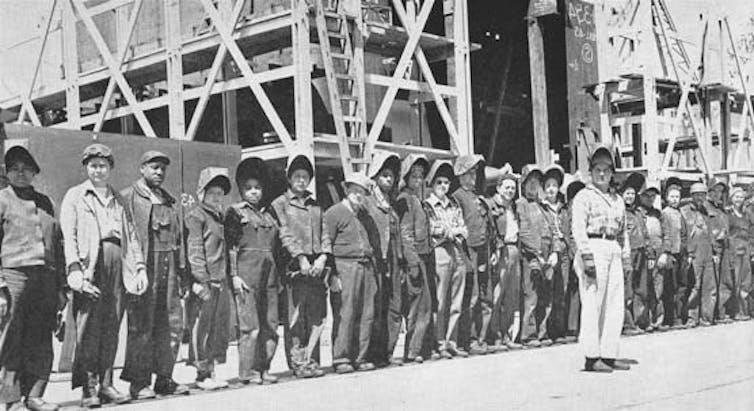

Marching in the San Francisco Waterfront Strike of 1934. San Francisco Public Library

In 1934, San Francisco longshoremen – who were non-union since employers had crushed their union in 1919 – reorganized and led a coast-wide “Big Strike.”

In the throes of the Great Depression, these increasingly militant and radicalized dockworkers walked off the job. After 83 days on strike, they won a huge victory: wage increases, a coast-wide contract and union-controlled hiring halls.

Soon, these “wharf rats,” among the region’s poorest and most exploited workers, became “lords of the docks,” commanding the highest wages and best conditions of any blue-collar worker in the region.

At its inception, Local 10’s membership was 99 percent white. But Harry Bridges, the union’s charismatic leader, joined with fellow union radicals to commit to racial equality in its ranks.

Originally from Australia, Bridges started working on the San Francisco waterfront in the early 1920s. It was during the Big Strike that he emerged as a leader.

Bridges coordinated during the strike with C.L. Dellums, the leading black unionist in the Bay Area, and made sure the handful of black dockworkers would not cross picket lines as replacement workers. Bridges promised they would get a fair deal in the new union. One of the union’s first moves after the strike was integrating work gangs that previously had been segregated.

Local 10 overcame pervasive discrimination

Cleophas Williams, a black man originally from Arkansas, was among those who got into Local 10 in 1944. He belonged to a wave of African-Americans who, due to the massive labor shortage caused by World War II, fled the racism and discriminatory laws of the Jim Crow South for better lives – and better jobs – outside of it. Hundreds of thousands of blacks moved to the Bay Area, and tens of thousands found jobs in the booming shipbuilding industry.

Black workers in shipbuilding experienced pervasive discrimination. Employers shunted them off into less attractive jobs and paid them less. Similarly, the main shipbuilders’ union proved hostile to black workers who, when allowed in, were placed in segregated locals.

A few thousand black men, including Williams, were hired as longshoremen during the war. He later recalled to historian Harvey Schwartz: “When I first came on the waterfront, many black workers felt that Local 10 was a utopia.”

During the war, when white foremen and military officers hurled racist epithets at black longshoremen, this union defended them. Black members received equal pay and were dispatched the same as all others.

A gang of welders at the Marinship yard, Sausalito, California, in around 1943. National Park Service

For Williams, this union was a revelation. Literally the first white people he ever met who opposed white supremacy belonged to Local 10. These longshoremen were not simply anti-racists, they were communists and socialists.

Leftist unions like the ILWU embraced black workers because, reflecting their ideology, they contended workers were stronger when united. They also knew that, countless times, employers had broken strikes and destroyed unions by playing workers of different ethnicities, genders, nationalities and races against each other. For instance, when 350,000 workers went out during the mammoth Steel Strike of 1919, employers brought in tens of thousands of African-Americans to work as replacements.

Some black dockworkers also were socialists. Paul Robeson, the globally famous singer, actor and left-wing activist had several friends, fellow socialists, in Local 10. Robeson was made an honorary ILWU member during WWII.

King speaks at Local 10 in San Francisco, September 1967. ILWU Archives, Author provided

Martin Luther King, union member

In 1967, King walked in Robeson’s footsteps when he was inducted into Local 10 as an honorary member, the same year Williams became the first black person elected president of Local 10. By that year, roughly half of its members were African-American.

King addressed these dockworkers, declaring, “I don’t feel like a stranger here in the midst of the ILWU. We have been strengthened and energized by the support you have given to our struggles. … We’ve learned from labor the meaning of power.”

Many years later, Williams discussed King’s speech with me: “He talked about the economics of discrimination. … What he said is what Bridges had been saying all along,” about workers benefiting by attacking racism and forming interracial unions.

Eight months later, in Memphis to organize a union, King was assassinated.

The day after his death, longshoremen shut down the ports of San Francisco and Oakland, as they still do when one of their own dies on the job. Nine ILWU members attended King’s funeral in Atlanta, including Bridges and Williams, honoring the man who called unions “the first anti-poverty program.”![]()

Peter Cole, Professor of History, Western Illinois University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Spread the word