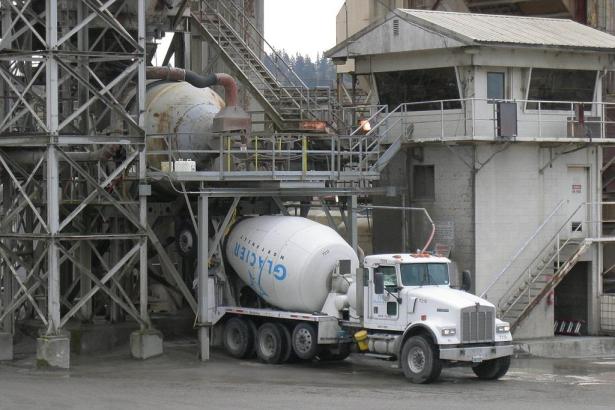

On the face of it, last Thursday’s Supreme Court ruling returning a lawsuit to a state court looks bad for unions. Eight of the Court’s nine justices ruled in Glacier Northwest v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Local Union 174 that the union of the cement-mixer drivers based in Tukwila, Washington, could be sued by their employer for damages inflicted on the employer’s property; in this case, concrete that had dried and hardened before it could be poured. The Washington State Supreme Court had tossed the employer’s suit, saying that state laws in such matters were preempted by the National Labor Relations Act, and that jurisdiction belonged to the NLRB. Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s opinion said that that court had erred, and the lawsuit could continue.

Many in the labor movement had feared that the Court’s ruling in this case would significantly impinge on unions’ right to strike. It didn’t quite work out that way, as it focused so narrowly, and unusually, on the particulars of the case (and may well have gotten those particulars wrong) rather than any underlying laws.

Barrett’s opinion doesn’t dispute that strikes generally inflict economic damage on employers—at least, a loss of revenue. That’s entirely permitted by the NLRA, Barrett noted. The ruling also cited the Court’s 1959 decision in San Diego Building Trades Council v. Garmon, which stated that when the activity in question “is arguably subject” to the NLRA, “the States as well as the federal courts must defer to the exclusive competence of the National Labor Relations Board.” Indeed, Garmon was the basis of the Washington court’s refusal to try the case.

Nevertheless, Barrett ruled that the union’s conduct was so deliberately destructive of property that it wasn’t even “arguably subject” to the NLRB’s jurisdiction.

And yet, consider the following sentence about the Teamsters, which begins her statement of the “facts” in the case:

“Their labor union allegedly designed the strike with the intent to sabotage Glacier’s property.”

Allegedly?

On the 2017 day that cement-mixer drivers for the Glacier Northwest company went on strike, the drivers struck while a number of them were already on their routes, which Barrett also acknowledges is NLRA-protected conduct. (Indeed, strikes generally begin when workers are at work; you can’t walk off the job when you and your fellow workers are at home asleep at 2 a.m.) The workers drove their mixers back to the company’s yard and kept the mixers turning, which keeps the concrete from hardening.

However, Barrett notes, “the Union did not take the simple step of alerting Glacier that these trucks had been returned.”

This somehow presumes that company managers wouldn’t have noticed that a number of trucks had suddenly reappeared in the yards, hours before they were scheduled to. That aside, in its suit, Glacier Northwest alleged that hardening concrete risked damaging the trucks themselves, though it also admitted that no trucks had in fact been damaged. It continued that its supervisors had to pour out the concrete in a safe location, though some of it, once poured, then hardened and ceased to be usable.

The Court doesn’t usually deliver rulings that assess the factual details of a case, confining itself almost always to the issues of constitutional law.

For its part, the Teamsters argued that it told drivers to return the trucks to the yard and to keep their mixers turning, thereby not intentionally damaging Glacier Northwest’s property, which is conduct the NLRA expressly forbids. Union lawyers further argued that previous Court rulings had made clear that the spoiling of perishable goods could not be the subject of lawsuits, and that jurisdiction in such cases belonged to the NLRB. (They cited one decision about strikers who handled raw poultry, another about striking milk truck drivers, and a third about striking cheese processors.)

Let’s stop for a moment and consider where the Court is headed on this. As a guide, here’s an assessment from Catherine Fisk, the Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong Professor of Law at UC Berkeley, and one of the nation’s leading labor law scholars, who wondered aloud to the Prospect, “Is this a special rule for cement trucks? Distinguishing between poultry, milk, and cheese spoilage on one side and cement on the other?”

Barrett asserted in the ruling that “by reporting for duty and pretending as if they would deliver the concrete, the drivers prompted the creation of the perishable product.” But how is that different from the milk truck drivers of yore striking while en route, or the poultry workers separating the legs from the thighs and only then walking off the job, leaving the wings still affixed to the breasts? To be sure, concrete weighs more than chickens and cheese, but if that’s the basis of a Supreme Court ruling, the Court could at least do us the courtesy of stipulating the exact poundage at which the NLRB’s Garmon jurisdiction grinds to a halt.

As Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson noted in her dissent, the Court doesn’t usually deliver rulings that assess the factual details of a case, confining itself almost always to the issues of constitutional law. And yet, Barrett’s opinion reads almost entirely like that of a county court trial judge, weighing management’s claims against the workers’. And even then, it begins with the word “allegedly”—accepting, as it does, the company’s statement of the facts, hedged only by that adverb. One lawyer to whom I spoke said that in asking the Court to dismiss this case outright, the union’s lawyers inadvertently enabled the Court to accept as fact the submission from the company. In light of the extensive documentation those lawyers have also produced of the union instructing its drivers to return the trucks and keep them mixing, however, several other attorneys have told me that the original trial court could well reject the company’s claims, as could the NLRB, which has yet to rule on the case.

All that said, why on earth did Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor join with the Court’s six conservatives in signing on to Barrett’s opinion? Kagan and Sotomayor, after all, have a long history of supporting workers’ collective and individual rights, and are, if anything, staunch guardians of the rights enshrined in the NLRA.

For that, we need to consult the concurring opinion from Clarence Thomas, which Neil Gorsuch signed onto as well. In it, Thomas suggested that the Court should go much further than it did in this case and get into the more fundamental question of whether the NLRA’s right to preempt state courts as laid down in Garmon shouldn’t be subject to the Court’s revision or revocation. “We should carefully reexamine whether the law supports Garmon’s unusual pre-emption regime,” Thomas wrote, while noting that Barrett’s governing opinion didn’t even touch upon that larger topic.

In light of the Thomas-Gorsuch opinion, there’s been considerable speculation that Kagan and Sotomayor went along with Barrett in a de facto deal to fend off the possibility of a ruling that did indeed strike down Garmon and thereby give (largely right-wing) judges in (largely right-wing) states the go-ahead to start issuing rulings that fined unions for the financial damages that employers incurred in the course of a strike. And even if that opinion didn’t go that far, it could have done more overtly, with support of all six conservative justices, what Thomas and Gorsuch came close to doing in their concurrence: inviting the enemies of unions to file a case that directly challenged Garmon.

That was precisely the decision that unions had feared might come out of the Glacier Northwest v. Teamsters case, which explains the relief with which many unions greeted last Thursday’s ruling. “It’s not good,” AFL-CIO Senior Counsel Craig Becker told the Prospect, “but it’s not that bad compared to what it could have been.”

Coincidentally, these were almost the exact words spoken by Democratic members of the House and Senate about the debt ceiling deal they sent to the president, also on Thursday.

Thus ended the “not that bad compared to what it could have been” week in the nation’s capital.

Spread the word