Last fall in Southlake, Texas, a Carroll Independent School District (ISD) school administrator provided baffling guidance to a group of teachers following the passage of a state law banning the teaching of critical race theory (CRT). Heard in a secret recording, she tells the teachers to present multiple viewpoints on contentious subjects and specifically names the Holocaust.

“Make sure that if you have a book on the Holocaust that you have one that has an opposing…that has other perspectives,” the administrator says.

There are audible gasps. One teacher asks, “How do you oppose the Holocaust?”

An author of the Texas bill subsequently argued that school administrators misrepresented what is in the new law. Regardless, the law’s language—and that of other bills introduced across the nation—is restrictive and can hinder teachers from effectively teaching lessons on race, history and current events.

Some consider Southlake “ground zero” for today’s discourse about how race and history are taught.

During the summer of 2020, Carroll ISD officials created a cultural competency action plan to address racism and improve culture at its schools. Parents and an organized political group opposed the plan, citing concerns about divisiveness and indoctrination. Around the same time, political figures demonized critical race theory—a strategy in response to the summer’s racial reckoning. And it gave opponents of Carroll ISD’s DEI plans new language to explain their irritation.

Since then, campaigns to influence school board elections, ban books on race, prohibit teaching uncomfortable histories and disrupt attempts to adopt DEI programs have been successful across the country.

Just five miles southwest of Southlake, James Whitfield, Ed.D., lost his job as a principal—the first Black principal—at Colleyville Heritage High School. He worked to create a more inclusive school environment while a storm was brewing up the road.

“We know over the course of history, anytime there’s progress made, there’s going to be a level of backlash that comes into play,” Whitfield says. “[Groups have] been disrupting public schools for a long time, just with other issues. Now, it’s just CRT. So this is what they came with to disrupt this movement towards unity and a true reckoning and healing in that community.”

An honest retelling of United States history includes events and experiences of all people who shaped it. To challenge the traditional narrative—one steeped in white supremacy and American exceptionalism—is to challenge power. Hence, the agitation we’re witnessing around what teachers teach and how.

But teachers are using this moment to have honest, critical class discussions. While caught in the middle of hostile political discourse, they recognize this as an effort to simply uphold the status quo. And we know what’s at stake when we uphold the status quo.

What’s at Stake?

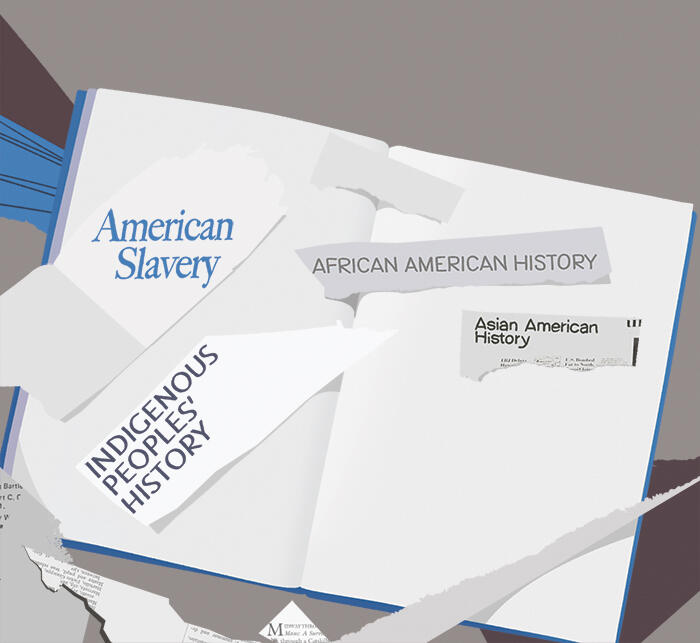

We already know that textbooks and state standards fail to provide comprehensive coverage of American slavery, the modern civil rights movement and other histories involving oppression and resistance. A 2020 CBS News analysis found that seven states don’t explicitly include slavery in their standards. Eight states don’t name the civil rights movement, and 16 identify states’ rights as one cause of the Civil War.

Other histories are also trivialized. According to a 2015 study by Pennsylvania State University researchers, curricula about Indigenous histories tend to be white-centric and cover only pre-1900 events. Only 20 states require learning about the Holocaust, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. And in 2021, Illinois became the first state to require the teaching of Asian American history.

What happens when students can’t contextualize an accurate retelling of history? Historians and educators warn us that history will repeat itself. As with previous eras, we are now witnessing the regression of equitable policies, a rollback of civil rights and backlash against people who protest and demand a better society for all.

We have some dark and ugly moments in our history that we have to reckon with, but discomfort’s OK. Discomfort is where often we find the most growth.

— JAMES WHITFIELD

Truth, Empathy and Making Connections

No matter what is happening around them, though, most students just want to know the truth. They crave it. And in spite of today’s sociopolitical climate, many teachers are still committing to do right by their students.

“What usually happens when students learn something that challenges an existing narrative that they’ve been taught they have questions and they wonder why they didn’t learn that sooner,” says Dallas, Texas, history teacher Jania Hoover, Ed.D. She says parents are piqued, too.

Hoover, a Black woman, has made it her life’s work to help young people connect the past and present. She’s taught U.S. history and a number of other subjects at public schools and now teaches African American and Native American history at a predominately white private school. She’s not afraid to tell the truth about history.

“I became a teacher because I had issues with how Black people were talked about in traditional American history narratives,” Hoover says. “So that’s literally my purpose for becoming a teacher. And of course, you get in a classroom and you learn way more about the whole system. But this manufactured crisis-slash-controversy just makes it even more proof that I’m right. That I’m on the side that’s good.”

In her current job, administrators have pushed back on her approach to teaching history. “I was prepared for this because I was getting challenged and criticized for teaching too much about Black people, too much about slavery,” she recounts.

In Birmingham, Alabama, high school economics teacher Disney Weaver helps his students, most of whom are Black, think critically about how suburban communities developed around them. Beyond race-based economic opportunity, he addresses issues such as gender pay disparity. Weaver, a white man, says these discussions can be uncomfortable for some students—yet still necessary for understanding economic principles.

“I’ve said to my principal and others that each day my objective is to commit treason against white economic opportunity and to expose the way in which white business leaders have not just disenfranchised but have limited the economic opportunity of African American entrepreneurs and neighborhoods,” he says.

He adds, “I room for growth for me to make the connection that I’m not just telling you the hard history to discourage, but it’s to empower my students for a better future.”

Discussions about painful events and uncomfortable truths from diverse perspectives not only prepare students to create a better future; it helps them build empathy, too.

“And if you’re empathizing, then you might advocate for some of these policies that might challenge some of these existing power structures,” Hoover says.

Teaching an honest history also uplifts people’s humanity through stories of resistance, which are often omitted from textbooks or unexplored in curricula. Rejecting a white-centric narrative provides students with a clearer picture of the past. For example, emphasizing Indigenous peoples’ fights to stop colonization and elevating Black people’s organizing power tell a fuller, more human story. Starting with local history is one way to find and discuss humanizing stories.

Uplifting Local History

Teachers can’t teach what they don’t know. That’s why it’s critical they learn the history of their communities.

Teaching eighth-grade world history in Jefferson County, Alabama, Nefertari Yancie, Ph.D., understands the importance of local history. When she taught in Birmingham City Schools, she made sure her students visited local museums and landmarks to help them learn about the civil rights movement.

“If we don’t show them what their history is, who they’ve derived from—and I’m not just talking about Black students, I’m talking about all of them—then they’re not going to realize where they’re going and what they can do in the future,” Yancie says.

In parts of Florida, some teachers are diving into uncomfortable local history, with political support and at other times without it. In 2021, Florida lawmakers banned teaching “critical race theory” but had previously passed a law requiring schools to teach about the Holocaust, the Ocoee Massacre and other historical events.

“The museums have already developed lesson plans and activities to teach the Ocoee Massacre and what caused it and the ramifications of it for local museums in that area,” says Bernadette Kelley-Brown, Ph.D., an associate professor at Florida A&M University who serves on the Florida African American History Task Force. “And they have been supported by the Florida legislature and the governor’s office. So on paper, it says one thing, but in the support of agencies who are responsible, it says that there is another whole conversation.”

Described by historian Paul Ortiz as the “single bloodiest day in modern American political history,” the Ocoee Massacre happened when white mobs killed Black residents and ran others out of town on Election Day 1920. That history is integral to students understanding their community today, as they may wonder why the town was all-white for decades.

Florida lawmakers codified teaching African and African American history into law in 1994, but Kelley-Brown says the state isn’t doing enough to ensure these lessons are integrated into the U.S. history curriculum. Of the state’s 67 school districts, Kelley-Brown says only 10 are faithful in their teaching of African and African American history.

The Florida African American History Task Force is working to help teachers implement lessons about the Ocoee Massacre and other African American histories in K-12 classrooms. Ultimately, Florida educators have the grounding to do this history justice and can start locally.

Teachers Won’t Back Down

For many teachers, political pressure won’t stand in the way of doing what’s right: teaching within the guidelines of states’ standards and leading with historical facts backed by original documents.

“If my job fires me for telling the truth, I don’t need to work there,” Hoover says. “I’m just even more focused on telling an honest history. The kids are seeing and hearing these controversies. … They’re dialed in.”

The National Education Association, American Federation of Teachers and the Chicago Teachers Union are among the educator groups making bold, public statements. They say they won’t be bullied into not teaching the truth about U.S. history. Many educators have signed the Pledge to Teach the Truth, advanced by the Zinn Education Project, to continue teaching critical thinking skills and having necessary conversations.

In a joint statement from the American Association of University Professors, the American Historical Association, the Association of American Colleges & Universities, and PEN America, they reject the restrictions anti-CRT bills are placing on schools and note that a white-washed history won’t change the past or improve the future.

A total of at least 151 organizations have signed onto the statement. It says, in part:

“Knowledge of the past exists to serve the needs of the living. In the current context, this includes an honest reckoning with all aspects of that past. Americans of all ages deserve nothing less than a free and open exchange about history and the forces that shape our world today, an exchange that should take place inside the classroom as well as in the public realm generally.”

Finding Support

Hoover says the first line of defense against today’s dishonest history movement is school administrators.

“What happens in a lot of these cases when parents complain [is the] administration folds,” Hoover says. “They need to trust their educators as professionals, as people that have degrees in teaching. And a lot of people have degrees in the content that they are teaching.”

Teachers committed to this work don’t have to look any further than readily available resources to accurately teach history. It’s as simple as finding online tools, such as Learning for Justice’s Teaching Hard History resources.

“The information is there,” Hoover says. “Teaching Hard History, those key concepts, those videos—they’re short enough you can just play them in your class. … So you don’t have to create these resources; you just have to find and use them.”

Hoover recommends that teachers who feel isolated align themselves with other teachers who are passionate about teaching honest history.

“Especially if you’re in some of these rural communities, it can feel like you’re swimming upstream,” Hoover says, “but there are people who are committed to doing this work.”

Hope for the Future

Former principal James Whitfield recognizes that we’re in the middle of a typical American cycle. As he puts it, the enlightenment of people yields an inevitable backlash because “you’re infringing on somebody’s privilege.”

He hadn’t heard of critical race theory until it was used to push him out of a job. But he wants to learn more and doesn’t see the theory as a bad thing. Neither does Yancie.

“All CRT is saying is that, in America, we have policies that are racist because this country has an issue with race that we have not settled,” Yancie says. “And we have to talk about that. There’s no way around it because our students live that. It’s their reality. If we don’t talk about it or where it came from, then we’re doing them a disservice.”

Whitfield says he’ll continue anti-racism and truth-telling work with educators. He is hopeful.

“We have some dark and ugly moments in our history that we have to reckon with, but discomfort’s OK,” he says. “Discomfort is where often we find the most growth. … I think the large majority of people are going to take this opportunity … and lean into the discomfort that sometimes we have to experience to have progress.”

Coshandra Dillard is a senior writer for Learning for Justice. Before joining LFJ, she was a freelance writer and magazine editor. She also worked as a health journalist for more than eight years. Additionally, Coshandra has experience in the classroom, having served as a substitute teacher for grades K-12. You can follow her on Twitter @CoshandraD_LFJ.

Spread the word