It is a truth universally acknowledged that an American in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a mortgage. I don’t know if you should buy a house. Nor am I inclined to give you personal financial advice. But I do think you should be wary of the mythos that accompanies the American institution of homeownership, and of a political environment that touts its advantages while ignoring its many drawbacks.

Renting is for the young or financially irresponsible—or so they say. Homeownership is a guarantee against a lost job, against rising rents, against a medical emergency. It is a promise to your children that you can pay for college or a wedding or that you can help them one day join you in the vaunted halls of the ownership society. In America, homeownership is not just owning a dwelling and the land it resides on; it is a piggy bank, where the bottom 50 percent of the country (by wealth distribution) stores most of its wealth. And it is not a natural market phenomenon. It is propped up by numerous government interventions, including the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. America has put a lot of weight on this one institution’s shoulders. Too much.

The consensus that homeownership is preferable to renting obscures quite a few rotten truths: about when homeownership doesn’t work out, about whom it doesn’t work out for, and that its gains for some are predicated on losses for others. Speaking in averages masks the heterogeneity of the homeownership experience. For many people, homeownership is a largely beneficial enterprise, but for others, particularly young, middle-income and low-income families as well as Black people, it can be risky. This critique isn’t new (not even at this magazine); in fact way back in 1945, the sociologist John Dean summed up many of my concerns in this quote from his book Homeownership: Is It Sound?: “For some families some houses represent wise buys, but a culture and real estate industry that give blanket endorsement to ownership fail to indicate which families and which houses.” This is my central critique: At the margin, pushing more people into homeownership actually undermines our ability to improve housing outcomes for all, and crucially, it doesn’t even consistently deliver on ownership’s core promise of providing financial security.

Luck Isn’t an Investment Strategy

As the economist Joe Cortright explained for the website City Observatory, housing is a good investment “if you buy at the right time, buy in the right place, get a fair deal on financing, and aren’t excessively vulnerable to market swings.” This latter point is particularly important. Although higher-income Americans may be able to weather job losses or other financial emergencies without selling their home, many other people don’t have that option. Wealth building through homeownership requires selling at the right time, and research indicates that longer tenures in a home translate to lower returns. But the right time to sell may not line up with the right time for you to move. “Buying low and selling high” when the asset we are talking about is where you live is pretty absurd advice. People want to live near family, near good schools, near parks, or in neighborhoods with the types of amenities they desire, not trade their location like penny stocks.

A home is bound to a specific geographic location, vulnerable to local economic and environmental shocks that could wipe out the value of the land or the structure itself right when you need it. The economic forces that have juiced demand to live in America’s coastal cities are extremely strong, but one of the pandemic’s enduring legacies may be a large-scale shift of many workers to remote environments, thereby reducing the value of living near the business districts of superstar cities. Making bets on real estate is tricky business. During the 1990s, Cleveland’s house prices outpaced both the national average and San Francisco’s. How confident are you that you can predict the ways in which urban geography will shift over your tenancy?

Timing isn’t the only external factor determining whether homeownership “works” for Americans. Paying off a mortgage is a form of “forced savings,” in which people save by paying for shelter rather than consciously putting money aside. According to a report by an economist at the National Association of Realtors looking at the housing market from 2011 to 2021, however, price appreciation accounts for roughly 86 percent of the wealth associated with owning a home. That means almost all of the gains come not from paying down a mortgage (money that you literally put into the home) but from rising price tags outside of any individual homeowner’s control.

This is a key, uncomfortable point: Home values, which purportedly built the middle class, are predicated not on sweat equity or hard work but on luck. Home values are mostly about the value of land, not the structure itself, and the value of the land is largely driven by labor markets. Is someone who bought a home in San Francisco in 1978 smarter or more hardworking than someone trying to do so 50 years later? More important, is this kind of random luck, which compounds over time, the best way to organize society? The obvious answer to both of these questions is no.

And for people for whom homeownership has paid off the most? Those living in cities or suburbs of thriving labor markets? For them, their home’s value is directly tied to the scarcity of housing for other people. This system by its nature pits incumbents against newcomers.

Housing Policy Is Built on a Contradiction

At the core of American housing policy is a secret hiding in plain sight: Homeownership works for some because it cannot work for all. If we want to make housing affordable for everyone, then it needs to be cheap and widely available. And if we want that housing to act as a wealth-building vehicle, home values have to increase significantly over time. How do we ensure that housing is both appreciating in value for homeowners but cheap enough for all would-be homeowners to buy in? We can’t.

What makes this rather obvious conclusion significant is just how common it is for policy makers to espouse both goals simultaneously. For instance, in a statement last year lamenting how “inflation hurts Americans pocketbooks,” President Joe Biden also noted that “home values are up” as a proof point that the economic recovery was well under way. So rising prices are bad, except when it comes to homes.

Policy makers aren’t unaware of the reality that quickly appreciating home prices come at the cost of housing affordability. In fact, they’ve repeatedly picked a side, despite pretending otherwise. The homeowner’s power in American politics is unmatched. Rich people tend to be homeowners and have an outsize voice in politics because they are more likely to vote, donate, and engage in the political process.

In a 2018 survey of a sample of America’s mayors—in which most registered serious concerns about housing affordability—less than 25 percent of respondents agreed with the statement “It would be better if housing prices in my city declined.” Three years later, after skyrocketing housing prices made a long-simmering housing crisis real for even high-income Americans, still just 40 percent of participating mayors “strongly” or “somewhat” agreed with that statement. The authors note that they found “somewhat higher support for this position among mayors of Western cities and more expensive cities.”

Relying on a Single Asset Isn’t Smart

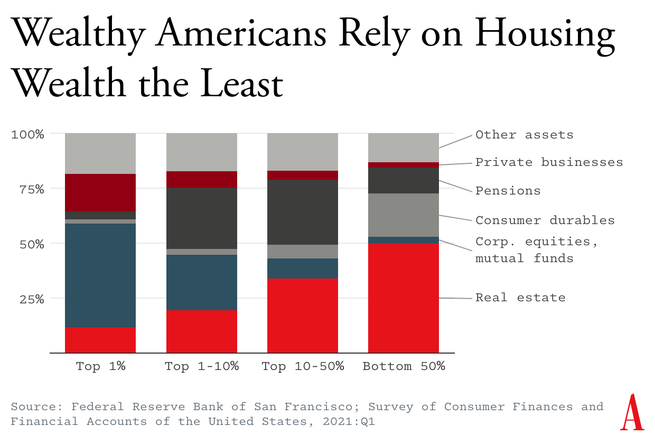

The core benefit that homeownership is meant to offer is financial security. Yet in numerous ways it actually exposes homeowners to more risk. By concentrating wealth in one asset, middle-class homeowners are particularly exposed to regional economic and environmental shocks, like if a large employer decides to relocate or a hurricane devastates downtown. Events outside your control can completely wipe you out. It’s no surprise then that the wealthiest Americans are the least likely to store their wealth in their homes. Certainly, they benefit from owning their homes, but the wealthier the American, the more likely they are to hold their assets in equities and mutual funds. (During the pandemic, this difference made the rich even richer, as the stock market outperformed the housing market.)

Policy makers in favor of pushing more people into homeownership often note that housing wealth is regularly used for socially desirable ends, such as starting a business, retiring, or helping finance higher education. But when I asked Zillow economists how people use their home equity, they painted a different picture. Over the past two years, they found that roughly 22 percent of people tapped into their home equity, and that 70 percent of those people used it for home improvements; 39 percent to pay off debt; 29 percent to pay for a car, a vacation, or another costly item; and just 12 percent for college. None of these decisions are bad, per se, but they don’t jibe with common perceptions of how housing wealth is put to use. (Additionally, remodeling with that wealth instead of, say, making more diversified investments actually increases individuals’ exposure to the risks of homeownership.) LendingTree similarly found that home improvement was the top reason for homeowners applying for home-equity loans or lines of credit.

Granted, the past couple of years may have been an aberration; people went crazy for home remodeling during the pandemic. But even pre-pandemic research cuts against common understandings of how homeowners use their equity. In 2011, then University of Chicago economists Atif Mian and Amir Sufi looked at how homeowners responded to rising home values and discovered that newfound equity wasn’t used for further investment or even to pay down expensive credit-card balances but rather largely for home improvement or other consumption. A now-familiar trend emerged in this research as well: Borrowing against home equity is the domain of homeowners in relatively poor financial positions. They found that almost 40 percent of total defaults from 2006 to 2008 were from 1997 homeowners who borrowed aggressively against the rising value of their houses.

People also tend to underrate the hidden costs of owning a home, including property taxes, utilities, maintenance costs, and upkeep. In an interview with UC Berkeley professor Carolina Reid in 2013, a low-income first-time homebuyer explained:

“The three months after we bought the house, we tripled our credit card debt. We were so focused on affording the house, we didn’t think about the moving costs. And things like buying trash cans for the bathroom or curtains. I think I must have gone to Target every day and walked out with $300 worth of stuff.”

Inequality Is Inevitable

Home values do not increase uniformly, which means the gains to homeowners differ by income, by geography, and by race. From 2010 to 2020, 71 percent of the increase in the value of owner-occupied housing accumulated to high-income homeowners. The geographic distribution of housing values may not be predictable, and is sometimes surprising, but it isn’t necessarily random, either. Riskier areas tend to be more affordable areas because the people who can pay to live elsewhere will do so. That means that the riskiest investments, and thus the worst potential outcomes for homeowners, are concentrated among people with less wealth to begin with. These differences are inevitable; that’s precisely why our political obsession with homeownership as an investment is so misguided.

A single-minded pro-homeownership agenda can lead policy makers to ignore massive potential costs. Last year, for instance, NPR found that the Department of Housing and Urban Development had offloaded foreclosed houses in federally designated flood zones on unsuspecting buyers, many of whom were first-time homeowners. A HUD spokesperson justified the move by explaining that the agency wanted to ensure that “property values” were maintained in these areas, so leaving the homes vacant was therefore unacceptable. More so than selling people a vulnerable asset nearly certain to erode their financial stability?

Racial disparities in housing are well-known but worth stressing. In 2018, the Brookings Institute researchers Andre M. Perry, Jonathan Rothwell, and David Harshbarger compared homes in majority-Black neighborhoods with communities that have very few or no Black residents and found that even when controlling for “similar amenities” (school quality, access to businesses, crime), homes in majority-Black neighborhoods are worth 23 percent less, roughly $48,000 a home on average and $156 billion in cumulative losses.

In his book Know Your Price, Perry explains that majority-Black neighborhoods have higher crime rates, longer commute times, and fewer good public amenities (such as high-scoring schools) and private ones (such as highly rated restaurants). Although these factors, of course, affect price, they explain only about half of the differential between Black and white neighborhoods. The rest, Perry attributes to racism. “Value, by and large, is socially constructed, and much of the way we have created practices to value homes are rooted in racist belief systems,” Perry explained to me.

Better government policy can resolve some racial inequities, but not all. Home value is subjective. Obviously labor-market conditions and public investments play a large role, but so do aesthetics and so do sometimes inarticulable feelings of belonging that cannot be quantified or explained, sometimes even to ourselves. When a prospective buyer walks into a neighborhood and sees several Black neighbors, no amount of government legislation can stop them from consciously or subconsciously lowering their assessment of the neighborhood’s value. These subjective assessments create a Black tax on home-price appreciation: The average 2007 owner who sold in 2018 earned a .9 percent annual return while the average Black seller earned a .4 percent return, according to research by the economist Matthew Kahn.

Even when Black Americans do build wealth through homeownership, downturns in the economy wipe them out. According to the Economic Policy Institute, from 2005 to 2009, a time period covering the foreclosure crisis, Black households saw their median net worth fall by 53 percent, while white households saw just a 17 percent decline. And on the flip side, when the housing market is doing well, Black households tend to benefit less than white ones. The Boston Fed estimated that from January to October 2020, as mortgage rates plummeted, 12 percent of white, 14 percent of Asian, and 9 percent of Hispanic borrowers refinanced their homes—whereas only 6 percent of Black borrowers did, likely because of risk factors such as lower credit scores. The researchers found that the savings from refinancing totaled $5.3 billion in payment reductions a year—of which only 3.7 percent went to Black households.

One final inequality that often flies under the radar is generational inequality. When Americans buy homes under the expectation that values always appreciate, that’s an expectation that someone else will pay that increased price. In 2018, writing for City Observatory, the author and housing expert Daniel Kay Hertz aptly described homeownership as a Ponzi scheme: “It is, in other words, a massive up-front transfer of wealth from younger people to older people, on the implicit promise that when those young people become old, there will be new young people willing to give them even more money. And of course, as prices rise, the only young people able to buy into this ponzi scheme are quite well-to-do themselves.”

undamentally, the U.S. needs to shift away from understanding housing as an investment and toward treating it as consumption. No one expects their TV or their car to be a store of value, let alone to appreciate. Instead, Americans recognize that expensive purchases should reflect their particular desires and that the cost should be worth the use they get out of them.

Just as higher-wealth households spread their assets among various equities and mutual funds, so should the government encourage and aid lower- and middle-income households in doing the same. Not only would this shift in emphasis help American families diversify risk, but it would help them avoid many of the unavoidably unequal features of the housing market. As the economist Nela Richardson told Marketplace: “A stock in Apple is the same for everybody.” It doesn’t know whether you are Black or white, rich or poor, and the fortunes of all investors are tied together if the stock market does poorly, meaning highly engaged shareholders will hold companies accountable for poor returns or bad management decisions—a benefit that accrues to all investors.

I should be explicit here: Policy makers should completely abandon trying to preserve or improve property values and instead make their focus a housing market abundant with cheap and diverse housing types able to satisfy the needs of people at every income level and stage of life. As such, people would move between homes as their circumstances necessitate. Housing would stop being scarce and thus its attractiveness as an investment would diminish greatly, for both homeowners and larger entities. The government should encourage and aid low-wealth households to save through diversified index funds as it eliminates the tax benefits that pull people into homeownership regardless of the consequences.

Right now, homeownership is the default option for most people with savings. That’s true in part because of the perceived benefits that I mentioned above but also because we make renting a nightmare in this country. In order for homeownership to be a meaningful choice, tenancy has to be one too. Part of what people are purchasing when they move from being a tenant to an owner-occupant is freedom from landlords.

If we are interested in helping low- and middle-income people live well, we need to fix renting. Some potential policies include increasing oversight of the rental market, providing tenants with a right to counsel in eviction court to reduce predatory filings, advancing rent-stabilization policies, public investment in rental-housing quality, and, most important, building tons of new housing so that power shifts in the rental market from landlords to tenants. Even if nothing changes and America’s love affair with homeownership continues, tens of millions of people will continue renting for the duration of their lives, and almost everyone will rent for at least part of their life. Financial security, reliable and reasonable housing payments, and freedom from exploitation should not be the domain of homeowners.

Let housing be a home; let it provide shelter, access to good jobs, and safe and healthy communities. Just don’t let it be an investment.

Spread the word