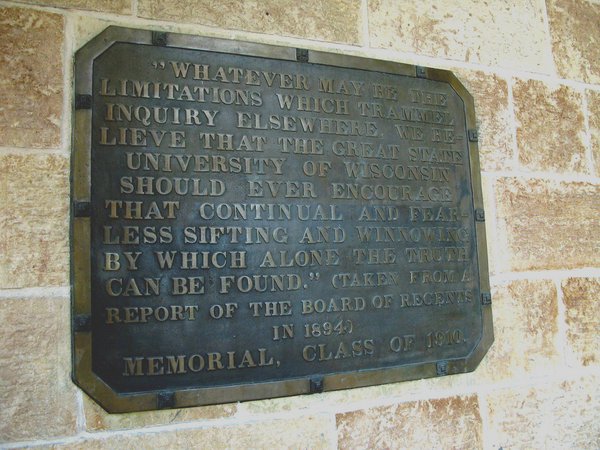

On the wall of Bascom Hall at the University of Wisconsin–Madison hangs a plaque that famously proclaims: “Whatever may be the limitations which trammel inquiry elsewhere, we believe that the great state University of Wisconsin should ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found.”

These words are taken from an 1894 ruling by the UW Board of Regents in defense of a professor named Richard Ely, then-director of the university’s School of Economics, Political Science, and History. But the words did not end up on Bascom Hall, where the university brass is located, at the UW–Madison’s instigation. Rather, this happened due to the efforts of others including Fred MacKenzie, managing editor of La Follette’s Magazine, now The Progressive, acting on a suggestion from the legendary muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens.

MacKenzie passed this suggestion on to the senior class of 1910’s memorial committee, which liked the idea, especially given the Regents’ recent censure of a UW–Madison sociology professor for inviting anarchist Emma Goldman to speak to his students. The committee’s chair inexpertly fastened the letters to a piece of plywood and had the plaque cast, at a cost of $25.

The famed “sifting and winnowing” plaque that hangs on the Bascom Hall exterior at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, where Fredric March’s name has been removed from a performance space he helped to create. (Spencer9/Flickr)

But, according to a 2019 UW–Madison article, “The Regents rejected the plaque, saying the students had been influenced by radicals.” While the plaque “moldered” in the building’s basement, committee members launched a pressure campaign that included placards on Madison streetcars, chiding the Regents’ stance. Others took up the cause.

“What is there in this declaration that can embarrass this university in the light of day?” asked the Wisconsin State Journal in an editorial, “Let the Regents answer.” In 1915, the Regents relented and the plaque was installed, exactly where it hangs today.

The 1894 case involved a complaint lodged against Ely, known for “his progressive views and interest in social reforms and organized labor,” by state schools Superintendent Oliver E. Wells. Wells had alleged, in a letter to The Nation, that Ely encouraged strikes and boycotts and taught students socialism and other “vicious theories.”

In a four-day trial, the Regents heard testimony from prominent academics including Brown University President E. Benjamin Andrews, who said getting rid of Ely “would be a great blow at freedom of university teaching in general and at the development of political economy in particular.” Ely also weighed in: “If I am slaughtered, others in universities will perish, and what will become of free speech, I do not know.”

The Regents cleared Ely unanimously, issuing its eventually famous “sifting and winnowing” statement. The words are often interpreted to mean that a university should let all points of view be heard. But there is another, equally important message: that “the truth can be found” through honest inquiry, and that finding it matters. This is where the University of Wisconsin, hardly alone among institutions, is failing miserably.

Exhibit A: the UW’s disgraceful treatment of Fredric March.

March, a star of stage and screen who died in 1975 at age seventy-seven, was in his day “as central in the old Hollywood firmament as Tom Hanks is today,” according to one writer in The New York Times. He starred in films including Inherit the Wind, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and the original A Star Is Born. He is one of only two actors (along with Helen Hayes) to win two Oscars and two Tonys, including one for his stage portrayal of James Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.

In 1919 and 1920, while he was a senior at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, March was a member of an honors society of students called the Ku Klux Klan.

That, of course, sounds terrible, and has been treated as such. But, as The Hollywood Reporter put it in a recent article, getting to the truth “requires interested parties to dig deeper than a tweet or a blog post.” It calls for some sifting and winnowing.

In October 2017, after the discovery that March and another prominent UW alum for whom facilities in the student union were named belonged to this group, the UW–Madison chancellor at the time, Rebecca Blank, appointed an ad hoc committee to look into the matter. It met several times before issuing a thirty-one-page report in April 2018 which found “no evidence that this group was ever affiliated with the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan” or engaged in violence. Indeed, when an actual campus chapter of the Knights of the KKK launched in 1922, after March had graduated, the group to which he had belonged promptly changed its name to Tumas, whose multiple meanings include, fittingly enough, “truth.”

Citing the university’s stated commitment to “fearless sifting and winnowing,” the committee members, which included several people of color, rejected arguments that anyone who belonged to a group called the Ku Klux Klan should be either banished or absolved. They acknowledged the shock that this name and its history evoked, but said “we resist the impulse to resolve this sense of shock by purging the names from our campus.”

Rather, the committee members advised, “the history the UW needs to confront was not the aberrant work of a few individuals but a pervasive culture of racial and religious bigotry, casual and unexamined in its prevalence, in which exclusion and indignity were routine, sanctioned in the institution’s daily life, and unchallenged by its leaders.” They called on the university to do “a great deal more than unpleasant reminders.” Instead of renaming facilities, they urged “substantial institutional change to address the legacies of this era.”

Slim chance of that.

The release of the ad hoc committee report prompted some UW–Madison students to file a “hate and bias report” with university officials. The university in May 2018 covered up March’s name from a performance space that he had played a role in creating, along with that of the other alum from an art gallery in the same building; both names were later removed. In 2020, UW–Oshkosh officials also purged March’s name from its campus theater.

These decisions have come under deserved criticism, in large part due to the efforts of George Gonis, a UW–Madison alum who thinks it ought to matter that March was actually not a member of a national hate group but rather a lifelong champion of civil rights.

Gonis, a Milwaukee-based journalist and historian, has unearthed records showing that March as a teenager gave an anti-white-supremacy speech; was a primary sponsor of Marian Anderson’s historic 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial (held after she was denied use of a smaller venue due to her race); met with Harry Belafonte and Martin Luther King Jr. and a few dozen others for a strategy session at a New York apartment in 1963; joined James Baldwin, Ossie Davis, Sidney Poitier, and others in sending a telegram criticizing President John F. Kennedy’s failure to protect the rights of the nation’s Black citizens; and delivered the keynote speech at the NAACP’s celebration, in 1964, of the tenth anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

March is, Gonis says, “one of Hollywood’s greatest racial justice activists ever.”

A letter written by Gonis calling on the UW–Madison to reverse its decision was signed by thirty prominent individuals in 2021 and another two dozen in 2022. The signatories include actors Louis Gossett Jr., Mike Farrell, and the late Ed Asner, Langston Hughes’s biographer Arnold Rampersad, and Fighting Bob La Follette biographer Nancy Unger.

“We ask and urge the return—with all possible dispatch—of Fredric March’s name to a place of honor on both the UW–Madison and the UW–Oshkosh campuses,” the letter says, adding that the “creed” of sifting and winnowing “demands both admitting and then correcting mistakes.”

“The name of the campus’s Ku Klux Klan seems to have been an accident,” John McWhorter, a Black opinion writer for The New York Times and Columbia University associate professor, wrote in a column last year. “The students who got March’s name taken off those buildings made a mistake, as did the administrators who seemingly too scared of being called racists to take a deep breath and engage in reason.”

This fall, Turner Classic Movies celebrated March’s 125th birthday by airing several of his films along with a video by TCM host Ben Mankiewicz calling on the UW–Madison to reexamine the allegations that caused “unfair damage to his reputation.”

But the university is unmoved. Completely.

“There are some things in our country’s history that are so toxic that you can never erase the stain, let alone merit a named space in our student union,” Blank wrote in a 2021 letter to The New York Times. “Membership in a group with a name like that of the K.K.K. is one of them.”

John Lucas, a university spokesperson, recently told The Hollywood Reporter, “There are no plans for the institution to revisit the issue.”

There should be. If the sifting and winnowing “by which alone the truth can be found” matters, and it does, then the truth itself must matter, too. Reality is more important than perception, for seekers of the truth. All the folks at the UW–Madison need to do is read the writing on the wall.

Bill Lueders, former editor and now editor-at-large of The Progressive, is a writer in Madison, Wisconsin.

Since 1909, The Progressive has aimed to amplify voices of dissent and those under-represented in the mainstream, with a goal of championing grassroots progressive politics. Our bedrock values are nonviolence and freedom of speech. Based in Madison, Wisconsin, we publish on national politics, culture, and events including U.S. foreign policy; we also focus on issues of particular importance to the heartland. Two flagship projects of The Progressive include Public School Shakedown, which covers efforts to resist the privatization of public education, and The Progressive Media Project, aiming to diversify our nation’s op-ed pages.

You have the power to make a difference at The Progressive by giving us the strength to grow—allowing us to dig deeper, hit harder, and pull back the curtain further to hold accountable those who abuse power! The Progressive, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) and all donations are tax-deductible to the full extent of the law.

Spread the word