September 5 marks the 75th anniversary of a National Labor Relations Board election that took place at the China American Tobacco Company in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. It was the first NLRB victory in eastern North Carolina for the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural & Allied Workers of America (FTA-CIO), part of a campaign that would bring nearly 10,000 tobacco “leaf house” workers, most of them African-American women, into unions.

The FTA, like UE, practiced a brand of “them and us” unionism that stressed aggressive struggle, rank and file control, political independence and uniting all workers. Retired UE Local 150 leader Jim Wrenn writes in his introduction to “It Wasn’t Just Wages We Wanted, But Freedom,” a history of the campaign compiled by the Phoenix Historical Society, that:

These workers not only secured union contracts in over 30 some leaf houses which improved wages and working conditions, but these workers also engaged in mass voter registration and political action that challenged both the very profitable tobacco corporations of North Carolina as well as Jim Crow segregation and black disfranchisement.

Thanks to the work of the Phoenix Historical Society, this victory was commemorated in 2010 with a state historical marker, and in 2011 the city of Rocky Mount passed a resolution recognizing the importance of the China American election.

Jimmie Thorne, the current president of CAAMWU, the UE Local 150 chapter that represents workers at the Cummins Rocky Mount Engine Plant, has a personal connection to the history of the FTA: his grandmother Annie Mae Bynum worked at China American at time of the vote and his grandfather Wardell Bynum was the last president of FTA Local 10, the amalgamated FTA local that covered the eastern part of the state.

“Civil Rights Unionism” Comes to Eastern NC

The China American vote initiated a string of wins for Local 10 over the next two months of 1946 which brought FTA representation to two dozen more leaf houses throughout the region.

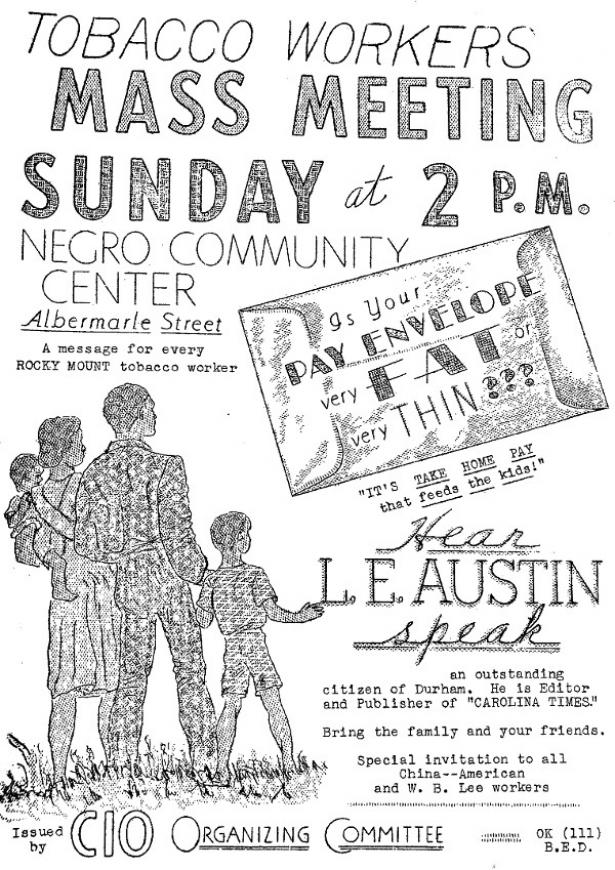

As was the case with FTA Local 22, which had successfully organized the huge R.J. Reynolds tobacco plant in Winston-Salem during World War II, Local 10’s organizing successes drew on the traditions and institutions of the black community. Mass meetings and rallies were held in black churches, and the Carolina Times, a Durham-based paper that was one of the leading voices of the state’s black freedom movement, endorsed the campaign.

A key tactic employed by Local 10 during negotiations for first contracts was short work stoppages. FTA organizer Ed McCrea remembered “A couple of times we’d just have a ten of fifteen minute stoppage, but that cost them a lot of money because that tobacco was burning up in drying kilns, and that’s where they couldn’t afford to have a stoppage.”

Thanks to this kind of aggressive struggle, workers got a ten-cent raise (approximately a 20-25 percent increase), and the companies agreed to stop using a loophole in the Fair Labor Standards Act which allowed them to avoid paying overtime during the fourteen-week season. Athenia Moses, who worked at the J.P. Taylor company in Goldboro, recalled in a 2007 interview that “We got a longer lunch break, a dining room, a first-aid room a 15-minute break. Why, when the union came in, we only eight hours a day. We even had some holidays.” Cornelius Simmons, who worked at Imperial Leaf in Greenville, remembered “Instead of sitting on a stack of tobacco to eat, we got a dining room. We got coolers rather than a nail keg with water in it.”

The establishment of the FTA in eastern North Carolina also challenged the dominant white power structure in the political arena. Local 10 set up a political action committee which registered members to vote and mobilized them to participate in elections. Simmons recalled that “After we got the union in there we started educating people. We got rid of a judge there who was real nasty. We changed a lot of the aldermen and got a different chief of police.” FTA’s Washington representative, Elizabeth Sasuly, was instrumental in getting severance pay, amounting to thousands of dollars, to black veterans in the region who had been unable to collect it due to obstruction from local white officials.

A Different South Was Possible

The FTA campaign in the eastern North Carolina leaf houses was part of “Operation Dixie,” a postwar effort by the CIO to organize the South. (UE did our part, starting with an election victory at a subsidiary of Stewart Warner in Winston-Salem the week prior to the China American vote.) Operation Dixie promised not only to raise low wages in the South, which threatened the gains CIO members had made in the North, but also to break the power of the anti-labor “Dixiecrats,” who ruled as a single party through much of the South and blocked pro-worker legislation in Congress.

Unfortunately, during this period the CIO largely abandoned its commitment to “them and us” unionism, and particularly its commitment to uniting all workers. Historian Robert Rodgers Korstad, who gave a talk about the FTA to the 2002 UE convention in North Carolina, explains in his 2003 book Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth Century South that:

CIO officials saw white textile workers as the key to organizing the South ... Assuming as they did that white textile workers were irredeemably racist and that they would respond only to the most cautious and narrowly defined appeals, Operation Dixie’s leaders took pains to play down the CIO’s strength in the black community, hired few black organizers, and avoided any linkage between unionization and civil rights.

The retreat from uniting all workers crippled Operation Dixie. The “them and us” unions that insisted on organizing black and white workers on the basis of equality, most prominently the FTA, were far more successful than the more conservative CIO unions. Another militant “them and us” union, the Farm Equipment Workers (FE), successfully organized the International Harvester plant in Louisville, Kentucky in 1946, building a strong biracial local that also challenged Jim Crow and the political establishment. Despite their successes in organizing the South, however, FE and FTA were sidelined by the CIO in “Operation Dixie” and eventually expelled, along with UE, in 1949 and 1950 respectively.

Korstad reports that “By any measure, FTA’s eastern North Carolina drive was among the most successful of Operation Dixie’s endeavors,” and it suggests how the history of the South in the second half of the 20th century could have been different had more CIO unions embraced the FTA’s commitment to uniting all workers and independent political action. Wrenn points out that the leaf house campaign is part of “what Robert Hinton has called the tradition of liberation politics in eastern North Carolina,” a tradition that “connects the history of Reconstruction in North Carolina with the current organizations that carry on that organizing tradition today,” including UE Local 150.

All quotes from FTA members and organizers used in this article are taken from Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism.

Spread the word