Setting aside for a moment the hype, the glitz, the money, the commercials, the athleticism, the scoreboard, and the beer, chili, and wings—everything that comprises the NFL’s Super Bowl experience this weekend—the cold, sad truth remains that football is taking a horrible toll on some of its players. The extent of that price was made clear Monday in new figures released by the Boston University CTE Center.

According to its latest report, the CTE Center has diagnosed 345 former NFL players with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, out of 376 former players who were studied, a rate of 91.7 percent. Two retired players from the two teams facing off in Super Bowl LVII on Sunday—the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles—were among those diagnosed with CTE in the last year. Those ex-players are one-time Eagles quarterback Rick Arrington, who played for them from 1970 to ’73, and former Chiefs defensive tackle Ed Lothamer, who played for two of their Super Bowl teams.

To put those numbers in perspective, a 2018 BU study of 164 brains of men and women donated to the Framingham Heart Study found that only 1 of 164 (less than 1 percent) showed signs of the progressive degenerative brain disease. And that lone CTE case? A former college football player.

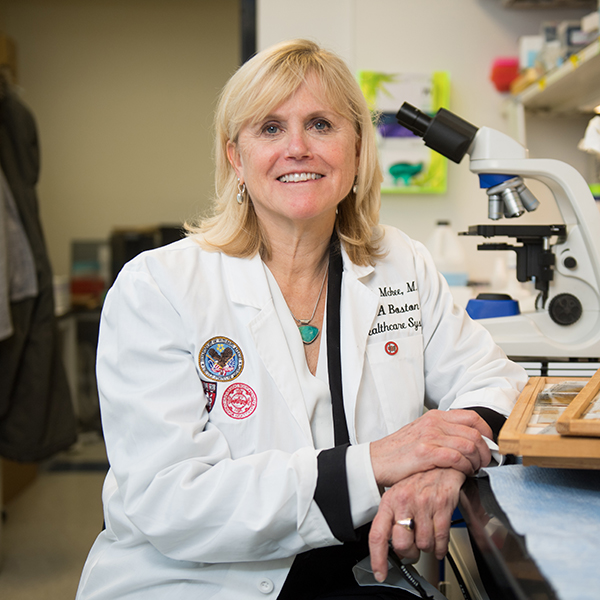

Ann McKee, director of the BU CTE Center. Photo by Cydney Scott

The players “feel invincible, at the top of the game, and I understand that and the power that must hold over them,” says Ann McKee, director of the BU CTE Center and chief of neuropathology at VA Boston Healthcare System. “But they are just unfortunately not living with the real risks of the disease. It makes me sad.”

Amid the frenzy of Super Bowl week, The Brink spoke with McKee about the latest numbers and her hopes for the most-watched and most popular professional sport in America.

McKee, a William Fairfield Warren Distinguished Professor, emphasized that the center’s data does not mean that roughly 92 percent of all former and current NFL players have CTE. She says the prevalence of the brain disease can only be definitively diagnosed after death, which is why the center relies so heavily on brains being donated for study. McKee says the biggest risk factor for CTE is not the violence of one or two isolated head blows, but rather the smaller, repetitive head impacts, like those that football players experience throughout a game or season. Those repeated blows cause a buildup of misfolded tau protein in the brain that is unlike the changes seen from aging, Alzheimer’s disease, or any other brain disease.

CTE research has advanced considerably in the last five years, with McKee’s center set to publish its 182nd study on the disease. “We’d like to thank our 1,330 donor families for teaching us what we now know about CTE, and our team and collaborators around the world working to advance diagnostics and treatments for CTE,” McKee says.

To learn more about the CTE Center, its studies, and its efforts to recruit more participants, scroll to the bottom of the story.

Q&A WITH ANN MCKEE

The Brink: Can you first talk about the timing of this new release, and why you thought it was important to announce these latest numbers this week?

McKee: All eyes are on the Super Bowl. There are real risks to playing football. It’s demonstrable in NFL players. The last time we put this out, in 2017, we had one third of this total number. It’s a reminder of how we’ve become complacent. The NFL hasn’t done anything substantial to prevent CTE or diagnose CTE; the risk is still there. The risk is high. That’s why we released it this week. Also, it’s a message to people who think they might be suffering from CTE, that there is help available. With the Concussion Legacy Foundation, there are resources available directing them to healthcare professionals to assess and diagnose them. And our CTE Center—we do see living people and treat their symptoms. There is a lot of benefit to having a label for your symptoms. Even if the person doesn’t have a cure, just knowing it’s not your fault, but that you have a disease, matters to people.

It seemed like for a little while, there were conversations between you and the NFL. What sort of relationship does the CTE Center have with the NFL today?

No relationship. At one point, in 2010, they gave us money, one million dollars. I have had no contact with the NFL in years.

Does that disappoint you?

It disappoints me only in that I don’t think they are actively pursuing ways to counter this disease. They aren’t working to actively monitor their players, in any substantial way to look at CTE, and lessening the amount of head impacts. They haven’t done anything substantial to reduce repetitive hits.

Are there steps you think could be taken that would make a real difference?

Absolutely. Keeping head contact out of practice. Emphasizing to young players to start playing later. They have endorsed flag football, but they could go further than that. I haven’t seen any attempt to reduce head injuries. They are very involved in concussions. They are not monitoring the amount of head impacts, or intensity of head impacts, they are turning a blind eye to that. There is a lot of, “If I don’t look at it, it’s not there.”

There have been a number of stories over the years about people saying they will no longer watch football. Or that we need to look away. But far and away, it remains the most watched sport in this country.

There is a love for football by the public and individuals that transcends common sense. They are stuck in a denial because the game is so important to them that they refuse to look at the facts.

This season saw a number of incidents in the NFL that raised concern about head injuries, most notably the one with Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovailoa, who seemed to have a seizure on the field following a hit. Did you follow that?

After that with Tua, there were many other incidents. He wasn’t held back after the first hit. He went back and played on Thursday night and had another hit, and it looked like he had a very substantial injury. There was a lot of deep concern for Tua. Then he had a third concussion and did not pass the concussion protocol for weeks and weeks.

I do think the public is becoming wiser to notice these major events. But there is still no embrace of the idea that it’s the little hits, where it looks like nothing happened, that lead the players to deteriorate later.

You have talked before about children playing football. Has your opinion changed?

The longer you can delay playing the better. Physical maturity varies by child. A child needs to be physically well developed. Trained in a way to minimize their risks. And I also encourage young athletes to pursue other sports.

It seems like this is like trying to put toothpaste back in the tube. Football is a multibillion dollar business. It’s ingrained in our culture. Is it going to take the government to get involved to have real change?

It’s foolish for our society to expect that the league that is profiting from this is going to regulate itself. It has to be an outside body. The conflicts are there. It’s so deeply rooted. They will never be able to fully embrace what is happening. Expecting people profiting so clearly from the sport to come up with a solution is not likely.

Are you surprised that more players have not acted with more concern or alarm to your findings over the years?

I actually think I am seeing younger players pay more attention to the potential risk. They are more vocal. More aware of what could happen to them. It takes a long time to change people’s behavior. I am not that surprised. I think it will be slow. But I am encouraged by what happened, even this year. There is a groundswell with the public. As it spreads to all the diverse parts of the US, we will start to see a change.

Will you watch the game Sunday?

I used to love football. I lived it. I just have no interest in it. You can’t do this work for 15 years and have the same attitude about it. Everything looks like a disaster waiting to happen.

Describe your emotions toward football and the NFL? Is it anger? Disappointment? Frustration?

No, not those things. What is the word? [Long pause] Worry and fear. I see that they are celebrities. They feel invincible. At the top of the game. I understand that and the power that must hold over them. But they are unfortunately not living with the real risks of the disease. It makes me sad.

Do you think as the CTE Center’s numbers climb from the hundreds into the thousands, maybe that will make a difference?

I used to think that. I thought 100 would be big. Then 500. I think if we can diagnose it during life that will shock people. People being shocked by it—that will be the change we need.

McKee and her team are inviting former athletes, including women, to participate in research studies designed to learn how to diagnose and treat CTE. The BU CTE Center is collaborating with its education and advocacy partner, the Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF), to recruit former football players and other contact sport athletes to five active clinical studies.

One of the studies, Project S.A.V.E., is recruiting men and women ages 50 or older who played five-plus years of a contact sport, including American football, ice hockey, soccer, lacrosse, boxing, full contact martial arts, rugby, and wrestling.

S.A.V.E. stands for Study of Axonal and Vascular Effects from repetitive head impacts. The major goal is to determine how repeated head impacts from playing contact sports can lead to long-term thinking, memory, and mood problems. The results could highlight strategies to treat and prevent symptoms associated with head impacts from contact sports. Learn more about Project S.A.V.E. and four other studies enrolling participants here. To sign up for future clinical studies, enroll in the CLF research registry.

Spread the word