labor Athletes’ Racial Justice Protest Last Week Made History. But It Wasn’t the First Wildcat Strike in Pro Sports

On Wednesday last week, the Orlando Magic came out on the court and went through their usual warmups before their scheduled fifth playoff game with the Milwaukee Bucks at Disney World in Florida. But as the buzzer sounded to begin the game, the Bucks were still in the locker room. They were discussing how to respond to the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin — an hour from Milwaukee — on August 23. Several cops shot Blake in the back, paralyzing him. He remains in the hospital in critical condition.

Bucks guards George Hill and Sterling Brown, both African American, led the team meeting, where players crafted a statement, which they issued at a team press conference that evening, explaining why they refused to play.

“We are expected to play at a high level. Give maximum effort and hold each other accountable. We hold ourselves to that standard, and in this moment we are demanding the same from lawmakers and law enforcement,” Brown said.

Brown called on the Wisconsin legislature to reconvene for a special session called by Gov. Tony Evers, to take action and address police accountability, brutality and reform.

“And remember to vote on November 3,” Brown said.

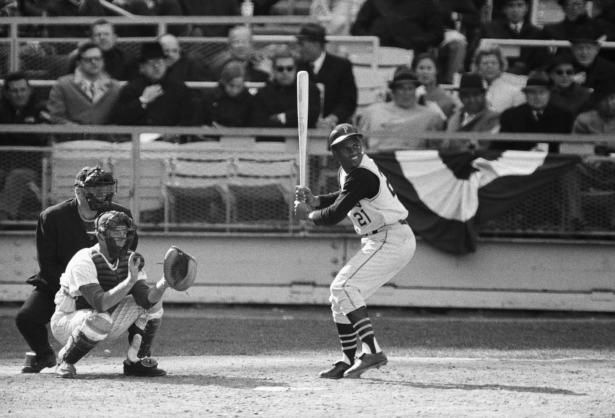

The Bucks’ defiance started a wave of similar actions by other NBA teams, then by baseball, tennis, soccer and other athletes. Some observers have called this the first “wildcat strike” in pro sports history. But that’s not entirely true. Pittsburgh Pirates All-Star outfielder Roberto Clemente led a similar action in 1968 that shut down major league baseball temporarily as well.

But this current upsurge of athlete activism is, indeed, remarkable. After months of negotiations between owners and players unions to reopen their seasons amid the COVID-19 pandemic, players voluntarily shut down the game out of frustration over racial injustice. Soon after the Bucks refused to play, the NBA and the players association announced that all three playoff games that had been scheduled for Wednesday would be postponed and rescheduled. The WNBA postponed three games scheduled for last Wednesday when players made it clear that they wouldn’t take the court.

Later that day, while waiting to host the Cincinnati Reds at Miller Park, the Milwaukee Brewers learned about the Bucks decision.

“As soon as we got in the locker room, we started having discussions as a team,” said Brewers outfielder Christian Yelich. “We had a team meeting shortly after and came to the decision” to cancel their game.

Since the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in June, the Brewers and other major league players began wearing jerseys in support of Black Lives Matter and racial equality. But after the shooting in Kenosha, the Brewers wanted to do more.

“We’ve been wearing these shirts throughout the year, but there comes a time where you have to live it, you have to step up,” Yelich told the Wisconsin State Journal. “That’s what you saw here today, us coming here collectively as a group and making a stand, making a statement for change, for making the world a better place, for equality, for doing the right thing and we did that as a group. It was a unanimous vote. Everyone was in favor of not playing, and sending a message and making a statement.”

“We wanted to be united with them in what [the Bucks] started,” explained Yelich, who is white. “Coming together for the city and just wanted to provide a better place, a better environment for everybody to be included, and change.”

“This is about us supporting our community and our country that’s in pain,” said another white Brewers outfielder, Ryan Braun. “I think that being that Kenosha is essentially an extension of Milwaukee, this one hits close to home and I think that it obviously impacted (the Bucks) deeply just as it has us.”

In New York, the Mets and Marlins initially took the field, but left after a planned 42-second moment of silence honoring Jackie Robinson’s retired uniform number. After the players left the field, all that remained was a Black Lives Matter shirt covering home plate.

After the Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Mookie Betts, the team’s only African American player, told his teammates that he was going to sit out last Wednesday’s game against the San Francisco Giants, the other 27 men in the clubhouse (including six Latino players) decided to join him in the protest. The Seattle Mariners and San Diego Padres did the same. Some players — including the Cubs’ Jason Heyward, the Cardinals Dexter Fowler and Jack Flaherty and the Rockies Matt Kemp — refused to play even though their teams took the field. By last Thursday, players had forced the cancellation of seven games.

Players for the Los Angeles Football Club and Real Salt Lake said they would not suit up for their Major League Soccer contest. Naomi Osaka, a top tennis star, announced she wouldn’t play in Thursday’s semifinals of the Western & Southern Open. “Before I’m an athlete, I am a Black woman,” she tweeted.

This week, NLF players discussed going on a wildcat strike during the season opening games season, scheduled for September 10. Faced with this player uprising over racial injustice, the NFL appeared to give its legal blessing for players to break their union contract and refuse to play those games.

Players took the lead, but some coaches and managers expressed their solidarity too. “It’s amazing to me why we keep loving this country and this country does not love us back,” said LA Clippers coach Doc Rivers, who went to Marquette University in Milwaukee. At a pre-game press conference last week, Bucks coach Mike Budenholzer, wearing a T-shirt that read “Coaches for Racial Justice,” discussed the shooting before taking any basketball-related questions. “Just like to send out my thoughts and prayers to Jacob Blake and his family, another young Black man shot by a police officer,” Budenholzer said. “We need to have change. We need to be better.”

“The Bucks led here,” Brewers manager Craig Counsell, wearing a Black Lives Matter shirt, said. “The NBA led here. But our players, they went first in Major League Baseball and I’m still very proud of them for that.”

Not The First Time

Pro athletes have gone on strike before over wages, pensions and working conditions, but these protests are about racial justice. It is no accident that Black players, who have talked about their own experiences being racially profiled by police officers, took the lead in organizing the walkouts. But just as public opinion among white Americans has become much more supportive of Black Lives Matters and skeptical of police treatment of people of color, white athletes have also been part of these walkouts against racial injustice and police abuse. A YouGov survey conducted last Friday found that 57 percent of Americans support the players who went on strike.

These strikes are the most dramatic expression of pro athletes’ growing anger over the condition of American democracy, but these feelings have been building ever since Donald Trump began running for president. Since then, we’ve witnessed a significant upsurge of protest by athletes in all the major sports. Best known is quarterback Colin Kaepernick, whose decision to kneel during the national anthem triggered attacks by Trump and his own blacklisting by NFL teams, even while inspiring athletes from high school to college to pro sports to emulate his actions. But there’s been a lot more.

In 2016, after Trump, then a presidential candidate, dismissed his vulgar “grab ‘em by the pussy” comment as just “locker room talk,” a dozen pro athletes –- from football, basketball, baseball, and soccer — denounced him. Washington Nationals pitcher Sean Doolittle tweeted at the time: “As an athlete, I’ve been in locker rooms my entire adult life and uh, that’s not locker room talk.”

Doolittle, LeBron James, Megan Rapinoe and many other athletes have used their celebrity platform to express their political views. They’ve opposed Trump’s exclusion of immigrants and asylum seekers, his racist comments after the neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville, and his harsh statements against athletes kneeling during the national anthem. Players on championship NFL, NBA and MLB teams, as well as the World Cup-winning women’s soccer team, have refused invitations to celebrate their victories with Trump at the White House.

These contemporary athletes, in turn, stand on the shoulders of sports trailblazers from earlier eras, like baseball players Jackie Robinson, Curt Flood, Jim Bouton, and Carlos Delgado, as well as boxer Muhammed Ali, track stars John Carlos and Tommie Smith, NFL players Jim Brown and Dave Meggyesy, tennis greats Billie Jean King and Arthur Ash, and NBA stars Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bill Walton, and Adonal Foyle.

These athletes saw themselves as part of broader movements for social justice, but they mostly acted on their own, by speaking out or by participating in civil rights, anti-war and feminist protest movements. But collective action by athletes on their own turf — as we’ve seen in the past week — is largely unprecedented.

The closest parallel to the current wave of athlete activism is major league baseball players’ response to the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968, led by the Pittsburgh Pirates All-Star outfielder Roberto Clemente. Clemente played for the Pirates his entire career, from 1954 to 1972, during the peak of civil rights activism. He closely followed the movement and identified with its struggles.

Coming from a more racially integrated island of Puerto Rico, he was shocked by the segregation he encountered in mainland America, especially during spring training in the Jim Crow South. He couldn’t stay in the same hotels or eat in the same restaurants as his white teammates. Clemente and other Black players were excluded from the Pirates’ annual spring golf tournament at a local country club, while their white teammates participated.

Clemente was a proud American (from 1958 to 1964 he served in the Marine Corps Reserves), Puerto Rican and Black man. He bristled over the racist way that sportswriters covered him. They called him “Bobby” or “Bob.” They made fun of his accent, quoted him in broken English and paid little attention to his powerful intellect and social conscience.

Clemente closely followed the civil rights movement and came to admire King, meeting the civil rights leader after he gave a speech at a university in Puerto Rico in February 1962. Later, King visited the Pirates All-Star right fielder at his farm on the outskirts of Carolina, Puerto Rico, and the two met several other times before King’s death, discussing racism, poverty, identity and politics.

Clemente frequently discussed social issues with his teammates and others. “Our conversations always stemmed around people from all walks of life being able to get along,” Pirates outfielder Al Oliver told David Maraniss, author of “Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero.”

“He had a problem with people who treated you differently because of where you were from, your nationality, your color; also poor people, how they were treated.”

Clemente talked “a lot about how being a Black Latin coming into baseball meant you had two strikes against you,” according to his wife Vera. “He wanted the Latino players to get their fair share of the money. He wanted them to be managers . . . to get respect.”

King was assassinated in Memphis on Thursday, April 4, 1968, during the last week of baseball’s spring training. His funeral was scheduled for Tuesday, April 9, the day after opening day.

Immediately, the NBA and NHL suspended their playoff games. Racetracks shut down for the weekend. The North American Soccer League called off games. But Major League Baseball waffled. After many players sat out the last few games of spring training to honor King, several owners insisted that Baseball Commissioner William Eckert, a retired Air Force general, penalize them for refusing to play. But Eckert was more concerned about the start of the regular season.

Rather than doing the obvious right thing, Eckert announced that each team could decide for itself whether it would play games scheduled for opening day and the day of King’s funeral. Some team owners, torn over what to do, approached their Black players to feel the pulse of their employees.

“If you have to ask Negro players, then we do not have a great country,” Clemente told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

King’s murder triggered rebellions in a number of cities with major league teams. Two teams — the Washington Senators and Cincinnati Reds — postponed their home openers because their stadiums were near the protests. But Houston Astros owner Roy Hoffheinz, a businessman and former Houston mayor, insisted that his team would play its opener against the Pirates — the third game scheduled for April 8.

“Our fans are counting on it,” explained Astros’ vice president Bill Giles. .

Under baseball rules, as the visiting team, the Pirates were required to play if the Astros wanted the game to go on. But veteran third baseman Maury Wills urged his teammates to refuse to play on opening day and the following day, when America would be watching or listening to King’s funeral. At the time, the Pirates had 11 Black players (six of them also Latino) on their roster, more than any other major league team.

After Clemente, the team leader, urged his teammates to support Wills’ idea, they took a vote. It was unanimous. Clemente and Dave Wickersham, a white pitcher, contacted Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown and asked him to postpone the season’s first two games. The two players wrote a public statement on behalf of their teammates: “We are doing this because we white and Black players respect what Dr. King has done for mankind.” Pirate players Donn Clendenon and Willie Stargell walked into the Astros’ locker room and persuaded the Black players to join the protest. The other players agreed and informed the Houston brass: They would not play the first two games, until after King was buried.

St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson and some of his teammates had the same idea. They met in first baseman Orlando Cepeda’s apartment and then told Cardinals management that they wouldn’t play on April 9, the opening day for most of the teams.

Players on other teams followed their lead. The Los Angeles Dodgers’ Walter O’Malley was the last owner to hold out, but when the Phillies players refused to take the field against the Dodgers, his hands were tied. Commissioner Eckert, his back against the wall, reluctantly moved all opening day games to April 10.

No sportswriter at the time described the players’ action as a strike. But that’s what it was — a two-day walk-out, not over salaries and pensions, but over social justice.

Clemente once said, “If you have the chance to make things better for people coming behind you and you don’t, you are wasting your time on earth.” He died in pursuit of that goal. On New Year’s Eve, 1972, he boarded a plane he had chartered in Puerto Rico to bring clothing, food and medical supplies to victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua. The plane crashed into the Atlantic Ocean at take-off. Clemente’s body was never found.

The following year, MLB waived its rule prohibiting players from being inducted into the Hall of Fame until at least five years after they retired. They held a special election and made an exception for Clemente. In 1973, he became the first Latino player to enter the Cooperstown shrine.

That same year, MLB established the annual Roberto Clemente Award, given to a player who “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team.”

This year’s award should go to the Milwaukee Brewers players who, like Clemente 52 years ago, led baseball’s strike for racial justice.

Peter Dreier is professor of Politics and the founding chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His books include Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century, The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame, and the forthcoming Baseball Rebels: The Reformers and Radicals Who Shook Up the Game and Changed America.

Spread the word