Bob Cherny, veteran labor historian at San Francisco State, close to his subject, fell seriously ill a decade ago but happily recovered; through the process, this book has been more than twenty years in the making. His subject, notorious for smoking cigarettes madly and through some parts of his life also drinking heavily, had become a legend long before his passing.

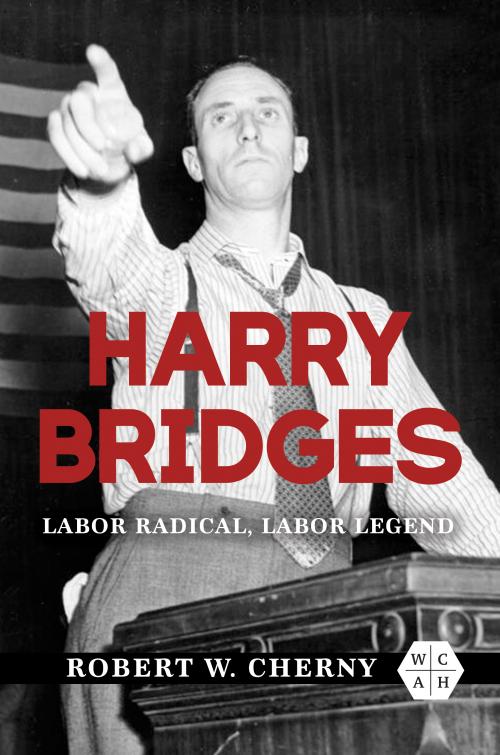

Harry Bridges: Labor Radical, Labor Legend

By Robert W. Cherny

University of Illinois; 478 pages $55.00

Clothbound: $55.00; E-book: $19.95

January 10, 2023

ISBN: 978-0-252-04474-8 and 978-0-252-05379-5

Who else in labor, apart from outright gangsters and the more numerous corrupt bigshots, had successfully evaded prosecution by US administrations and the FBI for generations? Whose faithful dominians could shut down a port in hours? Or propel the Hawaiian labor movement from weakness to strength? The list of plaudits is long, and safe to say, was bitterly resented by AFL chiefs until Harry’s dying days.

It’s a fine saga, never before told fully or with such a sense for the subject. Alfred Renton Bridges, born at the turn of the twentieth century to an upper middle class family in a suburb of Melbourne, had every good reason to take the easy path upward, but the sharp rise of the Australian Labour Party offered the world something new: the world’s first governing social democratic party, urging nationalization of monopolies (also urging racist policies on non-white immigrants). An avid reader seeking adventure, Harry took to the seas. Experiencing the brutality normalized by the sea trade, he joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1921 in New Orleans. Traveling to San Francisco the next year and applying for US citizenship (he lied about his age, providing grounds later on to deport him), he was ready for action.

The degradations of portside workers were notorious, the corruption of craft union officials legendary. Worst of all was the “Blue Book,” San Francisco’s variant of the “American Plan” of the 1920s to break unions or render them toothless. Longshoremen lived in a world of casual and often brutal, dangerous labor, each day uncertain. Like some of the other labor radicals around him, Bridges joined the “red” Marine Workers International Union in 1932 and became one of the editors of the Waterfront Worker, which circulated within the conservative International Longshoremen’s Association. Early on, and definitely influenced by Communist national policies, Bridges and other activists pressed the issue of racial equality, an important step in a marine industry where race lines had been and often continued to be crucial.

The longshore strike that became the San Francisco General Strike of 1934 reset calculations on all sides. Conservative labor leaders, opposing the strike, stood discredited. Communists, well placed, self-sacrificing and effective, emerged triumphant but (unlike European communists) unwilling to make their own influence public. The Roosevelt administration wanted no outright class warfare and the Bay Area’s maritime businessmen’s leadership ultimately agreed to terms. Harry Bridged emerged triumphant.

Bridges’ influence and that of the newly-organized ILWU spread rapidly, and this despite bitter opposition from AFL conservatives, including East Coast longshore officials and the Seamens Union of the Pacific (known best for its occasional militancy and its determined exclusion of non-whites). Bridges rose with the CIO and the CIO in California rose with him.

Cherny, spending months in the Moscow archives, seems to have determined that Bridges used the CP far more effectively than the reverse, in a relationship quietly accepted on all sides (of the Russian-oriented Left). The US Party leadership had no choice, and if other leftwing union leaders became “submarines” by dropping the party membership, Harry wisely had nothing to drop. This became crucial in the first major phase of legal efforts to deport him, from the later 1930s until US entry into War in December, 1941.

Trotskyists most especially would rage at Bridges for enforcing a no-strike pledge during the War, and would have a point (if they needed one) in the ILWU’s seeming indifference to the AFL-led Oakland General Strike in 1945. Bridges shrewdly declined to oppose the Marshall Plan and gave only tepid support to Henry Wallace in the 1948 Progressive Party campaign. He was removed from the Northern California office of the CIO, and of course the ILWU was purged from the CIO a half-decade before the merger of the two federations. Efforts by teamsters and others to raid the ILWU mostly failed, and meanwhile expansion into further fish factories (up the coast from California) and creation of unions in Hawaii, made Bridges almost a Cold War winner.

Aging and stress got to him. He was smoking like a chimney, as they used to say, taking barbiturates to calm his nerves during the 1960s, and after a failed first marriage and amidst a happier second one, had four children to support. Like Bridges himself, his faithful following was aging, and the “B men” working within the ships claimed they faced super-exploitation without ILWU support. Stan Weir, an old friend of the reviewer and an adamant Trotskyist in the lead of the struggle, was in part carrying out an old vendetta. But in truth, Bridges had definitely worked out a relationship with Pacific Maritime Association, foreshadowing the later acceptance of containerization in return for good wages and retirements for those who remained on the job. From 1970 to 1982, he actually served on the San Francisco Port Commission, where many of the crucial business decisions were hammered out.

The Right and the Center made one more big effort to get rid of Harry. The House Committee on UnAmerican Activities hilariously charged that Berkeley’s political cadre, from local anti-racist demonstrations at hotels to the Free Speech Movement, operated as puppets of Bridges. Attorney-General Robert Kennedy attempted to oust Bridges’ leadership by legal maneuvers, and successfully hurt Bridges’ prestige indirectly, thanks to John Kennedy’s support within the Bay Area Black community during the 1960 election and after.

And yet Bridges pressed on and on, helping to rally antiwar activists within the public and the labor movement, while militantly in support of civil rights. By 1970, Bridges had created a modus vivendi with the popular San Francisco mayor, Joseph Alioto. After Bridges retired officially in 1977, members of the ILWU felt more comfortable placing him in the history of the union. He passed in 1990, the flags at City Hall went to half-mast, the LWU shut down the ports for part of a day, and dignitaries by the dozens paid homage to him. The labor movement would not see his like again.

[Paul Buhle is a sometime labor historian who has become a nonfiction, historical comics maven. His latest is a graphic adaptation of W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, drawn by Paul Peart-Smith.]

Spread the word