Editors’ note: “If it happened yesterday, we’ve already forgotten”—an anonymous Nation editor.

What we see and react to in the media conditions us to view the present as a series of immediate crises, and to ignore their roots in the past. For social justice movements, this can be deadly, cutting us off from an ability to weigh and learn from our own history, and to understand how that history shapes the ways we fight for justice today.

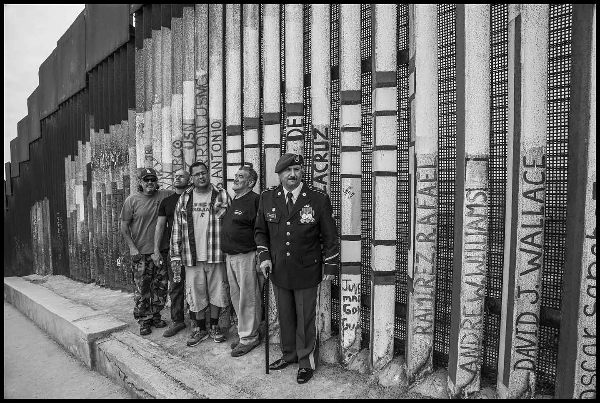

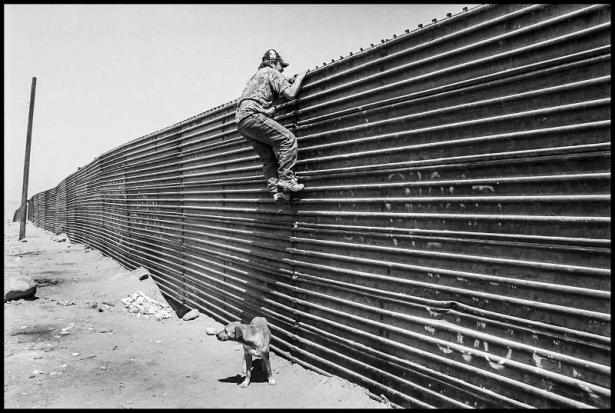

In this photo essay, David Bacon reaches into his photographic archive of 30 years, which are now part of the Special Collections of Stanford University’s Green Library. A Nation contributor and former union organizer, Bacon, through his photographs and journalism, has documented the courage of people struggling for social and economic justice in countries around the world.

* * *

In 1971, Pat Nixon, wife of Republican President Richard Nixon, inaugurated Border Field State Park, where the border meets the Pacific Ocean just south of San Diego. The day she visited, she asked the Border Patrol to cut the barbed wire so she could greet the Mexicans who’d come to see her. She told them, “I hope there won’t be a fence here too much longer.”

Instead, a real fence was built in the early 1990s, made of metal sheets taken from decommissioned aircraft carrier landing platforms. The sheets had holes, so anyone could peek through to the other side. But for the first time, people coming from each side could no longer physically mix together or hug each other. This is how the wall looked when I began photographing it, almost 30 years ago.

That old wall still exists in a few places on the Mexican side in Tijuana and elsewhere. But Operation Gatekeeper, the Clinton administration border enforcement program, sought to push border crossers out of urban areas like San Ysidro into remote desert regions where crossing was much more difficult and dangerous. To do that, the government had contractors build a series of walls that were harder to cross.

That’s partly how the US-Mexico border became more than mere geography—how it became instead a passage of fire, an ordeal that must be survived in order to send money from work in the United States back to a hungry family, to find children and relatives from whom they have been separated by earlier journeys, or to flee an environment that has become too dangerous to bear.

credit: David Bacon

Some do not survive, dying as they try to cross the desert or swim the Rio Bravo. To them the border region has become a land of death. Every year at least 300–400 people die trying to cross, and are buried, often without names, in places like the graveyard in Holtville, in the Imperial Valley.

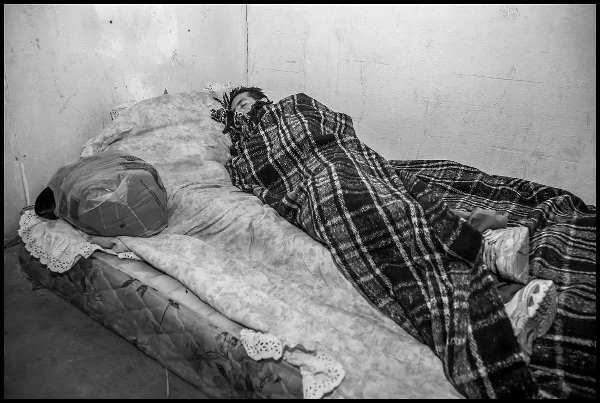

But the photographs I’ve taken over 30 years also show that the US/Mexico border is a land of the living. Millions of people live and work on Mexico’s side of the border: There are the child laborers who pick the tomatoes and strawberries in Mexicali Valley that line the shelves of US grocery stores; there are the workers from across Mexico who staff the massive maquiladoras in Tijuana; and there are thousands who have been deported to Mexico, and who must now somehow also survive this passage of fire.

I saw my first immigration raid long before I became a photographer. I was an organizer for the United Farm Workers in the Coachella Valley. One morning, I drove out to a grove of date palms to talk with the palmeros working high in the trees. As I pulled my old white Valiant (the only kind of car the union had) down a row between the palms, I saw a green Border Patrol van. The workers I’d talked with the night before in the union hall were all staring at the ground, handcuffed behind their backs.

I felt helpless to stop the inexorable process. I chased the van to the holding center in El Centro, two hours drive south, but then stood outside the barbed wire. I asked myself what would happen to those deported and what I could do to help the families left behind.

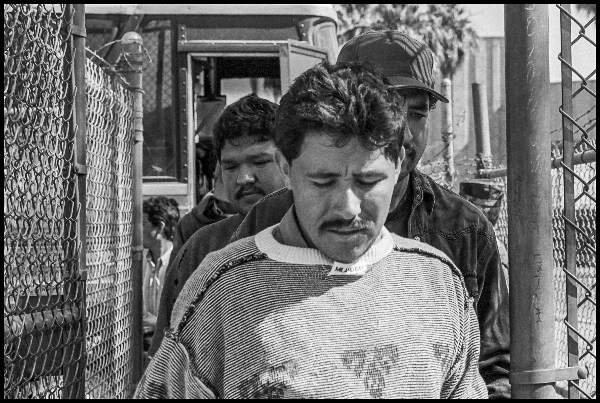

When I began working as a writer and photographer, I tried to use my camera to find answers to those questions. I carry the camera as a tool to help stop the abuse, and to take photographs that will help people organize. The photographs, therefore, try to give personality and presence to deportees and their families, and to those who support them.

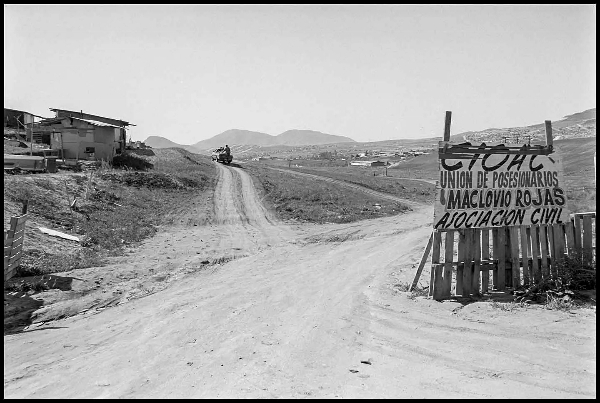

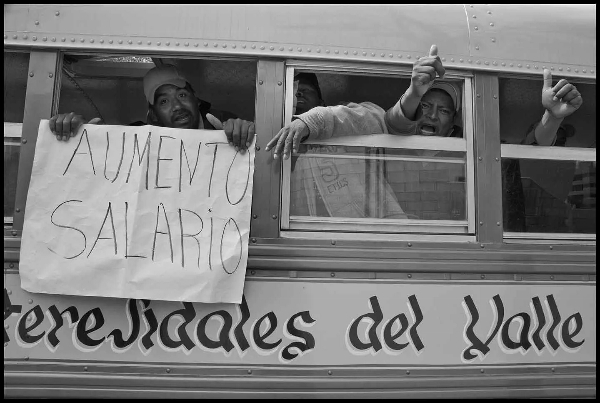

So that’s where I began, with the knowledge that the border is not some region of docile subsistence but one of struggle and resistance. Workers in Tijuana’s maquiladoras have organized their unions, and their strikes continue to shake the factories along the border. The laborers in Mexico’s San Quentin Valley, in a historic strike in 2015, formed the first independent union for farm workers in Mexico’s border region. Deportees, returning to the country after their time in the United States—whether mere days or most of a lifetime—have organized to make survival easier, and ultimately to protest the system that forced them over the border. In one example, the group Border Angels helped migrants take over the Migrant Hotel in Mexicali to give shelter and food to people as they’re forced back through the border gate. Even the park next to the Tijuana River became a protest site, as homeless migrants and deportees joined city activists to stop its privatization, at the same time as they lived on the site in an Occupy-style protest.

At every point along the border where there is hardship, there is also resilience, and strength, and a willingness to fight to not just survive but to thrive.

Today, Border Field State Park looks quite a bit different than it did that day Pat Nixon shook hands across the barbed wire. The aircraft landing strips were replaced in 2007 by an 18-foot wall of vertical metal columns. Two years later, a second wall was built on the US side, right behind the first. The area between them became a security zone where the Border Patrol restricts access to just four hours on Saturday and Sunday. The metal columns now extend into the Pacific surf.

Playas de Tijuana, though, on the Mexican side of the wall, is the city’s beach suburb. There the wall is just a sight to see for the hundreds of people who come out to the sand on the weekend. The seafood restaurants are jammed, and sunbathers set up their umbrellas near the surf. Occasionally, a curious visitor will walk up and look through the bars into the United States. I don’t know what will come next for the borderlands—if Trump will get his way and spend billions to extend the wall across more of the border, if Border Patrol patrols will force migrants to seek out even more inhospitable routes, if a “renegotiated” NAFTA will continue the exploitation of Mexican laborers for US profits—but I will continue to document this land of the living as long as I’m able.

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

Photo: David Bacon

[David Bacon is author of Illegal People—How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants (2008), and The Right to Stay Home (2013), both from Beacon Press.]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Copyright c 2019 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $9.50!

Spread the word