“It’s time for a new Reconstruction story — a story that will help us better understand how we got here. A story where the central characters are the Black people who fought to liberate themselves, who gained political power despite every attempt at violent suppression.” —Kidada E. Williams

The Radical Promise of Reconstruction

Reconstruction was the era in which 4 million newly emancipated people seized their freedom (to borrow from the evocative title of Dr. Kidada Williams’ fantastic podcast, Seizing Freedom). In thousands of acts of creation, both individual and collective, humble and grand, formerly enslaved people and their allies sought to build the world anew. In the words of Frederick Douglass, the era offered “nothing less than a radical revolution.”

Reconstruction has much to teach us about why our society looks the way it does today — and how it might be positively transformed. However, in the first-ever comprehensive review of state standards on Reconstruction, the Zinn Education Project found that most states do a dreadful job defining the era or outlining for educators its crucial themes. Standards mostly erase the role of Black people striving to execute their vision of freedom, instead favoring a top-down emphasis on government and the role of white people. Black people are included in state standards, but more often as objects than subjects. Even more troubling, many of the standards echo the racist and discredited “Dunning School,” which saw Reconstruction as an era of Black misrule, orchestrated by “scalawags” and “carpetbaggers.” More than a dozen states direct students to consider whether Reconstruction was a “failure” or a “success,” but neglect to emphasize the role played by white supremacy — in both the North and South — and the efforts of white people to crush the promise of Reconstruction. And state standards mostly fail to link past and present, or suggest how the study of Reconstruction can help young people think more clearly about their world today. Rather than offering students an entry point into a thrilling chapter in the long history of the Black freedom struggle — a struggle that continues — state standards offer an incoherent, unhelpful tangle of dates and topics.

There are exceptions — Hawaii’s standards frame Reconstruction as a critical era of “promise” in U.S. history and Massachusetts’ standards are notable for naming white supremacy — but they are few and far between.

The scope and speed of change during Reconstruction is hard to overstate. For the formerly enslaved, practically every sector of life was up for revision and reinvention. In his wonderful book, Black Power USA, Lerone Bennett Jr. describes a scene in which “76 Black men, many of them former slaves, and 48 white men, some of them former slaveowners” gathered in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1868 to draft a new state constitution. Bennett writes: “A mood, frightening in its intensity, oozes up from the restless Black people . . . What shall we call this mood? Defiance? Desperation? Joy? The mood is made of all these, but most of all it is made of hope.”

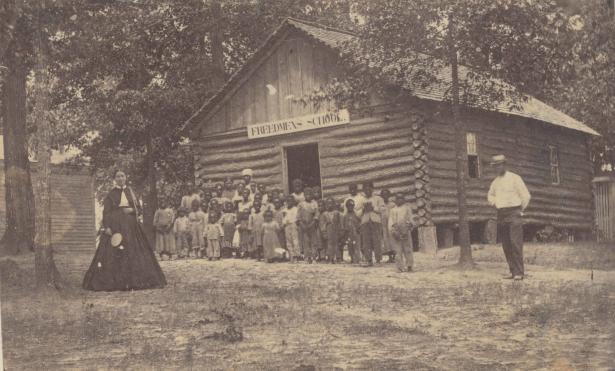

That hope fueled action. Even before abolition was affirmed by the law of the land, Black people got to work making freedom manifest. They built churches, mutual aid organizations — and hundreds of schools. The powerful drive toward literacy and education was, according to historian James Anderson, “an expression of freedom.” As the New Orleans Black Republican explained in 1865, “Freedom and school books and newspapers go hand in hand.” Formerly enslaved people reunited with stolen family cleaved by slavery, formalized marriages, and established households on their own terms. They negotiated for control over their own labor, sought access to land, and advocated for the right to vote and serve on juries, and for state-funded public education. They held conventions like the one so poignantly described by Bennett Jr., and ran for and held political office at every level of government. And they joined the political coalition that enacted the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, fundamentally changing the nature of U.S. citizenship and government.

Reconstruction at School

The powerfully relevant example offered to young people by the fight for abolition, and full freedom afterward, convinced the Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, to create the Teach Reconstruction campaign. That campaign seeks to address the dearth of curricular and pedagogical attention to Reconstruction compared to other formative moments in U.S. history (the Civil War or the Civil Rights Movement, for example). The report, Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction, grows out of this campaign. The precise relationship between state standards and teachers’ classroom practice is hard to pin down. But state standards directly influence the content of social studies textbooks, which anchor many teachers’ curricula. The current standards do not make it impossible, but they certainly make it less likely, that educators will teach a robust, accurate, and relevant version of Reconstruction — a version that might serve as a “usable past” for young people today.

The authors of the Zinn Education Project report argue, “The foundational premise of any set of teaching and learning standards for the Reconstruction era should be Black people’s agency, highlighting both what Black people did (to end slavery, engage in politics, build institutions, etc.) and what goals, beliefs, and motivations undergirded those actions.” But with a few exceptions, state standards overwhelmingly emphasize a white-dominated, top-down history with little emphasis on ordinary Black people. In Florida, for example, the standards focus on the actions of government and on white people, including Southern whites and the Ku Klux Klan:

Explain and evaluate the policies, practices, and consequences of Reconstruction (presidential and congressional reconstruction, Johnson’s impeachment, Civil Rights Act of 1866, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, opposition of Southern whites to Reconstruction, accomplishments and failures of Radical Reconstruction, presidential election of 1876, end of Reconstruction, rise of Jim Crow laws, rise of Ku Klux Klan).

But what do the standards say about the role of Black people? They are silent on the 44 percent of Florida’s population who were enslaved in 1860 and on what these newly emancipated people wanted, believed, and did during Reconstruction. Alabama advises its teachers to: “Define the roles of individuals such as carpetbaggers and organizations such as the KKK on the social and political structures of Alabama during Reconstruction.” Like in Florida, the actors of Reconstruction are white — Northerners who moved into the South (“carpetbaggers”) and violent opponents of racial equality (members of the KKK). As the authors of the Zinn Education Project report point out, “Black people are not actors in this narrative, Reconstruction happens to them, they do not shape it or participate in it.” Winning the award for the most abstract framing of Reconstruction, completely devoid of the people who actually make history, are the standards from a school district in Arizona directing students to learn that “Reconstruction was a period of conflict between the branches of government and the states.”

This Arizona district’s fuzzy framing is not an outlier. The report found that most standards fail to provide clear and consistent definitions of Reconstruction — if they mention the era at all. Alabama’s state curriculum guide defines Reconstruction as: “The period after the Civil War when the South was rebuilt; also the federal program to rebuild it” — a description unlikely to pique students’ — or anyone’s — interest. There is no human agency in the equation; the “South was rebuilt” but the closest we come to finding out who rebuilt it (never mind for whom) is the vague “federal program.” Also, these standards offer no explanation of what is being rebuilt — the war-torn physical landscape? Or cultural, political, and economic institutions?

In Indiana, standards direct students to understand the “political controversies surrounding this time such as Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, the Black Codes, and the Compromise of 1877.” What is the connective tissue that holds this mashup together? Are educators expected to inductively discover the meaning of Reconstruction through this list of “political controversies”? In many states, Reconstruction only appears on a list of topics or themes teachers should address for a particular time span; in Maine, Reconstruction doesn’t even merit that much space. Maine’s standards define the period 1844–1877 as “Regional tensions and the Civil War.” Connecticut too leaves out Reconstruction in its list of themes like Westward Expansion, Industrialization, and the Rise of Organized Labor. It is no wonder that, as the report states, “Most people in the United States know very little about Reconstruction. What they do know is often untrue.”

That Reconstruction is the subject of significant miseducation is borne out by several states’ standards that reveal traces of the Dunning School, an early 20th century historical interpretation of the era named after the Columbia University historian William Archibald Dunning, whose racist narrative reigned for half a century. In Dunning’s words, Reconstruction was the “scandalous misrule of the carpet baggers and negroes,” a “social and political system in which all the forces that made for civilization were dominated by a mass of barbarous freedmen.” The most obvious example of Dunning’s lasting influence is the frequency with which the words “carpetbagger” and “scalawag” show up in state standards. Alabama, Oklahoma, and Tennessee standards exhort educators to “explain the role carpetbaggers and scalawags played during Reconstruction.” Standards treat these terms as if they are neutral, and not the political rhetoric of white supremacists intent on reversing gains toward racial equality. In Texas, one standard asks students to “explain the economic, political, and social problems during Reconstruction . . .” There is no similar standard calling for explanations of how Reconstruction resulted in the expansion of democracy, education, and rights. Texas requires its children to learn about Reconstruction as an era of problems, not solutions.

What Happened to Reconstruction?

A more subtle example of the influence of the Dunning School can be found in the “successes and failures of Reconstruction” framing that shows up in dozens of standards across the nation. Arkansas’s standards call for students to “Evaluate successes and failures of Reconstruction,” while Tennessee’s ask them to “Assess the successes and failures of Reconstruction as they relate to African Americans.” In Idaho, children should be able to “Develop a claim and counterclaim debating whether Reconstruction was a success or failure and provide evidence highlighting the strengths and limitations of both arguments.” Given the Dunning School’s narrative of Reconstruction as an era of “scandalous misrule” — i.e., a “failure” — one can imagine that the writers of these state standards see the inclusion of “successes” as a kind of balance, a framing that allows for arguments on “both sides.” But both sides of a fake coin are equally counterfeit.

The most significant problem with the successes and failures framing is that it masks the truth about Reconstruction’s demise. The economic, political, and social gains made by the formerly enslaved during the 1860s and 1870s were swiftly and violently reversed. White vigilante groups and the Democratic Party waged a deliberate campaign of terror to restore an antebellum social order of white social, political, and economic supremacy. The Republican Party, dominated by Northern economic elites, reneged on promises to freedpeople — and the larger promise of multiracial democracy — by returning to “business as usual.” No, Reconstruction did not “fail” — a passive construction that suggests an inherent flaw. Reconstruction was destroyed, and its destruction was reinforced in laws, institutions, and social customs that would preclude multiracial democracy well into the 20th century. White supremacy’s fingerprints are all over the crime scene, but only a single state — Massachusetts — includes the term in its standards.

This reflects a larger pattern the Zinn Education Project report surfaced: Standards rarely name or contend with white supremacy or white terror. Outrageously, Georgia’s “Standards of Excellence” instruct teachers to “Compare and contrast the goals and outcomes of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the Ku Klux Klan.” By placing white supremacist vigilantes intent on violently subordinating Black people side-by-side with the federal agency tasked with supporting them, the Georgia standards suggest the two organizations are comparable and on equal footing. This is a grotesque version of the “let’s look at both sides” approach found in so much social studies curriculum. In Ohio, the standards say, “Following Reconstruction, old political and social structures reemerged and racial discrimination was institutionalized.” The passive construction of this standard manages to hide violence, and to name neither white perpetrators nor Black victims, in the reemergence of “old political and social structures.” South Carolina’s standards claim that the end of Reconstruction was the result of a “compromise to demilitarize the southern states.” A compromise between whom? Certainly not the Black people left most vulnerable to the violence of white mobs unleashed with the withdrawal of federal troops.

The successes/failures framing also sidesteps two critical understandings students should bring to Reconstruction and, really, to all history. First, though the Dunning School called white supremacist fables “history” and its political projects “common sense,” there is no universal metric of success. The extension of the franchise to Black men, for example, was understood differently depending on one’s social position — race, class, gender — and politics. To evaluate successes and failures one must also ask, “for whom?” and “toward what end?”

Second, Reconstruction was an era defined by a series of economic, political, and social struggles — many of which continue to this day. Asking children to check the “success” or “failure” box is to force them to ignore the dynamism of history, to trap in amber what is still very much alive and still under way. The struggle for voting rights did not “succeed” with the 15th Amendment, “fail” with the rise of Jim Crow, or finally “succeed” with the Voting Rights Act of 1965; that struggle continues today. The struggle for land did not “succeed” with the allocation of Confederate land to freedpeople (Field Order No. 15), “fail” with its revocation by President Johnson a year later, “fail” again with the rise of redlining, and ultimately “succeed” with the Housing Act of 1968; that struggle continues today.

Reconstruction Today

History teachers are fond of talking about history as “relevant” to the modern moment; we want our students to understand that the past offers explanations of our origins, examples to be followed or avoided, models and inspiration for action today. But Reconstruction is more than relevant. It is ongoing. It extends into the modern racial justice movement, which demands that the “badges and incidences of slavery” be finally eradicated, from housing to health care, education to employment, policing to prisons. It extends into the efforts of voting rights activists seeking to dismantle the latest round of racist barriers to the franchise. It extends into demands that Confederate monuments be removed from public spaces and the chants of “You will not replace us!” by white nationalists rallying to keep them intact. Reconstruction was alive in the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Though the Confederate flag-draped insurrectionists failed to overturn the 2020 election results, their leaders’ efforts to undermine democracy continue.

One front in this effort can be seen in the more than two dozen states where rightwing politicians have introduced — and 11 states have enacted — bills or rules to restrict what teachers can say in their classrooms about race, racism, and other “controversial topics.” Teachers across the country — in Missouri, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Alabama, Arizona — told the Zinn Education Project that they feared these laws would restrict teaching about Reconstruction. A teacher in Iowa explained that the law in his state was having a “chilling effect on current teachers who need to teach about white supremacy and racism in order to do justice to the topic.”

A middle school history teacher in Louisiana told the Zinn Education Project, “It’s impossible to understand the rest of the history of the United States without an understanding of Reconstruction.” Indeed. Which is why it is critical that educators and allies across the country resist the current spate of McCarthy-like tactics. As the Zinn Education Project’s Reconstruction report attests, the state standards guiding history educators’ practice were insufficient even before school board meetings became a favorite forum for the right wing’s white grievance politics. Now, these standards are likely to get a closer look and to become another target of the campaign to censor the past. We must be ready to answer those attacks with a commitment to Reconstruction’s importance and the belief that history is not a bargaining chip. Reconstruction was the breathtakingly ambitious effort led by formerly enslaved people to eradicate a brutal and entrenched form of racist exploitation, and to build an entirely new society. In countless ways, that effort continues today. Reconstruction was, to borrow the words of Langston Hughes, the struggle to create “the land that has never been yet.” Reconstruction history — taught well — conveys not just what it was, but what it is, and offers students a role as participants in determining its future.

***

How We Should Teach Reconstruction:

The Zinn Education Project’s 10 Reconstruction Standards

The Zinn Education Project created and rooted our assessment of the state of Reconstruction education in the set of teaching and learning standards below. These standards were developed in collaboration with scholars and teachers.

The foundational premise of any set of teaching and learning standards for the Reconstruction era should be Black people’s agency, highlighting both what Black people did (to end slavery, engage in politics, build institutions, etc.) and what goals, beliefs, and motivations undergirded those actions. Descriptions of the violent backlash to Reconstruction should emphasize how white supremacist ideology drove the effort to overturn multiracial democracy in the South and shaped the political and economic development of the entire nation after the Civil War.

In schools throughout the United States, students should:

1. Examine what Reconstruction reveals about the meaning of freedom to Black people.

For example, lessons should examine how formerly enslaved people exercised autonomy over self, family/kin, community; organized and mobilized around issues of land, labor, production, education, and worship; cultivated joy and creativity; sought the civil and political rights most critical to their freedom; and conceived of that freedom through traditions of resistance formed long before emancipation.

2. Know that control of land was of paramount importance to formerly enslaved people during Reconstruction, but widespread land reform and Black landownership was systematically denied by federal and state governments.

For example, students should examine the Savannah Colloquy and Special Field Order No. 15, the Homestead Act v. Southern Homestead Act, President Johnson’s “restoration” of land to Confederates, and the rise of state and local policies designed to immiserate and confine Black people.

3. Know that the struggle by freedpeople to control their own labor during Reconstruction was a source of conflict between freedpeople and economic elites, North and South.

For example, students should examine the Freedmen’s Bureau’s role in overseeing labor contracts between the formerly enslaved and white landowners, Northern elites’ desire to restore the Southern plantation economy, and the racial politics of labor organizing, North and South.

4. Examine the Freedmen’s Bureau to determine what it reveals about the needs and desires of freedpeople at the end of the war, its successes and failures, and how and why it was dismantled.

For example, students should examine how the Freedmen’s Bureau — formally named the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands — worked to secure food and medical care for freedpeople, reunite loved ones separated in slavery, establish school systems, redistribute land; how white resistance to these aims and lack of funding impeded and overwhelmed its efforts; how white supremacists across regions targeted agents and pressured Congress to disband it.

5. Examine the modes of mass political participation of Black people during Reconstruction.

For example, students should investigate the Union Leagues, state constitutional and political conventions, voter registration and education campaigns, press outlets, self-defense and self-help organizations, and schools and churches.

6. Examine the advances for democracy and racial justice made due to the mass political participation by Black people during Reconstruction.

For example, students can investigate African American lawmakers and officeholders elected at all levels of government; passage of laws at the state level providing tax-funded public schools, fair labor contracts, universal male suffrage, the right to divorce, the right of Black people to hold office and serve on juries; support for and mobilization around Radical Republican efforts in Congress: Reconstruction Acts, Enforcement Acts, and the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

7. Know that white supremacists used terrorism and fraud to stall and reverse many of the significant advances made by Black people and their allies during Reconstruction, and shaped the politics, policies, and outcomes of the era.

For example, students should analyze different manifestations of racism in the Democratic and Republican parties, South and North, and in labor relations, South and North; how Black institutions and symbols of Black achievement were undermined with racist terror and violence; how violence (vigilantes, the Ku Klux Klan) functioned to achieve the white supremacist goals of the Southern Democratic Party and the rise of Jim Crow apartheid.

8. Learn how elites in the North and the Republican Party prioritized their own economic interests by retracting support for the federal government’s role in protecting the advances made by Black people and their allies during Reconstruction.

For example, students should analyze how Northern industrialists successfully extended their dominance into the South — including Northern railroads acquiring massive tracts of public land — which shaped their interest in maintaining status quo labor relations; and how the 1873 economic depression fueled labor activism and strikes, incentivizing Northern industrialists to join Southern “redeemers” in a politics rooted in the fear of a revolt from below.

9. Investigate the legacy of the crushing of Reconstruction’s promise in their own lives and the current historical moment.

For example, students should examine the United States’ failure to award reparations for slavery; the failure of the federal government to endorse and support the most transformative promises of Reconstruction: land reform, universal suffrage, and civil rights; and the persistence of Jim Crow racism at all levels of society (policing and prisons, disparities in health, wealth, housing, employment, and education).

10. Investigate positive legacies of the Reconstruction era in their own lives and the current historical moment.

For example, students should examine Reconstruction-era schools and churches; the rich tradition of Black politics; the 14th and 15th Amendments, which continue to be the basis for expansion of and defense of civil rights; Reconstruction as a model of grassroots activism and participatory, multiracial democracy.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (ursula@rethinkingschools.org) has taught high school social studies since 2000. She is on the editorial board of Rethinking Schools and is an organizer and writer with the Zinn Education Project.

Spread the word