May 1, 1946 was an unparalleled May Day for the Left in America. Recently discharged veterans joined with teachers, writers, artists, lawyers, and other workers to march triumphantly through Manhattan. “The number of paraders, as we counted them, was over 150,000, and when they packed Union Square, cheering left-wing and Communist leaders and speakers,” the Communist writer Howard Fast wrote in his memoir, Being Red, “one would have said that the future of the left in America was extremely bright and of course they would have been wrong.”

By May Day of 1948, the same Communists who were celebrated only two years earlier became the targets of violent reactionary crowds chanting “Kill a commie for Christ!” Fast was leading the Communist Party’s “culture block” made up of thousands of academics, artists, and writers who quickly found themselves in a street fight with anti-communist students from a nearby parochial school.

The second parade was a bad omen. With the advent of the Second Red Scare and Cold War, Communists soon became the national enemy, seen not as freedom-fighting progressives, as they had been by many on the broad left, but instead as anti-American authoritarians and dangerous subversives. Fast himself was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and was imprisoned when he refused to name names.

Fast was blacklisted from the publishing industry. He was only one of a generation of artists who were purged from America’s mainstream, the blacklist ruining their careers, consigning them to obscurity and often poverty. Many books from that time still remain unpublished and screenplays unmade; cultural figures, once famous, have been largely erased from America’s history.

But within the unwavering terror of the McCarthyist period are stories of resistance. Fast’s experience in prison, for example, led him to write the novel Spartacus, which was later adapted into a screenplay by the Communist writer Dalton Trumbo. When the movie was screened in 1960, after a decade of remaining underground, two Communists’ names illuminated the beginning of the film, a giant middle finger to the reactionaries of the era. This is the story of Spartacus, or how Communists first broke through the blacklists.

“Today’s Prisons Will Be Tomorrow’s Victory”

Howard Fast is one of those forgotten figures in the spotty memory of America’s literary canon. He published his first novel at age eighteen, and spent several decades building his career in publishing, emerging as a popular novelist. He was also an active member of the Communist Party. Before being blacklisted, he was passionately involved with supporting Spanish Republican fighters; in 1945 he joined the executive board of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee. The group was hardly subversive, bringing in donations from the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt and Edith Lehman, the wife of New York governor Herbert Lehman. But political currents shifted, and in 1946 Fast was issued a subpoena to appear before HUAC to give over the donor list.

Fast refused to name names, assured by lawyers that contempt of Congress wouldn’t result in any jail time. But later that same year he was subpoenaed again, this time for a book he’d written on the Yugoslav revolutionary, The Incredible Tito, and his future became uncertain. In 1947, he and ten others from the Refugee Committee were sentenced to prison.

Fast and his comrades had faith in their appeal, but there was little to be done for his reputation and career. “My new book, The American” — a portrait of John Atgeld, the progressive governor of Illinois — “was being trashed mercilessly,” Fast recalled. He was also now under constant surveillance. “My telephone was tapped. Featherbrained FBI agents were slipping into my apartment [during fundraisers] . . . and other agents were following me through the streets,” he remembered.

In 1949, New York schools were instructed to remove any copies of his historical-fiction book, Citizen Tom Paine, from their shelves. J. Edgar Hoover sent agents ordering New York Public Library librarians to destroy Fast’s books. The FBI blocked publishers from printing new works of Fast’s, even some he had written under the supposed anonymity of a pen name.

By 1950, anti-communism had spread, and Fast’s hopes for a reversal of his prison sentence were lost. Fast was booked in a district prison, an experience he recalled as distinctly dehumanizing:

There on long benches sat about a hundred men, black men and white men, all of them naked. They sat despondently, hunched over, heads bent, evoking pictures of the extermination camps of World War Two. . . . The dignity we had clung to so desperately was now taken from us.

He was put in a five-by-seven foot cell with a frightened eighteen year old who’d been in and out of prison since he was twelve and, according to Fast, had been raped by other prisoners over a hundred times. Fortunately for Fast, he was transferred to Mill Point, a minimum security prison in West Virginia.

To those outside the United States, Fast and his imprisoned comrades were martyrs. Rallies and fundraisers were held in support of the imprisoned as international solidarity poured in. The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote the poem “To Howard Fast,” praising Fast’s writing about “black heroes, of captains and highways, of the poor and of the cities,” and lamenting the tyranny of the Second Red Scare, what Neruda called the “gestapo reborn.”

Fast’s imprisonment was a calamity for free speech, but there were also silver linings. He spent much of the end of his term with the Communist novelist Albert Maltz and found solace in his daily work building structures for the prison — his masterpiece was a functioning replica of the famous Manneken Pis statue. The warden of the prison was oddly kind, offering up a typewriter for Fast to write after his daily prison duties.

Fast, himself hoping to use the time to write, was unable to bring himself to commit any words to paper. Instead, he took to researching. He was particularly interested in a 1914 German movement founded by Clara Zetkin, Karl Liebknecht, and Rosa Luxemburg that later merged with the Communist Party of Germany. The name of the group was the Spartacus Group. It was his experience in Mill Point, with all the anxieties and fears that being in prison often invokes, that inspired him to write his novel, Spartacus.

“I never regret the past,” he wrote, “and if my ordeal helped to write Spartacus, I think it was well worth it.” It was in prison, after all, where he “began more deeply than ever to comprehend the full agony and hopelessness of the underclass.” As Neruda wrote in his poem dedicated to Fast, “Today’s prisons will be tomorrow’s victory.”

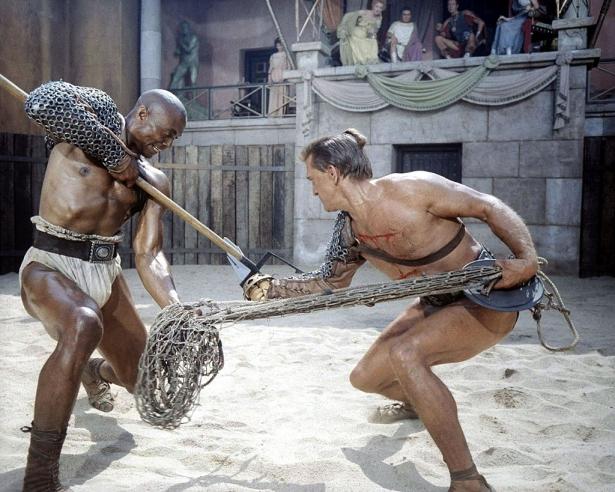

After his months in prison, he was released into a world where the Second Red Scare was in full swing. “The country was as close to a police state as it had ever been,” he wrote in his 1996 introduction to Spartacus. “J. Edgar Hoover, the chief of the FBI, took on the role of a petty dictator. The fear of Hoover and his file on thousands of liberals permeated the country.” In this environment, Fast began the journey of writing a manuscript chronicling Spartacus, the slave who was trained as a gladiator and led a fictionalized slave revolt in ancient Rome.

But with the writing of a book also comes the finding of a publisher. And publishers, in the case of blacklisted writers, were as accessible to them as yachts are to the poor — which is to say, not at all. Fast’s longtime publisher, Angus Cameron at Little, Brown and Company, loved Spartacus and agreed to publish it swiftly and with pride. But then Hoover sent a federal agent to Boston, where he met with the president of the publishing house and delivered direct instructions from Hoover to not publish another book by Fast. The publishing company abandoned the book, causing Cameron to resign in protest.

After several failed attempts at securing other mainstream publishers, Fast resorted to self-publishing. His name and notoriety were enough to spark interest even without a publisher. The book sold well enough. His family shipped forty thousand hardcover copies of the book out of their home.

It would be years before the book would be picked up by mainstream publishers. Eventually it would sell millions of copies and go through over a hundred editions in over fifty-six languages. It would also be turned into a famous film of the same name. But first, Fast and his collaborators would need to break the grip of anti-communism on Hollywood.

Time of the Toad

By 1947, Hollywood was increasingly divided into two polarizing factions: Communist Party members and their sympathizers, and anti-communists who were devoted to rooting them out of the industry. It was the reactionary Motion Picture Alliance that pushed the industry into these opposing camps, with scarcely any room remaining for neutrality.

Hollywood Communists were open in their opposition to antisemitism, fascism, racism, and labor exploitation, contributing under their real names to “dangerous” publications like People’s World, New Masses, and the Daily Worker. “They saw the danger — real danger — to the people in the industry posed by the labor practices of the period,” the liberal California lawyer Carey McWilliams, later editor at the Nation, said in an interview with Trumbo biographer Bruce Cook. “And they knew the Nazis were not playing make-believe.”

After HUAC subpoenaed Hollywood’s “unfriendly nineteen,” more than seven thousand people gathered for a rally at Los Angeles’s Shrine Auditorium before the group’s departure to the capital. They made the most of their trip to Washington, holding rallies in Chicago and New York before arriving at the hearings. Of the original nineteen, the eleven individuals who refused to cooperate with the committee came to be known as the Hollywood Ten. (The eleventh was German Communist playwright Bertolt Brecht, who was living in the United States after fleeing Nazi Germany and then, after his hearing, fled the United States for East Germany.)

Among them was the group’s highest-paid screenwriter and also the committee’s most unfriendly witness: Dalton Trumbo. “our job,” Trumbo told chief investigator Robert E. Stripling after he instructed Trumbo to answer “Yes” or “No,” “is to ask questions and mine is to answer them. . . . I shall answer in my own words. Very many questions can be answered ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ only by a moron or a slave.” On his way out, he yelled, “This is the beginning of an American concentration camp!” That late October of 1947, the Hollywood Ten were cited for contempt of Congress. All were sentenced to prison, Trumbo to a year.

HUAC and the 1947 Waldorf Agreement, the studio-executive pact that enforced the blacklists, devastated many in the entertainment industry. “People would be stunned at the suicides from the period, and incredible things that happened then,” McWilliams recalled. “The use of freedom,” Trumbo wrote in The Time of the Toad (1949), “the actual invocation of the Bill of Rights, is an exceedingly dangerous procedure.” Trumbo directed his moral outrage at not only the conservatives, but also the liberal collaborators with the anti-communist witch hunt, and those who sat by passively.

But far from completely purging the industry of Communists, the blacklists forced them into the shadows. The blacklists created a new market in Hollywood: the black market. Screenplays by blacklistees were sold under false names or under the names of other writers. While waiting for his appeal to go through, Trumbo made a modest living writing pulpy screenplays for the King brothers, a B-movie production house. Between the hearing in 1947 and his entrance into America’s penal system in 1950, Trumbo, under fake names, pumped out eighteen screenplays. “None,” he insisted, “was very good.”

Exhausted from the constant rallies and screenplays, Trumbo almost welcomed certain aspects of prison life. In prison he met moonshiners, bootleggers, and counterfeiters, many of whom were illiterate. He read and wrote letters for one moonshiner named Cecil, whose wife was caring for five sick children on her own, struggling to keep them warm and fed. Those eleven months in Ashland changed Trumbo in many ways. Once a night writer, he now only wrote in the day. Once unaffected by the sound of a whistle, he now stopped instantly to fall in line. But he never abandoned his principles.

After serving their time, John Wexley, Albert Maltz, Ring Lardner, Ian Hunter, Dalton Trumbo, and many other blacklistees lived in exile in Mexico City, seeking work and refuge from the persistent harassment of the FBI. One day, the Canadian-born blacklisted screenwriter Hugo Butler dragged Dalton and Cleo Trumbo out to watch some bullfighting. One bullfight ended in an indulto, or pardoning of the bull, which is given after the crowd waves handkerchiefs in support of a bull’s showcase of bravery. The event inspired Trumbo’s film, The Brave One (1956), a drama following a boy and his bull. The film went on to win an Oscar under Trumbo’s pseudonym, Robert Rich. It was the first fracture in the wall that was the blacklists.

Press caught onto rumors that Trumbo was Robert Rich. Instead of confirming them, he exposed how extensive Hollywood’s black market was by pointing the press to other blacklisted writers who might have written it. By 1956, Trumbo was back in Hollywood and had mastered the art of the black market. He had numerous pseudonyms and writers volunteering their names to help them get into the industry. John Abbott, Sam Jackson, C. F. Demaine, and Peter Finch were just some of his alter egos. What he proved in his strategic elusiveness was that any screenplay could be written by a Communist using a fake name or a front writer. The blacklist was only as effective as the employers willing to enforce it — and the tide was turning.

“I’m Spartacus”

The first draft of the screenplay for Spartacus was written by Fast, but he wasn’t quick enough to finish the job in time. Arthur Koestler’s The Gladiators, a movie with a similar theme, was on the way to production, and Kirk Douglas’s production company, Bryna Productions, which was producing Spartacus, needed to beat it to the screen. So Douglas turned to the fastest pen in the West, Dalton Trumbo — signed under the pseudonym Sam Jackson.

They quickly began filming, but the original director, Anthony Mann, butted heads with Douglas. Apparently forgetting that Douglas was not only the star of the film but also the boss, Mann got himself fired. Douglas replaced him with Stanley Kubrick, whom he referred to as a “cocky kid from the Bronx.” Many problems ensued throughout the filming of the movie. From the censors limiting any vaguely sexual or homosexual content to the bribing of Spain’s Franco government to use soldiers in a scene, the movie was a vast and complex undertaking.

It wasn’t clear at the time of filming whether Trumbo and Fast could be credited on screen. The 1950s were coming to an end, and it was unclear how effective the blacklists were at this point. The debate heated up when Mann spread the news that it was Trumbo, not Sam Jackson, who wrote the movie. Gossip columns picked up the news, and for the first time in a decade Trumbo’s cover was blown.

And then the January 19, 1960, edition off the New York Times was published, proclaiming on the cover that Trumbo would be credited as the screenwriter of Otto Preminger’s upcoming production Exodus. Hollywood was dipping its toes in the tides of the blacklists. Would there be a crackdown in response? If not, would that mean McCarthyism was over? Would audiences boycott the film, or celebrate it? Upon Spartacus’s release, theaters across the country displayed a giant middle finger to the anti-communist repression of the era. Audiences flocked to see a movie whose title screen displayed the names of two convicted Communist subversives, Howard Fast and Dalton Trumbo.

Pickets ensued, but they were relatively reserved. A group called the Catholic War Veterans were the most vocal. (They had been, however, in full support of the English film that came out earlier that year called Conspiracy of Hearts, about Catholic nuns protecting Jewish children from Nazis. The screenplay was credited to Robert Presnell Jr, but was actually written by Dalton Trumbo.)

The blacklists were, for all intents and purposes, broken. In 1960, Kennedy was elected president, and shortly thereafter, he made a trip to a movie theater with his brother. With a number of films they could’ve seen, the Catholic brothers chose no other than Spartacus, crossing the Catholic War Veterans picket to deal a final death blow to the blacklists. When Kennedy exited the theater and was asked what he thought of the film, he responded simply: it was a good film.

“The terrible penalty of crucifixion has been set aside on the single condition that you identify the body or the living person of the slave called Spartacus,” a Roman soldier yells out in a famous concluding scene of Spartacus. Kirk Douglas rises, but is followed in unison with his two neighbors who yell “I’m Spartacus,” as a thousand other slaves rise behind them. Spartacus became a pseudonym for resistance, for liberty.

The story of Spartacus is also the story of the story of Spartacus. Howard Fast and Dalton Trumbo were two of the thousands of Communists in the United States who struggled to survive through the Red Scare. It was a time when, as Trumbo put it, “devils persuad us that freedom is best defended by surrendering it altogether.”

Taylor Dorrell is a writer and photographer based in Columbus, Ohio. He’s a contributing writer at the Cleveland Review of Books, a reporter for the Columbus Free Press, and a freelance photographer.

Subscribe to Jacobin today, get four beautiful editions a year, and help us build a real, socialist alternative to billionaire media.

Spread the word