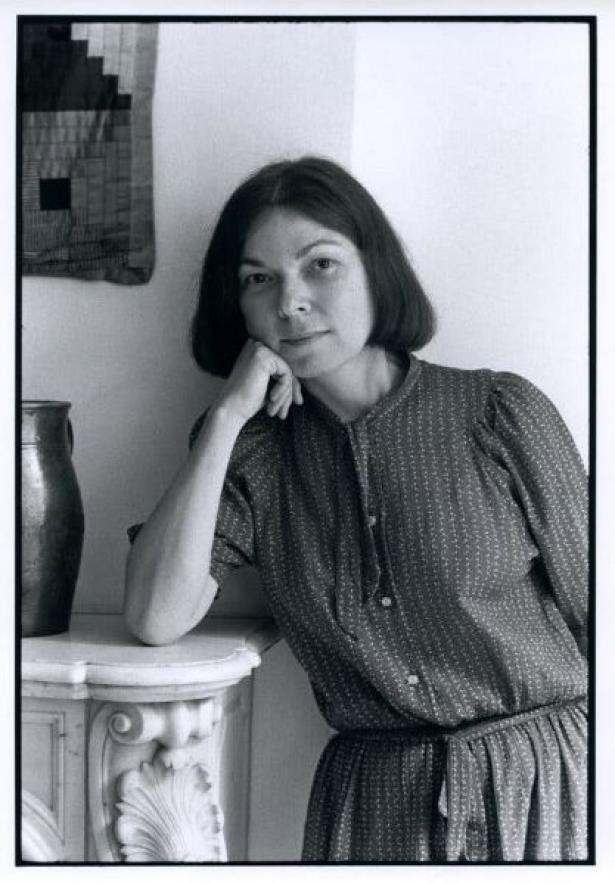

books Janet Malcolm, a Writer Who Emphasized the Messiness of Life With Slyness and Precision

Whenever I would begin to read anything by Janet Malcolm, my expectations were split in two: a soothing sense that it would be confidently and exactingly written, paired with an apprehension — an almost exquisite dread — of the startling truths it was bound to reveal.

Malcolm, the author and longtime staff writer for The New Yorker who died on Wednesday at 86, was preoccupied with doubleness, with divided selves that tried to keep one half hidden. Unlike the caricatured figure of the journalist she derided as “too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on,” she found duplicity less deplorable than inevitable.

Of course, some forms of deception are more malignant than others. There are the convicted killers in books like “The Journalist and the Murderer” and “Iphigenia in Forest Hills,” but what seemed to animate Malcolm most were the more ordinary manifestations of double lives — pretenses to selflessness that mask a deep selfishness; pretenses to certainty that mask an irreducible doubt. Saints and villains bored her. She was always looking for holes in those masks, for the weird and vulnerable human underneath.

That didn’t translate into her work being kind — a word that’s almost comically incommensurate with her acerbic narrative voice, the performative “I” she would insert into her essays and profiles. But it did fuel a curiosity for what she called “the small, unregarded motions of life.” Malcolm liked to include long quotations from her subjects, allowing them to reveal (or betray) themselves in their own words instead of pinning them down with a crude paraphrase. Her method of stitching together quotes from various conversations to shape those monologues got her into trouble when she was sued for libel by the psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson for her article about him in The New Yorker, which later became the book “In the Freud Archives.” In one passage (not among the five disputed ones), Masson recalled a conversation with Sigmund Freud’s daughter Anna, in which she said her father wouldn’t have wanted to be an analyst if he were alive today. “I swear those were her words,” Masson declared, before continuing: “No, wait. This is important. I said that to her.”

As the daughter of a psychiatrist herself, Malcolm was ever alert to inconsistencies and reversals, to text and to subtext, to the ways that we try to make ourselves intelligible to ourselves and to others. She was fascinated by relationships — Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes (“The Silent Woman”), Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas (“Two Lives”), the analyst and analysand (“Psychoanalysis”), not to mention the journalist and her subject. But she also refused the pretty delusion that our knowledge of one another could be anything but imperfect. “We must grope around for each other through a dense thicket of absent others,” she wrote in her book on psychoanalysis, whose subtitle is “The Impossible Profession.” “We cannot see each other plain.”

Malcolm recognized something tragic in this, but she also found it interesting — a word she occasionally used, but not in the way that too many writers use it, as filler or a crutch. “Interesting” for her was more active, and it wasn’t easy to obtain. “I have never found anything any artist has said about his work interesting,” she wrote in a profile of the artist David Salle. Anything so rehearsed and polished could never be. When she wrote that the German photographer Thomas Struth “radiates decency and straightforwardness,” you knew that something else was probably coming around the bend.

That profile of Struth eventually arrives at a moment of supreme discomfort: Struth makes a knowing reference to Proust and then, in response to Malcolm’s insistent pressure, admits he has never read any Proust. Struth, “a sophisticated and practiced subject of interviews,” later tried to explain himself, and Malcolm, for her part, “made reassuring noises,” but the snag in his otherwise impeccable presentation was too useful: “I knew and he knew that my picture was already on the way to the darkroom of journalistic opportunism.”

There was something funny in this, and Malcolm, who had written for her college’s humor magazine, didn’t limit her criticism to high art. She wrote about the pleasure she derived from watching Rachel Maddow, wearing the clothes of Eileen Fisher, reading Alexander McCall Smith. Writing about the “Gossip Girl” novels, Malcolm compared them favorably to the television adaptation (“the TV episodes are sluggish and crass — a move from Barneys to Kmart”) and praised “the Waughish achievement of these strange, complicated books.”

Malcolm was lauded for her writerly precision and control, but what truly set her apart was how she used those qualities not to elide but to accentuate complexity and ambivalence; she made you think you were reading one thing before sending you through a trapdoor. There’s an underbrush of wildness to her work, a sense that something strange is restlessly growing. One of her lodestars was Anton Chekhov, whose “bark of the prosaic,” she wrote in her book about him, “encases a story’s vital poetic core.”

As much as she understood the power of words, Malcolm was resolutely unsentimental about them. She wrote as if one could say something crushing about someone without leaving that person crushed. She may have been pessimistic about people ever fully knowing one another, but in another one of her swerves, she also suggested that it was through other people that we might begin to understand something about ourselves. This was why she kept starting and abandoning an autobiography, finding it too fiendishly difficult to invent herself without the energy she derived from others. As she wrote in 2010, “It isn’t easy to suddenly find oneself alone in the room.”

Spread the word