Most people in the United States have a stove in their kitchen. But how did this “must-have” come to be?

In a time before central heating and electricity, stoves were big business. But their legacy wasn’t just food and warmth: historian Howell J. Harris writes that the stove industry of yore pioneered the phenomenon of modern marketing. Harris tracks the history of stovemaking in the nineteenth century as businesses turned from small to mass manufacturing.

“Stovemakers developed methods of product differentiation, began to establish valuable brand identities, reached out to their consumers, and built their own direct-sales networks, at a time when few other manufacturers, particularly in the metalworking trades, saw any necessity to do likewise,” notes Harris.

At the time, hardware manufacturers didn’t market their own goods. Instead, wholesalers took on the responsibility for them. Stoves were manufactured at furnace foundries and sold at local warehouses. But with the dawn of the stove-specific foundry and a dramatic improvement in transportation beginning in the 1830s, manufacturers took responsibility for their products.

No longer able to rely on local markets alone, these stove innovators attempted to distinguish individual brands. They patented new features and created model names—lots of them. Harris notes that a staggering four-fifths of all design patents in the 1840s, and two-thirds of those issued in the 1850s, had to do with stoves and their features.

The mass production of stoves made for more similarity across markets, though Harris points out that put extra pressure on smaller features like handy design innovations and add-ons intended to make stoves stand out. Stoves weren’t just stoves any more: they were Jewett Stoves, St. Lous Air-Tights, Franklin Saddlebags.

These metal behemoths made their way to major cities by rail and ship, then to “stove districts” and stores. In non-urban areas, retailers purchased merchandise from cities and managed the shipping process. Many of these retailers were tinware peddlers turned tinware store owners with vast distribution networks and sales territories. They cleaned up travel-worn stoves, installed, and even repaired them while overseeing complex credit and barter systems.

Traveling salesmen dubbed “stove drummers” crisscrossed the nation, selling stoves and collecting on debts. “They traveled light, carrying trade gossip, catalogs, and not much else, visiting retailers in their own premises,” Harris writes. These salespeople also provided customer service and rudimentary market intelligence, reporting back to headquarters on how consumers like the stoves and what the competitors were selling.

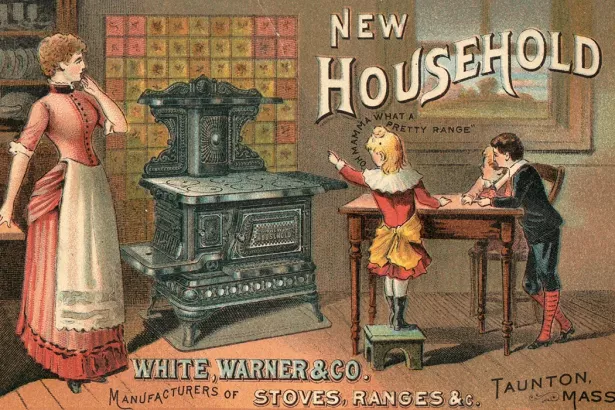

The stove boom ended in the late nineteenth century, but by then the die had been cast. Even as stove prices fell, Harris writes, stovemakers achieved “universal market penetration…transforming stoves into objects bought as consumption items, on grounds of their style, and even beauty, as well as their functional utility.”

The strategies stove salespeople cooked up are still used today, even if the products themselves have changed.

Resources

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Spread the word