The Iraq Invasion 20 Years Later: It Was Indeed a Big Lie That Launched the Catastrophic War

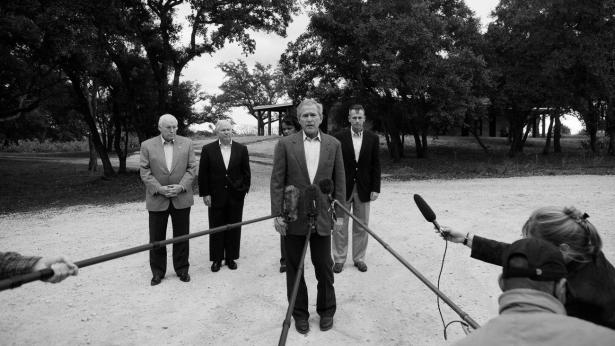

Before there was Donald Trump’s Big Lie, there was George W. Bush’s Big Lie.

Twenty years ago this week, Bush and his sidekick Vice President Dick Cheney launched a war against Iraq. They greased the way to this tragic conflagration with the false claims that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein possessed an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction that directly threatened the United States, and that he was in league with al Qaeda, the perpetrators of the horrific September 11 attack. Their invasion, which led to the deaths of over 4,000 American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians—and the violence and instability in the region that resulted in ISIS—is now widely considered to have been a strategic blunder of immense proportions. Three months before he died in 2018, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz), a leading advocate of the war and the post-invasion troop surge, published his final book, The Restless Wave, which included a self-damning verdict: “The principal reason for invading Iraq, that Saddam had WMD, was wrong. The war, with its cost in lives and treasure and security, can’t be judged as anything other than a mistake, a very serious one, and I have to accept my share of the blame for it.”

Other one-time cheerleaders for the Iraq war have voiced regret and, occasionally, shame. In a 2018 book, Max Boot, an analyst who was once deeply ensconced in the world of neocon foreign policy, wrote, “I can finally acknowledge the obvious: It was all a big mistake. Saddam Hussein was heinous, but Iraq was better off under his tyrannical rule than the chaos that followed. I regret advocating the invasion and feel guilty about all the lives lost.” Three years earlier, New York Times columnist David Brooks, who had been a loud (and naive) beater of the war drums in 2003, opined, “he decision to go to war was a clear misjudgment.” Last week, in the Atlantic, David Frum, the pro-war speechwriter for Bush who coined the “Axis of Evil” phrase that justified targeting Iraq (and North Korea and Iran), noted the decision to invade was “plainly” unwise and that the war was a “misadventure.”

Let’s give one or two hurrahs for those who can declare they got it wrong. Yes, this conclusion is now obvious, given that no significant WMDs were found in Iraq after American bombs and troops were unleashed on the country and that the invasion, contrary to the assurances of the Bush-Cheney administration and its cocksure neoconservative allies, did not trigger a flowering of democracy in the Middle East.

Yet it’s one thing to acknowledge a misstep in policy judgment; it’s quite another to admit to abetting a fraud. Many of the Iraq War regretters insist they pursued the war in good faith predicated on solid assumptions and propelled by genuine concern for US security. What they don’t confess to is being part of an effort to purposefully bamboozle the American public and whip up support for the war with scare-’em tactics and disinformation. Frum, who has become a pal of mine during the Trump era, provides a good example. In his essay, he challenges the Bush-lied-and-people-died view, noting, “I don’t believe any leaders of the time intended to be dishonest. They were shocked and dazed by 9/11. They deluded themselves.”

This self-delusion argument—we believed what we said—is often packaged with the contention that the Bush-Cheney crowd rendered their decisions on the basis of flawed intelligence that stated Iraq had WMDs, and, thus, these leaders did not intentionally misrepresent the threat.

But this is a phony narrative. The intelligence assessments that suggested Iraq possessed significant amounts of WMDs and was close to developing a nuclear weapon—produced under tremendous pressure from the Bush White House—were often disputed by experts within the intelligence community. (And later, but before the invasion, these findings were challenged by UN WMD inspectors who were scrutinizing Iraq.) Yet Bush, Cheney, and their top aides (Donald Rumsfeld, Paul Wolfowitz, Scooter Libby, and others) embraced these problematic evaluations, as well as assorted and unproven (or disproven) reports, in order to justify the case for war and—here’s the key point—oversold these findings to the public. Meanwhile, they issued overwrought statements about the supposed threat from Iraq that either were unsupported by the faulty intelligence or utterly baseless. In short, Bush and Cheney did lie, and those that marched with them toward war were part of a campaign deliberately fueled with falsehoods. (At one point, Bush even discussed with British Prime Minister Tony Blair concocting a phony provocation that could be used to start the war.)

In our 2006 book, Hubris: The Inside Story of Spin, Scandal, and the Selling of the Iraq War, Michael Isikoff and I chronicled numerous instances when Bush and his lieutenants mischaracterized the WMD threat and the purported (but largely nonexistent) tie between Saddam and al Qaeda. Let’s start with Cheney. In August 2002, as the Bush administration kicked off its campaign to win public support for an invasion of Iraq, the vice president, speaking to a convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, declared, “Simply stated, there’s no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction. There is no doubt he is amassing them to use against our friends, against our allies, and against us.” But at that point, there was no confirmed intelligence establishing that Saddam had revived a major WMD operation nor that he intended to strike the United States with such arms.

In fact, the most recent intelligence assessments at the time had concluded Iraq was not the dire danger that Cheney had claimed. The previous year, Secretary of State Colin Powell had testified to Congress that Iraq remained “contained,” that its military was “weak,” and that “the best intelligence estimates suggest that they have not been terribly successful” in developing chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. In late March 2002, Vice Admiral Thomas Wilson, the chief of the Defense Intelligence Agency, in little-noticed testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee, stated that the Iraqi military was “significantly degraded” and that Saddam possessed only “residual” amounts of WMD, not a growing arsenal. He made no reference to a nuclear program or any ties between Saddam and al Qaeda.

While Cheney was building up support for the invasion at this VFW convention, General Anthony Zinni, who had been commander in chief of the US Central Command, was on the stage. He was surprised by Cheney’s stark and harsh remarks about Iraq. Years later, he recounted his reaction in a documentary: “It was a total shock. I couldn’t believe the vice president was saying this, you know? In doing work with the CIA on Iraq WMD, through all the briefings I heard at Langley, I never saw one piece of credible evidence that there was an ongoing program.” Put simply, Cheney was lying.

Of course, there’s more.

Cheney repeatedly cited a report that 9/11 conspirator Mohammed Atta had secretly met in Prague with an Iraqi intelligence officer. This was supposedly evidence of a nefarious plot linking Saddam and al Qaeda. Yet the CIA and the FBI had investigated and found no evidence that such an encounter had occurred. This conclusion was conveyed to Cheney, but he continued to publicly refer to the unconfirmed Prague meeting. Cheney was purposefully disseminating disinformation to bolster the impression that Saddam was in cahoots with the evildoers of 9/11. This is a damning example of Cheney knowingly citing discredited intelligence to score points. The 9/11 Commission later affirmed that the report of a Prague meeting was bunk.

Bush, too, pushed the Saddam-al Qaeda link. In November 2002, he stated that Saddam “is a threat because he’s dealing with al Qaeda.” Weeks earlier, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had asserted he possessed “bullet-proof” evidence that Saddam was connected to Osama bin Laden. In March 2003, Cheney insisted that Saddam had a “long-standing relationship” with al Qaeda. The intelligence did not show any of this; no “bullet-proof” evidence was ever revealed. Bush, Cheney, and Rumsfeld were making it all up. As the 9/11 Commission later noted, there had been no intelligence confirming significant contacts between Iraq and al Qaeda. Here was another instance in which Bush and Cheney were not misled by flawed intelligence; they were promoting false information.

They also deliberately overinflated the most dangerous piece of the supposed threat posed by Saddam: Iraq’s nuclear program. In September 2002, Cheney said there was “very clear evidence” that Saddam was developing nuclear weapons and pointed to Iraq’s acquisition of aluminum tubes that were to be used to enrich uranium for bombs. Condoleeza Rice, Bush’s national security adviser, echoed this claim, stating that these aluminum tubes purchased by Iraq were “only really suited for nuclear weapons programs.” But Cheney and Rice neglected to disclose that there was a heated dispute within the intelligence community about this supposed evidence. The top scientific experts in the US government had concluded these tubes were unsuitable for a nuclear weapons program. Only one CIA analyst—who was not a scientific expert—contended the tubes were smoking-gun proof that Saddam was working to develop nuclear weapons. That was all the Bush-Cheney White House needed. It embraced the weaker case and ignored the more-informed analysis. Cheney and Rice were cherry-picking—choosing bad intelligence over good—and not sharing with the public the better information that undermined their ultimate objective.

That was just one of the falsehoods and exaggerations about WMDs that Bush and his crew deployed to rig the national debate in favor of war. In October 2002, Bush said that Hussein had a “massive stockpile” of biological weapons. But as CIA Director George Tenet noted in early 2004, the CIA had informed policymakers that Iraq may have possessed some lethal biological agents, but the agency had “no specific information on the types or quantities of weapons agent or stockpiles at Baghdad’s disposal.” The “massive stockpile” was a fabrication.

And here’s another whopper: In December 2002, Bush declared, “We do not know whether or not has a nuclear weapon.” That was not what the National Intelligence Estimate produced that fall had stated. As Tenet would later testify, “We said that Saddam did not have a nuclear weapon and probably would have been unable to make one until 2007 to 2009.” Bush made it seem that US intelligence believed it was possible that Saddam already possessed a nuclear weapon when the intelligence was clear that Iraq, whatever nuclear program it might have maintained, had not reached that point.

There are many other instances of Bush, Cheney, and their aides misrepresenting the facts to grease the way to war. (Secretary of State Colin Powell’s presentation to the UN in February 2003 that laid out the Bush administration’s rationale for war was full of false and misleading information. In 2016, he called it a “great intelligence failure.”) Yet Bush defenders and other commentators have insisted there was no deliberate effort to con the public. They point out that Bush and his national security team felt the threat was real and believed that Saddam had stockpiled WMDs and was in league with al Qaeda. On key fronts, they were convinced that they knew better than the available intelligence.

In his new book on the Iraq war, Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq, noted historian Melvyn Leffler dismisses the question of Bush’s pre-war prevarication:

When critics blame Bush personally or his advisers more broadly…they tend to obfuscate the larger dilemmas of statecraft that inhered after 9/11. Bush failed not because he was a weak leader, a naive ideologue, or a lying manipulative politician…Tragedy occurs not because leaders are ill-intentioned, stupid, and corrupt; tragedy occurs when earnest people and responsible officials seek to do the right thing and end up making things much worse.

For Leffler, who based much of his book on interviews with Bush-Cheney officials, the war was a disaster but not a dishonest enterprise. It was a case of earnestness gone awry.

That lets Bush and Cheney off the hook. The war was a catastrophe falsely pitched to the American people. Whether or not their intentions were honorable, Bush, Cheney, Rice, Rumsfeld, and their comrades adopted dishonorable means to gin up popular support for the invasion of Iraq. Two decades later, it remains much easier for many to acknowledge the war was a miscalculation than a lie. Yet it was both. It was promoted by Bush and his minions with a reckless disregard for the truth and with hype that was fueled by falsehoods and designed to generate fear instead of serious and reasoned public discussion. Bush and Cheney sold it wrong and they got it wrong. Without all the misrepresentations, unfounded assertions, and exaggerations would this calamitous war have occurred? Perhaps. We will never know. But it should not be forgotten that this debacle of death and destruction was not only a profound error of policymaking; it was the result of a carefully executed crusade of disinformation and lies.

===

Spread the word