Washington D.C., October 28, 2022 - Sixty years ago today, the most dangerous days of the Cuban Missile Crisis came to an end—and the cover-up of the deal that would end the crisis began. President John F. Kennedy rejected Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev's proposal to formalize a secret missile trade on paper. Kennedy then secretly orchestrated a political attack on U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, who had advised the president to make the missile deal, in a controversial article published by the Saturday Evening Post, according to private letters published for the first time today by the National Security Archive. The correspondence between a co-author of the article, Stewart Alsop, and the magazine’s executive editor, Clay Blair Jr., indicates that President Kennedy himself was the “unadmiring official” quoted in the story as stating, “Adlai wanted a Munich. He wanted to trade U.S. bases for Cuban bases.”

The accusation about Stevenson, which Kennedy’s own White House aides called “false and malicious,” created a political furor in Washington when the article, “In Time of Crisis,” was published in early December 1962. But the article helped Kennedy cover up the fact that he had implemented Stevenson’s private advice during the missile crisis and secretly traded the removal of U.S. missiles in Turkey for the withdrawal of the Soviet missiles in Cuba.

In a letter dated March 10, 1964, Alsop’s editor, Clay Blair Jr., pressed him to write a “tell all” article about Kennedy’s involvement in the attack on Stevenson. “Imagine, if you will, the impact of such a revelation by you just a few weeks before the Democratic convention opens. Startling?” Blair then identified the pivotal piece of evidence—the page of the article manuscript where Kennedy, identified as “an unadmiring official,” penciled in the “Munich” quote. “Do you, by chance, have in your possession an original copy of the manuscript with JFK’s editing marks on it?” Blair asked. “If so, it would certainly lend to the piece’s importance as well as stifle, in advance, the automatic reaction of the doctrinaire liberals who refuse to believe that The Man ever really said that about Adlai.”

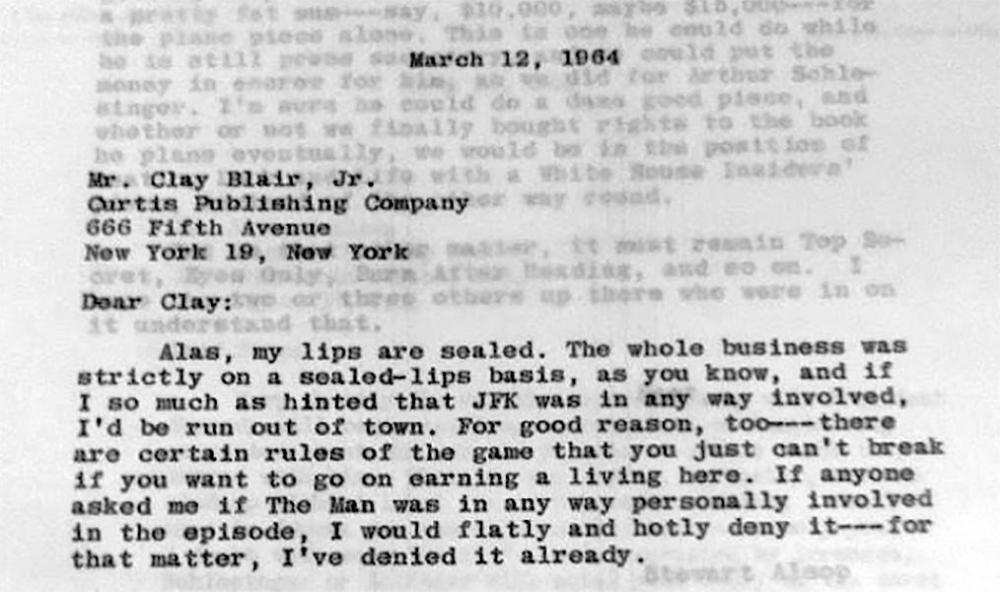

The first paragraph of a private letter from Stewart Alsop to his editor at the Saturday Evening Post, Clay Blair Jr.

In his response, Alsop reminded his editor that the president’s role “must remain Top Secret, Eyes Only, Burn After Reading, and so on.” “The whole business was on a sealed-lip basis, as you know, and if I so much as hinted that JFK was in any way involved, I’d be run out of town,” he advised. The manuscript pages, he said, had been returned to Kennedy and destroyed. “I sent the ms. to Himself as a Christmas present, through Charlie [Bartlett, co-author of “In Time of Crisis”]. It has long since been reduced to ashes,” Alsop wrote. “It would have made an interesting footnote to history, at that.”

The letters were obtained by University of California Emeritus historian Gregg Herken and quoted in his 2014 book, The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington. Herken wrote that “The president had penciled in the ‘Munich’ line when he annotated a typescript of the draft article,” drawing on notes from an interview with Alsop’s son, Joseph Wright Alsop VI, who said his father had told him “that it had actually been JFK who added the phrase ‘Adlai wanted a Munich’ in his own handwriting.”

The widely circulated attack on Stevenson inoculated the White House from speculation that there had been a quid pro quo to end the missile crisis, while elevating President Kennedy’s steely resolve as the key factor that forced Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to “blink” and retreat. Indeed, the Saturday Evening Post article, as missile crisis historian Sheldon Stern observed, “squared perfectly with the emerging administration cover story that the president had rejected a Cuba-Turkey missile trade and had forced the Soviets to back down.”

On the 60th anniversary of the day the missile crisis abated, and the dire threat of nuclear war subsided, the National Security Archive is posting a selection of key U.S. and Soviet documents that record how the White House effort to cover up the real resolution of the crisis evolved. The documents include the translated texts of Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin’s cables to Moscow, reporting on his meetings with Attorney General Robert Kennedy; the private correspondence sent by Khrushchev to the president on October 28, 1962, seeking to affirm in writing the verbal deal that Robert Kennedy had made with Dobrynin to trade the U.S. missiles in Turkey for the Soviet missiles in Cuba; the tape recordings of President Kennedy’s phone conversations with former presidents Dwight Eisenhower, Harry Truman and Herbert Hoover, during which Kennedy denied any quid pro quo deal had been made to end the missile crisis; and the unpublished letters between Stewart Alsop, co-author of the controversial Saturday Evening Post article, “In Time of Crisis,” and his executive editor, Clay Blair Jr., which reveal that the president played a significant role in crafting the article.

“The true story behind the resolution of the missile crisis was for years kept secret in one of the most consequential cover-ups in the history of U.S. foreign policy,” observed Peter Kornbluh, who directs the Archive’s Cuba Documentation Project. “A generation of scholars, analysts, foreign policy makers and even presidents were deprived of a full understanding and appreciation of how the leaders of the superpowers avoided nuclear catastrophe. It is a history the international community needs to know because it remains immediately relevant to the events of today.”

Acknowledgement: The National Security Archive is grateful to George Washington University historian James G. Hershberg and the Cold War International History Project for pioneering work on the issues addressed in this posting.

Spread the word