Toward the end of the third episode of The Loudest Voice, the Fox News impresario Roger Ailes (played by Russell Crowe), his wife, Beth (Sienna Miller), and their 8-year-old son, Zach, clamber into the back of a chauffeur-driven SUV for a summer tour of Ailes’s hometown. “Heartland of the country, here we go,” Ailes says benevolently, like a clean-shaven Santa. The next shots in the Showtime series are of abandoned factories, piles of trash discarded on the street, and decaying homes. Beth’s face wrinkles, as if she smells something; Zach looks frightened. Later, when someone asks Beth what she thinks of Warren, Ohio, she looks around, composes herself, and says sunnily, “Any town that made Roger Ailes is great in my book.”

This disconnect, the palpable condescension and disgust the Ailes family feel for the communities and viewers who’ve made them impossibly rich, is one of the most intriguing and under-explored parts of The Loudest Voice, a seven-part miniseries based on Gabriel Sherman’s 2014 Ailes biography. Over the course of the first four episodes made available for review, Ailes launches Fox News, which he molds into a juggernaut—a ratings powerhouse and a virtual klaxon blasting nonstop narratives of American decline. With Fox, Ailes tells his team during a charged 4 a.m. meeting prior to launch, they can “reclaim the real America.” Meanwhile, he goes home at night to a fortress 50 miles north of New York City, with steel doors and keypads barricading off his and Beth’s bedroom from the chaos he’s fomented in the rest of the country.

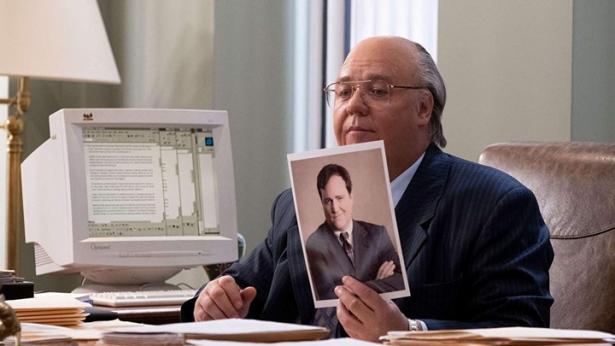

In part, this is because Crowe’s performance oscillates between leering plutocrat and raving paranoiac, without nailing the fanaticism in between that made Ailes’s vision of America so contagious. There’s nothing in the earliest episodes about his origins as a production assistant on local television, or his entry into politics repackaging Richard Nixon into a more telegenic product. The series begins as Ailes, having been pushed out of his role at CNBC, goes to work for the media magnate Rupert Murdoch (Simon McBurney). His vision is to make Fox News a cable channel for what he sees as the underserved conservative viewers of America, and Murdoch, swayed by the promise of tapping into a whole new market, concedes.

From the very beginning, there’s tension between Murdoch’s profiteering interests and Ailes’s ideological convictions. The second episode jumps forward to 2001, when the events of 9/11 seemed to further exacerbate Ailes’s most reactionary and bigoted tendencies. (Introduced to a Saudi prince at one of Murdoch’s red-carpet events, Ailes says, “I’m just glad you didn’t hit any buildings on the way in.”) As he watches the second plane hit the World Trade Center, Crowe’s expression as Ailes curdles into a strange combination of fury and excitement. While other networks elect not to air footage of people jumping from the buildings, Ailes insists that Fox run it. “We need everyone in the goddamn world to see what these animals have done to us,” he snarls.

The series cycles through 2008, when Barack Obama’s nomination as the Democratic candidate for president seemed to send Ailes—and Fox—into an even more poisonous frenzy, and through the first year of Obama’s presidency, when Ailes began stoking the birther movement that questioned the former senator’s citizenship. There are allusions to Ailes’s own paranoia at this time, but not the full extent of it—like the bunker he installed underneath his homewith six months’ worth of survival rations, and the trees he removed around the property to have a clear view should any leftist groups attack. The Loudest Voiceseems more intent on probing the political and sociological impact of Fox News than the ferociously complicated psychology of the man who created it. It’s a worthy mission, but it leaves the character at the center of the series at something of a distance. Is he a true iconoclast, or just an opportunist? Does he truly believe in the battle between good and evil he sells every day on cable news, or does he simply get a puissant thrill from winning?

One of The Loudest Voice’s subplots explores Roger and Beth’s heavy-handed mission to take over the local newspaper in their upstate town of Garrison, New York. What starts as a casual side project to occupy Beth’s free time quickly becomes a microcosm of what Fox News is doing nationally, pitting residents against one another and stirring up toxic enmity over issues like zoning laws and property taxes. “Are you proud of yourself?” a woman asks Ailes’s hand-selected editor in chief (played by Emory Cohen) at a community meeting. “You’re tearing this town apart.” As a summation of Ailes’s long-term impact, though, it’s barely even a preview.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

SOPHIE GILBERT is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers culture.

Spread the word