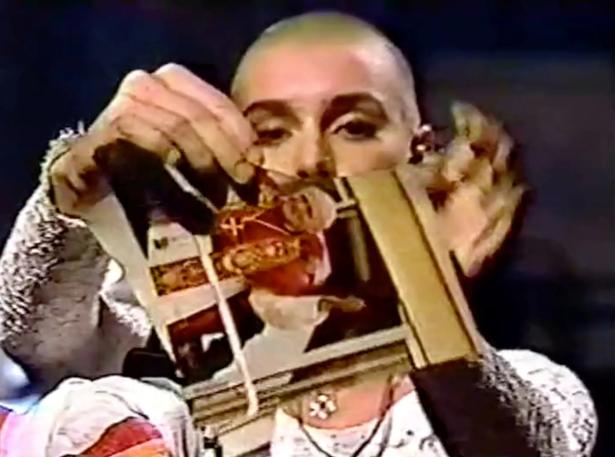

Thirty years ago this week, Sinéad O’Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live,” effectively destroying her mainstream career with a single act of protest against the Catholic Church.

Then 25, the Grammy-winning Irish singer was an unlikely pop star. Known for the raw, emotive power of her voice and her equally fierce resistance to industry pressure — most famously, by shaving her head — O’Connor had risen to international fame with her transcendent cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” and her vulnerable, tear-streaked performance in its accompanying video.

A sharp critic of racism and misogyny in the music business who refused to play the national anthem before her concerts, O’Connor was already a controversial figure. But the “SNL” incident — in which O’Connor sang Bob Marley’s “War” before tearing up the photo to protest, she later said, the Catholic Church’s enablement of child abuse — turned her into a full-blown pariah. Two weeks later, O’Connor was booed off the stage at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden and fled, crying, into the arms of Kris Kristofferson.

She has been in pop culture purgatory ever since, continuing to write and perform music for three decades but never coming close to the levels of acclaim or visibility she achieved in the early ’90s.

The ugly incident at the Dylan concert opens “Nothing Compares,” a new documentary that offers a sympathetic reappraisal of O’Connor as an iconoclastic artist whose provocations were decades ahead of their time.

“It made this huge mark on me as a young Irish woman to witness this hero of mine being treated the way she was,” said Kathryn Ferguson, director of “Nothing Compares,” which premiered this week on Showtime. “The seeds for this film were really planted at that moment. It was a story that stuck with me throughout my adult life. I couldn’t understand why there hadn’t been a cinematic feature made about her.”

Ferguson, who grew up in Belfast, recalls her father playing “The Lion and the Cobra,” O’Connor’s debut album, on repeat in the car “as we drove around really gray, Troubles-ridden Northern Ireland in the late ’80s,” she said during a recent Zoom conversation from London. “It became the soundtrack to my childhood.”

When Ferguson was a young teenager, she and her friends discovered O’Connor on their own terms and swiftly fell in love: “We just felt like we needed her.”

As a graduate student many years later, Ferguson contacted O’Connor’s management team about using some of her music in her thesis film, a connection that eventually led to Ferguson directing the video for O’Connor’s song “Fourth and Vine” in 2013.

“I remembered all of this passion I’d had as a young teenager,” Ferguson said, “and I just really wanted to try and work out how to make this film.”

She spent much of the next five years “talking incessantly” about the project before it finally started to come together in early 2018. The timing was right: The #MeToo movement was surging in the U.S. and elsewhere. In Ireland, same-sex marriage had recently become legal and abortion was about to follow. “The world was on fire with women speaking out,” Ferguson said. “It felt a wee bit mad that this incredible figure wasn’t being mentioned in any of this — someone who has inspired so many of the young activists that were directly changing the country.”

Using extensive archival video — including footage from a wedding at which a teenage O’Connor sang “Evergreen” — brief, stylized re-creations and interviews with O’Connor’s friends, collaborators and contemporaries, “Nothing Compares” traces O’Connor’s meteoric rise from troubled teenager to Rolling Stone cover girl, and her even more precipitous fall from grace. A theme throughout the film is the lingering effect of her traumatic childhood: O’Connor endured physical and emotional abuse at the hands of her mother and was sent to live in a church-run Magdalene home as a teenager.

Most important, “Nothing Compares” features an extensive interview with O’Connor. Her now-gravelly voice can be heard throughout the film, reflecting on aspects of her life and work, but her face appears only in archival video — a conscious filmmaking choice, Ferguson explained:

“Our observation was just how amazingly well the media has done in reducing her voice by mocking and ridiculing her. The key takeaway I wanted was that you heard her voice and it wouldn’t be interrupted. Having her narrate her story on her own terms was of utmost importance.” (The other interviews are also voiceover only.)

O’Connor shares insights into some of her most notable songs and their connection to traumatic chapters in her life — particularly her painful relationship with her mother, who died in a car crash in 1985, a few years before O’Connor burst onto the music scene. She was thinking of her mother while she made the beautifully spare video for “Nothing Compares 2 U,” which primarily consisted of a close-up on O’Connor’s tear-streaked face against a black background.

“Every time I sing the song I think of my mother. I never stopped crying for my mother,” O’Connor says in the film. “I think it’s funny the world fell in love with me because of crying and a tear.”

Notably, the film doesn’t include the song, which was written by Prince. A postscript explains that the musician’s estate denied use of her recording in the documentary.

Ferguson said she was unsure of the exact reason for the refusal: “At the end of the day, it’s their prerogative. We just had to accept that that was the situation and do our best to creatively overcome it.” (A representative for the estate did not respond to a request for comment.)

She was, however, able to secure outtakes from the video, which, along with commentary from director John Maybury and others involved in the production, helps flesh out this vital chapter in O’Connor’s biography.

The documentary intentionally focuses on a brief but formative era in O’Connor’s life. Although it briefly considers the legacy she’s had on other female artists and activists, it does not explore her turbulent journey since 1992, which has included several marriages, a bitter custody battle, mental health struggles and, in January, the death by suicide of her teenage son.

“What went on in this era has had horrific reverberations throughout the rest of her life,” Ferguson said. “But as she says in the film, the positive thing is the commercial career that was annihilated after her actions in 1992 wasn’t the career that she was seeking.”

It’s impossible to know how a Sinéad O’Connor might be received today, given the way the culture wars of the ’90s have metastasized and taken over contemporary political discourse in the United States. But it’s clear that O’Connor was radically ahead of her time in many ways, from her refusal to conform to prescribed gender roles to her songs about police violence against Black people.

Most obviously, the church she criticized for perpetuating child abuse and the exploitation of women has now apologized for wrongdoing in Ireland and around the world. Back in 1992, many people claimed they didn’t understand O’Connor’s message, but as Ferguson noted, O’Connor spoke about her experiences with abuse in many interviews before “SNL” (including one with The Times.) “People just chose not to listen,” she said.

Like many other women who were shunned in the ’90s and dismissed as “crazy,” O’Connor is receiving an overdue cultural reconsideration — one she spearheaded by writing a memoir, “Rememberings,” published to acclaim last year. Her music is finding new fans: “Drink Before the War” was recently included in an episode of “Euphoria.” And “Nothing Compares,” which debuted at Sundance, is bringing O’Connor’s story to a generation of viewers who weren’t yet alive when she immolated her career at 30 Rock.

Ferguson said that many of the screenings get rowdy and emotional. Young people come up to her “with their eyes flashing, just incensed and inspired” by O’Connor’s ordeal. “There’s audible gasps when you get to that backlash moment, because it’s still very shocking to see that this young singer from Dublin is causing this much noise. [Her detractors] obviously saw her as a threat — somebody that had to be silenced.”

Ferguson doesn’t know if O’Connor herself has seen the film, but, she said, “I really hope she feels proud.”

Meredith Blake is an entertainment reporter for the Los Angeles Times based out of New York City, where she primarily covers television. A native of Bethlehem, Pa., she graduated from Georgetown University and holds a master’s degree from New York University.

Spread the word