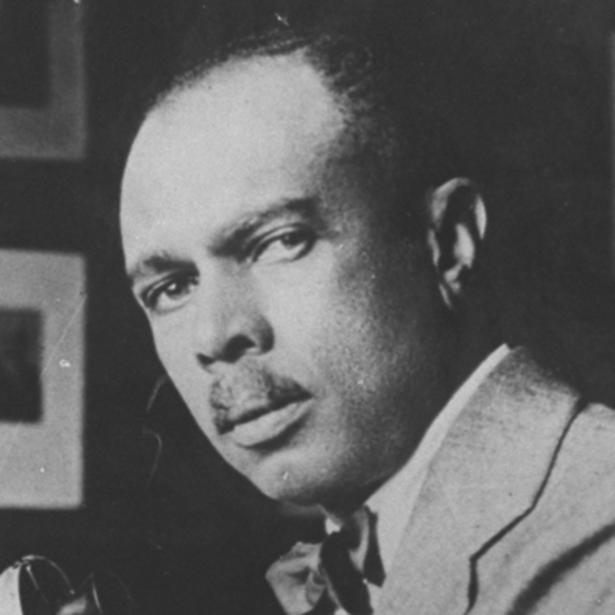

On Feb. 12, 1900, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing was performed by school children in Jacksonville, Fla. The song’s author was James Weldon Johnson, a renaissance man who was an educator, lawyer, novelist and activist. Johnson initially imagined Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing as a poem that would celebrate the birthday of Abraham Lincoln. But on the page it became something else.

Johnson’s lyrics told the story of Black life in terms that were epic, wrenching, and thunderous. It was in the same tradition as famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who, like most enslaved children, hadn’t had his birth date recorded. However, he’d chosen Feb. 14 as the day on which he would celebrate his birth, two days after Lincoln’s. Douglass’ classic, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, told the story of his journey from slavery to freedom with drama, passion, breathtaking emotion and stunning brilliance.

Johnson’s poem did something quite similar. He recalled his writing process: “A group of young men decided to hold on February 12th a celebration in honor of Lincoln’s birthday. I was put down for an address, which I began preparing, but I wanted to do something else also. My thoughts began buzzing round a central idea of writing a poem about Lincoln but I couldn’t net them. So I gave up the project as beyond me…My central idea, however, took on another form. I talked over with my brother the thought I had in mind and we planned to write a song to be sung as part of the exercises. We planned better still to have it sung by school children, a chorus of 500 voices.”

Johnson’s brother, Rosamond, was a composer. They were race men, hailing from Jacksonville, then the largest city in Florida with a population that was over 50 percent Black. It was a robust community, but one that lived under the thumb of a racially unjust system. In response to the rise of Jim Crow, Black Americans there, and across the nation, turned inward and organized. In the last 35 years of the 19th century more than 1,200 black newspapers were founded, and at the dawn of the 20th they served a vital function in Black life and letters. Black schools, from elementary to college were steadily opening and growing across the country. Black musicians were pursuing formal training, publishing their compositions and formalizing traditional folk. The range of musical conventions explored by Black musicians was expanding. Black literature was being published and activists described it as an important tool for racial uplift. Black people were writing themselves into history as scholars and biographers. Lift Ev’ry Voice was a part of that powerful energy.

The Johnson brothers left Jacksonville for New York. Unbeknowst to them, their song spread almost immediately, first across Florida and through the rest of the South. By the 1910s it was colloquially being described as the Negro anthem. And in 1919, though it rejected the idea of a separate “anthem” for African Americans, the NAACP declared Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing as its official song.

The song began with children, and in some ways its greatest legacy is in the impact it had upon children. When Carter G. Woodson formally declared Negro History Week in 1926, Lift Ev’ry Voice was enmeshed in the annual celebrations of Black history and culture in schools, and in the daily or weekly assemblies. Teachers and community leaders situated the song as a central feature of Black children’s lives.

For decades it was undeniably Black America’s most cherished song. One can hardly overestimate its impact. For example, during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, singing Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing was commonplace during the mass meetings that were held during the long months of the boycott lasting from Dec.5, 1955, to Dec. 20, 1956. And the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would quote the song in some of his most stirring speeches.

During the Black Power Movement, Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing was being sung with raised fists by people wearing afros and dashikis. Instead of calling it the Negro National Hymn, it began to be designated the Black National Anthem. In the 1970s, as Black mayors were elected in cities across the country, Lift Ev’ry Voice became a feature of inauguration ceremonies. To this day, it remains a signature element of Black formal occasions and celebrations.

A 2018 Washington Post article noted the significance of the song in society today. For example, at the 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama, the nation’s first Black president, civil rights leader Rev. Joseph Lowery started his benediction by reciting the third stanza of Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing. As the Black Lives Matter movement brought attention to the killing of unarmed Black men and women by police, the anthem was sung at protests and on the sidelines of NFL games when Colin Kaepernick was kneeling. And when musical icon Beyonce headlined Coachella in 2018, she sang Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing during her ode to historically Black colleges and universities.

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing is a reminder of the solidarity, commitment and community that African Americans forged to not merely survive in this nation, but to create beauty in the face of persistent injustice.

Imani Perry is the author of May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem, University of North Carolina Press, 2018 and the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University.

Spread the word