A Democratic Socialist’s Fifty-Year Adventure. By Milt Tambor. Self-published, 2019, 95pp. (Order on line, $5.)

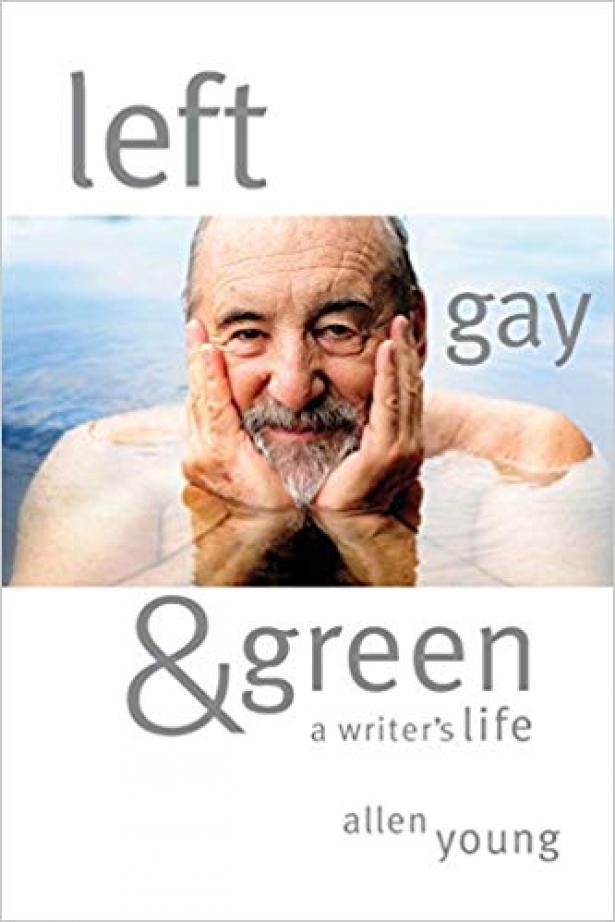

Allen Young, Left, Gay and Green: a Writer’s life. North Charleston, SC: Create Space, 2018, 480pp. $25.

The historical moment for 1960s radicals’ self-reflection may have arrived early a while ago, even before 1980 for the especially large egos, but has arrived in force mostly in the last few years. We are now evidently beginning a smallish rush on the market, smallish in part because many of the books are self-published, smallish in another part because these are not the celebrity-status famous people or even the purported Beautiful People. A certain modesty is a great source of their attractions.

Milt Tambor’s Democratic Socialist Adventures surely takes the cake for modesty. It is all about him and it is not about him. This is a fellow who grows up within a Jewish-American world and never seems entirely comfortable about being there— no doubt because the institutions and their big shots have shifted sharply right during our political lifetimes, even when the community itself remains largely liberal. Tambor is forever, in these pages, reaching out beyond the limits of that world toward others, as he searches for a career equal to his talents. He is a “people skill” person who works with social service clients, with fellow workers of various kinds, and with allies, smoothing out tensions and searching for solutions in place of conflicts.

Tambor, as he explains, became early in his career a unity-builder between Jewish and minority communities in Detroit. He had a fine mentor: Saul Wellman, an erstwhile Communist dignitary of note as well as a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. Wellman had been doing the work of bringing people together for decades when young Milt came on the scene in Detroit. A more than willing protege, the younger man showed himself eager to build alliances, for his own reasons. Born in 1938 and raised in Miami and New York in a highly religious household, he was too old for the New Left and perhaps skeptical of imagined utopias. Besides, trained in social work was and assigned to community projects, not on the campus where the New Left action mostly took place.

You might almost say that Milt Tambor was born for DSA, or what became DSA.

On staff from 1965 at the UAW Retired Workers Center in Detroit, he was in a bargaining unit—a union within a union—for AFSCME. He soon set himself to organize various social work agencies as he prepared to go on to graduate school. He leaped into the labor movement’s own peace initiatives of the time, no easy matter when the AFL-CIO was led by super hawk George Meany and his circle of bureaucrats, enraged at peaceniks of any kind. Happily, the best of the old radicals were also against the war, almost as if the aging socialists of the 1930s-40s found a place to work together again. It was too little and too late, but meanwhile, Tambor had helped lead a strike of Detroit social workers, setting the pace for long term improvement of their collective situation.

The New American Movement formed in 1971 had a special appeal to him, bringing him into closer contact with such revered figures as Dorothy Healey. By the middle 1980s, he had become part of a labor delegation in support of Central American uprisings in Nicaragua and El Salvador, once again in sharp contrast to the AFL-CIO leadership. He also went back to graduate school and became a scholar of unions in social work, as well as a labor educator. With a pension, he took retirement and headed for an Atlanta retirement in 2001, eager for new political opportunities.

DSA had meanwhile emerged, joining two Left organizations and in a sense, bringing a sense of reconciliation between warring communist and anticommunist traditions. He was in the right place to push for Bernie Sanders, to build an Atlanta Metro DSA, and to secure the links with the labor movement that would make the movement a success in…. coalition building!

Nothing spectacular here but everything useful. Milt Tambor teaches us, especially but not only the young, how to be the Jimmy and Jenny Higgins of today and tomorrow.

Allen Young has a bigger story as well as a much, much bigger book, and I am not sure that even 450 pages tells it all. Or I am only griping because some of the high points—seem by this veteran observer of Allen Young’s work—do not seem to get the full treatment here.

What does get full treatment and what many readers (that is to say, fellow Red Diaper Babies in particular) will find stirring is Young’s detailed, beautifully written memoir of growing up in a Leftwing rural Jewish family in the Catskills. The intimate Jewishness, more tightly wound but also complicated by the hovering persecutions of McCarthyism. He also becomes gay in these years, and then it’s off to Columbia University where he becomes a journalistic star, editor of the campus Spectator.

Young tells us more, perhaps, than we need to know about his global travels after college, but he advances further in his journalism and his understanding of American imperialism. Heading back to Columbia and the journalism school, he finds his calling and is even writing a bit for the New York Times. After two spells in Brazil, his takes a job at the Washington Post.

He insists that it was the viewing of The Battle of Algiers, the famous film of Algerian revolt from French domination, that helped prompt him to leave a glorious mainstream future and head for the underground press. I have a different take. Young was headed for the biggest adventure of his life, and nothing could have likely kept him away.

To appreciate this point, one needs to grasp what the emergence of hundreds of local papers mostly during the later 1960s and early 1970s meant to newspaper innovation: staffed by amateurs, laid out in artistic versions unknown in the commercial press, sometimes with poems on the front page and wild cartoons inside, these papers broke every journalistic rule of the mainstream. By offering real news about the US invasion of Vietnam, news about the local resistance to the war that could not and would not be printed in the mainstream press, they gathered an audience of tens and hundreds of thousands thirsting for another kind of news and a fresh style of presentation. You could say the Web began here, although that would be giving the Web too much credit. These were truth telling papers, and LNS played a crucial role in spreading the reportage and insight from one page to another. Allen Young made it happen, and yet he seems to recall the reportage without the layout, a mystery to me.

This golden or reddish-golden moment could not last and did not. The New Left collapsed and LNS was doomed. Young was also by now a figure in Gay Liberation, turned off (to put it mildly) by restrictions in revolutionary Cuba, but also by the difficulties of the Gay Liberation Front, a very unique corner of the Movement that struggled to find its own place. Publishing his discoveries turned out to be somewhat of a disappointment. Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation (1972) came out at the right time to make a splash, although Young recalls that he failed to receive the royalty statements to find out the actual sales. The Gay Report (1979), a successor of sorts to the sensationally-selling Hite Report on current women's sexuality, never got the publicity it needed to go very far.

Much of the rest of the book concerns his life at “going back to the land” in several locations, ultimately Western Massachusetts. This is the section of Left, Gay and Green that seems overly long and overly detailed, as if personal life from the 1970s onward has overtaken the more outward eras. There is also something remarkably missing.

Young wrote in these years, as a local journalist in Athol, Massachusetts, hundreds of pages, at the very least, of local or regional community life and observation of the natural setting. Two little volumes collected and published locally deserve recuperating as a unique quality within Young’s life projects.

One can nevertheless appreciate the deep logic of Left, Gay and Green. Young wants to tell his story as a child of the Old Left, aka Jewish chicken farmers in the Catskills, the gay teenager who becomes not only a key journalist of the time but an important figure in the Gay Liberation movement, and then a back-to-the-land activist, with all the attendant problems of quasi-collective property and complex relationships. The story comes across as deeply humane, if more and more personal, less about politics and more about relationships in older age.

Spread the word