The Black Panther mystique is a powerful and complex one. Along with the Southern Civil Rights Movement, it transcended Black history to become American history, with all the gravitas that implies. As numerous events commemorating the party’s 55th anniversary approach in the coming days—including an unveiling ceremony for a bust of co-founder Huey Newton, an anniversary gathering in DeFremery Park, a tribute to the San Francisco chapter members at the Bayview Opera House, an art exhibit at the Joyce Gordon Gallery, and a remembrance of the Panthers’ singing group, The Lumpen—that mystique has again come to the fore.

Veteran Black Panthers say Hollywood and mainstream media portrayals of the party have often been misleading, focusing on a brief period of time when militant activism was at its peak, and not on the 65 community-oriented “survival programs” they say are the true measure of the party’s legacy and impact.

“All those films and movies we’ve seen, they always depict that particular origin period, with the berets and jackets, which only lasted up until mid-1970. After that, we were addressing the community,” said Dr. Saturu Ned, a former member of The Lumpen and educator at the Oakland Community Learning Center who’s currently a member of the Black Panther Party Legacy Alumni Network.

Fredrika Newton, Huey’s widow and the executive director of the Huey P. Newton Foundation, notes that the foundation published a book a few years ago documenting the survival programs.

“The most famous and most notable would be the free breakfasts the panthers offered to thousands of children in Oakland and other cities, providing basic nutrition for kids from poor families, long before the government took on this responsibility,” she said in an interview. “We knew that children could not learn if they were hungry, but we also had free clinics. We had free clothing. We had a service called SAFE (Seniors Against a Fearful Environment) where we would escort seniors to the bank, or, you know, to do their grocery shopping. We had a free ambulance program in North Carolina—Black people were dying because the ambulance wouldn’t even come and pick them up.”

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover once called the free breakfast program the “greatest internal threat to national security.” Ironically, after the panthers piloted the free meals through 28 national chapters, the idea was adopted in public schools and eventually evolved into the federally-funded WIC program.

“The Black Panther Party was doing what the government should’ve done,” Newton said. “We were providing these basic survival programs, as we called them, for the Black community and oppressed communities, when the government wasn’t doing it. The government refused to, so the community loved the Party. And that was not what you saw in the media. You didn’t see brothers feeding kids. you saw a picture of a brother who was looking menacing with a gun.”

The party’s members initially used armed patrols to police the police, but local governments, like Oakland, and eventually state lawmakers in Sacramento, responded by making it illegal to open-carry firearms, said Newton.

Newton has been tirelessly working to preserve and maintain the Black Panther’s legacy ever since the Newton Foundation’s formation back in the 1980s. A sore spot for her has been the absence of monuments, plaques, and art installations documenting and affirming the party’s historic contributions in Oakland.

“It was absolutely shameful that in the birthplace of the Black Panther Party, there was nothing,” she said. “There was nothing permanently placed in the city, and that was a shame. I’d rather not dwell on what should have been done, but to look forward to what we’re doing.”

A public monument to Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton

The Newton Foundation’s efforts have resulted in several recent initiatives to reclaim and preserve the Panther legacy in Oakland. The Foundation was essential in the effort to have the section of 9th Street in West Oakland where Huey Newton was murdered renamed Dr. Huey P. Newton Way. Fredrika Newton said that her organization drove the effort, obtaining necessary permits and approvals, and that the Oakland City Council played a very minor role in the process.

“The city didn’t name the street. I mean, the Huey Newton Foundation named that street and the City Council unanimously approved it. The city okayed the process. But we worked on it. We worked on that for a full year to get that street name changed.”

Another current Newton Foundation initiative is a bust of Huey Newton created by sculptor and former television news anchor Dana King, scheduled to be unveiled at 9th Street and Mandela Parkway on October 24. The public celebration will also feature a live performance by Grammy-winning Oakland native Fantastic Negrito, Afro stilt dancing by Prescott Street Theater, and onsite health screenings.

The Huey Newton bust, Fredrika Newton said, is “the first public permanent art installation in Oakland, in the birthplace of the Black Panther Party, that shows that the party ever existed here, much less was founded here. So this is historic in that way.”

This kind of recognition, she added, is necessary “so that children know that there were young men and women who were willing to lay down their lives for them, for their freedom, for their freedom from oppression, because they loved them so much.” Newton hopes that it gives the community that was raised through the Black Panther survival programs a way to “revel in that history that they were a part of.”

In creating Newton’s bust, King said her goal was to “bring him home and to bring him back to the community.” At first, she said it was hard for her to look past Huey’s physical appearance and, perhaps, his iconic persona and mystique. Fredrika Newton was a frequent visitor during the artistic process, King said. “She was here a lot in my studio and sharing stories and I mean, we’d laugh and then we’d cry.”

“My work incorporates deep research and I’ve read his poetry and the words he’s written, his dissertation, Revolutionary Suicide. It was all helpful in formulating a vision of a revolutionary and a leader, but Fredrika helped me to see who he was as a human being and a man, her husband, her friend.”

King hopes the bust, as a public art installation, will spur more community engagement with Huey Newton’s spirit.

Building revolutionary consciousness through music

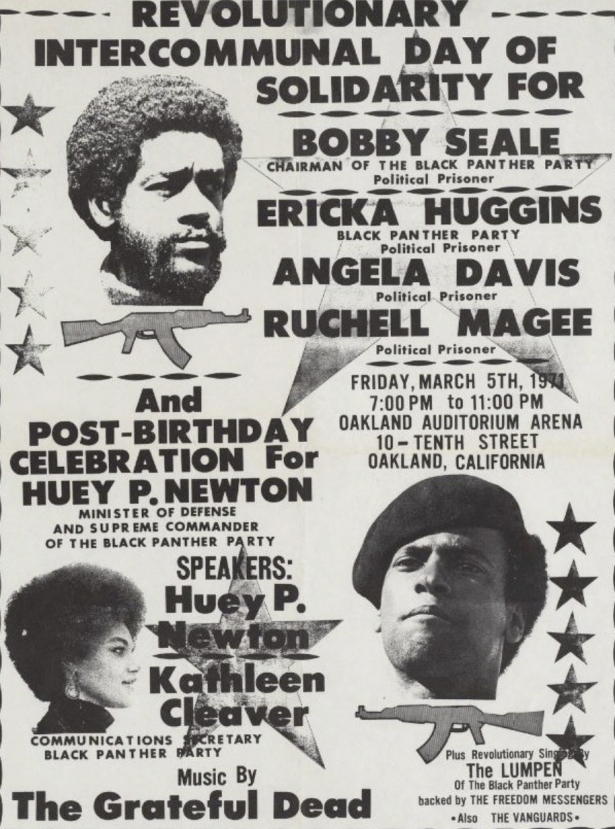

Another look into the Panthers’ cultural contributions will take place October 24 at Rocky’s Market in Brooklyn Basin, featuring a live discussion with three members of The Lumpen, emcee Kev Choice, and Marquise Melody. This is significant because The Lumpen, the Black Panthers’ revolutionary funk band, have not had a public event featuring more than two members in decades. The Lumpen—who took their name from the Marxist term lumpenproletariat, which means an underclass of people who aren’t conscious of their oppression or ability to collectively change the world— had an approach to Black music that intentionally employed social commentary and political themes. The Panthers viewed the lumpenproletariat, especially Black people, not as the “unconscious” masses but as the potential vanguard of a revolution in America.

Former Lumpen band member Ned recalls the group’s genesis. He worked at the Black Panther’s central headquarters at 1048 Peralta Street in West Oakland and would often sing songs he heard on the radio. One day, Emory Douglas, the party’s minister of culture came up with the idea of forming a band and pitched it to Ned. “People love music,” Ned said.

“Imagine if we could put some lyrics or some information where it becomes the message in the music, people hear it, they embrace it, they internalize it, and then they say, maybe I ought to start paying a little more attention,” Ned recalled Douglass saying. “Maybe I am going to read that newspaper. Maybe I am going to engage in helping in that program.”

In 1970, Ned—then known as James Mott—formed the Lumpen along with Bill Calhoun, Clark Bailey, and Michael Torrence. Their name was bestowed on them by Black Panther Party Chief of staff David Hilliard who had come to it after reading the revolutionary social philosophy of Franz Fanon, including The Wretched of the Earth.

“In America, we were talking about the dispossessed, the brothers and sisters and people in the community who hustle in every respect, and what I mean by that is that they even have great business setups which were hustles,” said Ned about the band’s name. “So those are the folks that were left, that fell from the cracks and everybody discounted—brilliant brothers and sisters who had never had the chance. So we represented that.”

Initially, The Lumpen performed alternative versions of popular hit funk and rock songs by the likes of James Brown and the Temptations, substituting socially-conscious lyrics before audiences at Panther rallies. But after Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale’s arrest and extradition to New Haven, Connecticut, and subsequent trial for allegedly ordering the murder of 19-year-old Alex Rackley, a member of the party, The Lumpen recorded their only officially-released record, the double-sided single Free Bobby Now b/w No More. Seale’s trial resulted in a hung jury and he was freed.

The single didn’t chart on the Billboard Hot 100, but it found success in Europe where it was embraced by the radical left and others sympathetic to the Panther cause.

“That helped with the birth and the development of the Black Panther movement in England and all over Europe,” said Ned. “It was because of hearing The Lumpen’s music at that time. And from that point on, we realized that the idea of reaching people [through music] was very important.”

An East Coast tour and a performance at San Quentin State Prison with Curtis Mayfield followed. The group later recorded a live album, which was never released; Ned suspects the masters were confiscated by the federal government as part of their COINTELPRO activities. The Lumpen disbanded in the early 1970s, but not before influencing everyone from Mayfield to the Chi-Lites, the O’Jays, Stevie Wonder and the Isley Brothers, who all incorporated deeper topics into their own music.

“I remember our band leader Bill Calhoun one day out of the blue challenged the Temptations and several groups. He said, why don’t you make some music that has a message in it?” Ned said.

In 1972, Mayfield scored the soundtrack to Superfly, which addressed drug addiction, absentee parenting, ghetto economics, and other street parables. The Chi-Lites’ (For God’s Sake) Give More Power to the People was performed live on Soul Train. Stevie Wonder told white America, You Haven’t Done Nothin’. The Isley Brothers released the single Fight the Power. And the O’Jays maintained, “got to give the people what they want.”

“They basically cloned the [Black Panthers’] 10-Point Program,” said Ned about the O’Jays’ hit song, which had lyrics calling for better housing, education, and more. “It was amazing.”

The Lumpen’s aesthetic extends to the Afrocentric era in hip-hop, when Public Enemy, X-Clan, Paris, Brand Nubian, Boogie Down Productions, Poor Righteous Teachers, and the Jungle Brothers put conscious ideologies ahead of freaky tales, dope fiend beats, drive-by salutations, and pimp manifestos. Other notable hip-hop artists directly influenced by the Panthers and The Lumpen include The Coup, 2Pac, and dead prez.

Hip Hop TV founder Shawn Granberry, a self-described “Panther cub” who’s also the promoter of the Oct. 24 event at Brooklyn Basin, said there are parallels between The Lumpen and conscious hip-hop group X Clan. According to Granberry, X Clan was a part of the activist organization Blackwatch just as The Lumpen were part of the Black Panther Party. “They were all rank-and-file members of the organizations, meaning that they actually went out and did work,” he said. The Lumpen did everything, from the free breakfast program to security patrols to distributing newspapers. “And they had to get up on the stage and sing, and then get off that stage and go right back to rank-and-file duties. The same thing was true with X Clan.”

The Lumpen’s history and their cultural influence were documented in San Francisco State University professor and author Rickey Vincent’s book Party Music, which also happens to be an album title by The Coup. Though still somewhat obscure, The Lumpen’s legend has spread far, reaching current artists who aspire to make music with a message, regardless of commercial sensibilities.

Emcee, composer, and Oakland Cultural Affairs Commissioner Kev Choice heard about The Lumen over the years but really only first became familiar with the group’s work when he was preparing his ensemble to perform at the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party five years ago. “We were hired to be the band for the gala at the Oakland Museum. Just in doing research about the music that impacted the Black Panther Party, I came across The Lumpen, seeing how they performed at the rallies and how they created songs that were calls for freeing of Bobby and Huey, and how they used their music to contribute to the movement of the Black Panther Party. That’s kind of what sparked my interest and understanding of them.”

Choice, who has collaborated with both the Oakland and San Francisco symphonies and released several albums independently with socially conscious lyrics and original production, said the Panthers’ impact is “instilled” in Oakland culture and artists of his generation. “This is the value of standing for the people, you know, that power to the people slogan is still very relevant. I feel like that’s very reflective of Bay Area culture, specifically Oakland culture, even to this day. It’s an art as a voice and not just something for profit.”

That same sense of community-orientated values informs people like Granberry, who notes that there are plans to make The Lumpen reunion an annual event, an awards show honoring socially-conscious artists across a range of disciplines, from music, to art, to poetry. “We want to really start highlighting those using their art to move consciousness and build revolution and open minds. So this has a long-term plan. In the future, it would be ‘The Lumpen Awards.’”

A shifting understanding of the Black Panthers, emphasizing the party’s rank and file

Fredrika Newton said the Huey P. Newton Foundation is just getting started. The upcoming initiative she describes is even more ambitious than the naming of Newton Way and the public art installation at Mandela Parkway. “We’re working with the National Park Service and the National Parks Conservation Association to create a Black Panther Party national historical park and monument here in Oakland. Barbara Lee is spearheading it,” she said.

Clearly, there is more to the Black Panther legacy than just a mystique. The continued relevance of the movement that started 55 years ago in Oakland is apparent in everything from 2018’s superhero movie Black Panther—a billion-dollar grossing film that opens in 1992 Oakland and hypothesizes a fictional Black-led African kingdom with superior technology—to the ongoing national debates over racial equity spearheaded by the Black Lives Matter movement and the reassessment of law enforcement in the wake of the George Floyd protests. Anyone paying close attention can see that the manifesto of the Movement 4 Black Lives organization, BLM’s policy wing, is closely patterned on the Panthers’ Ten-Point Program. The Oakland and Sacramento-based police reform organization Anti Police-Terror Project’s acronym, APTP, also stands for “all power to the people,” a subtle nod to the Panther slogan.

In Oakland, the Panther objective of impacting electoral politics, originally stated by Seale in 1972 during his historic run for mayor, not only laid the groundwork to the election of the city’s first African American mayor, Lionel Wilson, in 1977, but extends to the 2020 election of District 3 City Councilmember Carroll Fife, who ran on a platform of affordable housing and has been instrumental in advocating for the reallocation of the city’s budget from OPD to social services and arts and culture.

To people like Ned, the alignment of contemporary social justice activism with initiatives conceived decades ago is a validation of the Panthers’ struggle and their foresight. “We said from the heart that we got to create concrete concepts that are going to change the real dynamics of the community,” said Ned. “So I think people are really looking at that . How was that done? What was the thought process? What drove you guys to stay the course and how can we utilize that today?”

In 2021, as the Panthers’ long shadow continues to loom over everything from hip-hop to activism to equity-based approaches to economics, the environment, public safety, health, and education, public opinion regarding the organization has also evolved. Over the past five or so years, the mainstream, media-influenced view of the Panthers has started to shift, revealing subtler aspects of the Panther legacy. In 2016, documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson’s Vanguard of the Revolution and the Oakland Museum of California’s landmark BPP 50th anniversary exhibit, All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50, both emphasized the experiences and stories of the rank-and-file Party members. Earlier this year, the women of the Party, who at one time comprised 77% of its members, according to Newton, were honored in a mural painted on a West Oakland home, attracting widespread media coverage.

The reason for the shift in perception?

“I think it’s timing,” says Fredrika Newton. “Technology’s really helped to show the atrocities that have happened to Black people in real time, over the last two years when we were in our homes and couldn’t escape. Seeing Black people being brutalized and killed by the police. And so, it brought [police brutality and racism] up close and personal in people’s homes, in a way that hadn’t happened before.”

With the passage of time there’s been a gradual recognition,” said Newton. “And now it’s just been in your face that there was a difference in what the media portrayed the Black Panther Party to do versus what we actually did do.”

Writer, editor, and photographer Eric Arnold cut his teeth covering the Bay Area’s uniquely independent hip-hop scene, from Hieroglyphics to hyphy. He has written for national outlets from Vibe to the Source to Okay Player to Billboard to Making Contact, as well as local outlets including the East Bay Express, SF Bay Guardian, SF Weekly, SF Chronicle, KQED Arts, Oakland Local, and Oakulture. In 2018, he co-curated the Oakland Museum of California’s groundbreaking “Respect: Hip Hop Style and Wisdom” exhibit. In addition to hip-hop, he has covered diverse topics including dance, film, spoken word, world music, street art, gang injunctions, environmental equity, social justice, and media policy. He is currently based in Oakland, California.

The Oaklandside's nonprofit newsroom is committed to serving our readers with in-depth local reporting and resources to keep our community informed and better able to engage in the civiclife of our beautiful city.

If you find our work valuable we hope you will support us, and keep our journalism free for all, by becoming a monthly member.

The Oaklandside is part of Cityside, a 501c3 nonprofit news organization (EIN 84-3448887). Donations can made at:

https://checkout.fundjournalism.org/memberform?org_id=oakland&campaign=…

Spread the word