With nearly 60 years of professional cooking behind her, Anne Willan speaks with undeniable authority on all things culinary. Willan, who founded La Varenne Cooking School in Paris in 1975, has also written more than 30 books, many of them award-winners, and her “Look & Cook” series was a PBS success. She was inducted into the James Beard Foundation Awards’ Hall of Fame in 2013 and serves as an emeritus adviser for the Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts.

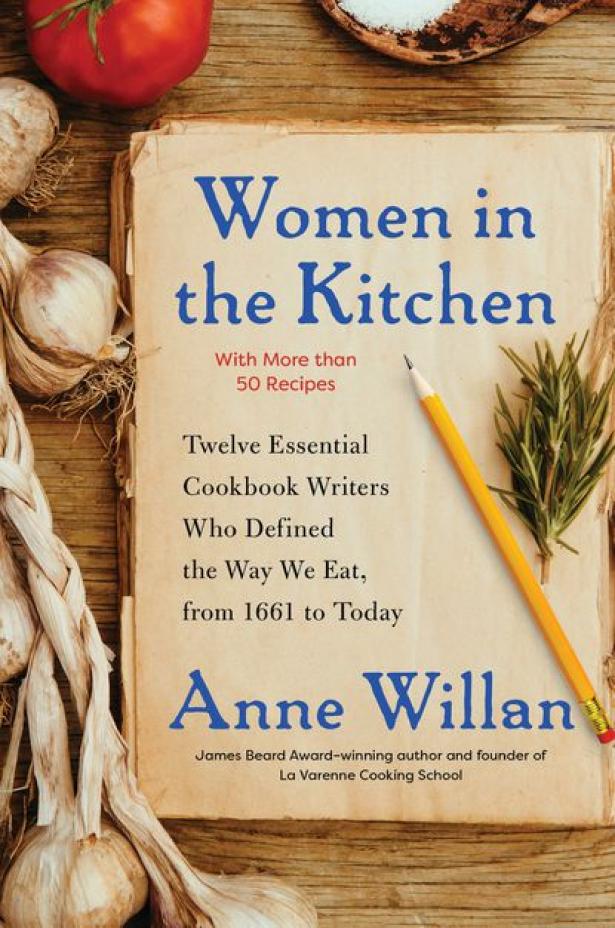

Now Willan has melded her passions for culinary history, writing and teaching into her fascinating new book, “Women in the Kitchen: Twelve Essential Cookbook Writers Who Defined the Way We Eat, from 1661 to Today” (Scribner, $28). Originally scheduled for release in May, the book was held back by publisher Scribner near the onset of the coronavirus shutdown, and now will be released Aug. 11. With more than 50 recipes, both in their original form and as recast by Willan for contemporary cooks, the book offers more than words to sustain its reader.

Willan’s research for the book was scrupulous, as an extensive bibliography shows; many of the works she cites would be hard for an average reader to obtain. Interestingly, some of those works could have justified their own inclusion: Isabella Beeton’s “The Book of Household Management,” Mary Randolph’s “The Virginia Housewife,” Reay Tannahill’s “Food in History” and Margaret Visser’s “Much Depends on Dinner.” But Willan wisely limited her choices to a simple dozen.

The book, arranged chronologically, spans more than 400 years of Western culinary history, with emphasis on British and American authors. Willan’s premise is that each author provided a base for those who succeeded her. Along the way, she describes the hardships these women endured as well as their successes.

It begins with a profile of Hannah Woolley, whose 1661 book, “The Ladies Directory,” was the first cookbook written in English by a woman. There were earlier cookbooks, Willan notes: The first cookbook, written in Latin, was published nearly 200 years earlier, she says. But unlike those earlier cookbooks, these books written by women, including Woolley, were meant to be read by the woman of the house who normally had to do the work of the kitchen herself. These readers hadn’t been served by earlier cookbooks, which presumed a fully staffed kitchen.

The earliest writers that Willan references put to rest the idea that earlier cooks didn’t know their way around the kitchen. Among the recipes Willan cites in Woolley’s chapter are instructions to make almond milk, which may surprise contemporary readers who think almond milk is a recent innovation.

Hannah Glasse (1708-1770) is up next, with her “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy.” Willan seems to have some affection for Glasse, as do most culinary historians I’ve encountered. In gossipy but kind detail, Willan describes Glasse’s life — a feckless husband, hard financial times including a bankruptcy, and more. Yet Glasse’s advice is still germane today, as Willan notes. “At Mrs. Glasse’s suggestion, I still use rosemary to flavor chocolate pudding,” Willan writes, “and a straggly little rosemary bush does surprisingly well on my balcony in north London.”

Amelia Simmons’ “American Cookery” follows Glasse. The author of the first cookbook written by an American using American ingredients, Simmons left no clues about her birth and death dates, Willan notes, but “she was a genuine pioneer” when the first edition was published in 1796. The Simmons chapter benefits from Willan’s deep understanding of culinary history. She describes the equipment that a cook of Simmons’ era would have at hand to cook over an open fire, from the three-legged skillets called spiders to Dutch ovens to spits for roasting. She notes that Simmons offers a variety of sturdy pastries to use to build a pie shell for meat pies for readers who didn’t have pie pans.

Again, Willan commends Simmons’ enduring wisdom: “Her advice on choosing cheese could hardly be bettered today: the inside should be yellow and flavored to your taste,” Willan says. “How right she is, always ask for a tasting.”

Many readers will be less familiar with succeeding early authors, including Maria Rundell (1745-1828), Lydia Child (1802-1880) and Sarah Rutledge (1782-1855). But most contemporary readers will recognize the 20th-century cookbook authors Fannie Farmer, Irma Rombauer, Julia Child, Edna Lewis, Marcella Hazan and Alice Waters. Willan’s summaries of these women’s contributions to American cookery are as intimate and charming as the earlier portraits are. Given her own long history in culinary circles, it’s not surprising that Willan knows many of these latter-day authors well. Whether in the spirit of full disclosure or a mild bit of name-dropping, for example, Willan points out that “Julia Child was a close friend (and a second grandmother to my own children).”

But Willan’s sense of the importance of all 12 of the women she writes about here is even-handedly warm and affectionate. Women cooks, Willan says in the last chapter, “enjoy passing on our knowledge to others.”

Toward that end, she contends that “the criteria for a successful cookbook by a woman has not changed since Hannah Woolley in 1661.” Among those criteria are recipes written clearly (and “preferably with a strong personal voice,” she says), and the need for writing that combines charm “and a clarion call to action in the kitchen.”

Spread the word