There are two popular images of Bela Lugosi. Of the two, to put it bluntly, one is incomplete. The other is flat out wrong. The first is to picture him as synonymous with Dracula. While Lugosi did portray the Count in the first sound film adaptation of the story (Max Schreck’s Orlock from Nosferatu is the first silent version, although it was not acknowledged as an adaptation at the time due to Dracula author Bram Stoker’s litigious widow), he only reprised the role once more on film, in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. This image may have been reinforced, however, by his appearances in the non-Dracula vampire films Mark of the Vampire and Return of the Vampire.

The other image comes from Tim Burton’s heavily fictionalized biopic Ed Wood, where Lugosi is played by Martin Landau. While Lugosi’s final work was in Wood’s notorious schlock films, that fact is one of the few things the film gets correct. Landau’s Lugosi is profane, sleeps in a coffin, and hates fellow actor Boris Karloff. None of this is true. Lugosi never swore, slept in a bed, and while he resented Karloff’s success (which he viewed as having been at his own expense) he didn’t hate the man. Even the dogs in the film are inaccurate. Lugosi owned wolfhounds, not the small dogs depicted on screen.

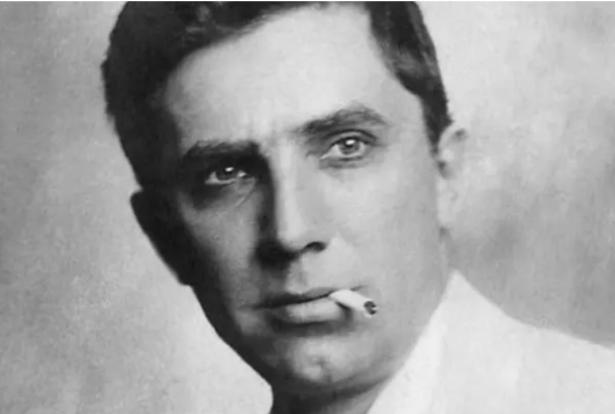

The real Bela Lugosi was born Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó in the Kingdom of Hungary on October 20, 1882. He would take the stage name “Lugosi” in honor of his birthplace, Lugos, which is now known as Lugoj. He had already been a stage actor when he volunteered in the Hungarian army during World War I. Lugosi experienced the horror of being buried alive under his comrade’s corpses during one battle. He also served as a military executioner, describing his experience as a hangman as leaving him “thrilled” but “guilty.” Lugosi was discharged from the Hungarian Army in 1916 due to “mental collapse,” unsurprising when we consider the brutality of the war and his experiences.

After the war, Lugosi became an activist in the Hungarian actor’s union. He was a staunch supporter of the 1919 Hungarian Revolution and the short lived Hungarian Soviet Republic. When Miklós Horthy, a future ally of Nazi Germany, assumed power, Lugosi had to flee for his life. He ended up in New York where he acted in Hungarian plays before being cast in the English language play the Red Poppy. In 1927, he was cast in the role that made him famous: Count Dracula.

One of Lugosi’s earliest supporters was the Communist press. The Daily Worker advertised the play Dracula in its October 1, 1927 issue. The February 2, 1928 Daily Worker praised his “impressive performance” as Count Dracula. The New York edition of the paper advertised the play regularly in its Amusements section, hailing it as “Better than the Bat [a mystery play later adapted for film].” The bourgeois papers could be much less supportive. From the New York Post: “Mr. Lugosi performs Dracula with funereal decorations suggesting … an operatically inclined but cheerless mortician.” The New York Herald-Tribune was of a similar bent reporting that “the torments of the first American performance might have been more alarming had the demon been illustrated less stiffly. … It was a rigid hobgoblin presented by Mr. Lugosi, resembling a wax man in a shop window more than a suave ogre bent on nocturnal mischief-making.”1 It makes one wonder if the Communist Party press ran favorable notices for the star as a way to support him due to him being a socialist political refugee. Lugosi’s charismatic stage performance and his persistent lobbying of Universal Studios, got him the role in the film version.

After his star-making film role in Dracula, Lugosi became a founding member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), who are on strike as of this writing. Another founding member was Frankenstein star, and frequent Lugosi costar, Boris Karloff. Lugosi additionally served on the advisory board of SAG from 1934-1936. The two actors worked to sign up the casts of their films, such as the Bride of Frankenstein, the Raven, and the Invisible Ray. Their efforts paid off when SAG signed its first contract with the Hollywood studios in 1937. Lugosi’s solidarity extended beyond his fellow actors. In 1945 he signed a petition protesting the deportation proceedings against longshore union leader Harry Bridges.2 At this time, Lugosi expressed a more moderate politics from his previous revolutionary socialism. He said he was an “extremely liberal Democrat” and “an avowed Roosevelt disciple.”3 During World War II, Bela Lugosi headed the Hungarian American Council for Democracy. On August 28, 1944 he gave the keynote speech at a 2,000 strong rally in Los Angeles calling on President Roosevelt to loosen immigration restrictions and allow in 2,000 Hungarian refugees. Unfortunately, Roosevelt showed his usual timidity on refugee matters and only allowed in 1,000. To further aid the war effort, Lugosi (ironically given his roles as blood suckers), donated blood to the Red Cross to publicize blood donations.

Lugosi’s political activities caught the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI and the Central Intelligence Agency both opened files on the actor. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) appointed a “Dracula council” to keep tabs on the star. INS even looked into deporting him, despite the fact that he had held American citizenship since 1931. Lugosi probably did himself no favors in the eyes of Red hunters when he contributed a favorable piece to the Communist-affiliated New Masses on the Soviet Union. His work on the Hungarian American Council for Democracy was cited positively in a 1944 issue of that same publication. The Council was later listed as a “subversive” group by the United States Attorney General, along with the Communist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World, and the Socialist Workers Party.

Lugosi was not the only horror star to be targeted by the red-hunters for political activism. Peter Lorre, star of M, and Vincent Price, who had appeared in the Invisible Man Returns, received scrutiny for participating in the anti-HUAC radio broadcast “Hollywood Strikes Back.”4 The two spoke out alongside Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, and other stars. Lorre was also investigated due to his continuing friendship with Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht. Price was unable to find work for a year due to his outspokenness and under pressure from the FBI, had to sign a secret oath that he was not a communist.

One wonders if Lugosi’s late era career woes could be explained by the Red Scare and the Hollywood Blacklist. While his name never appeared on any “official” Blacklist, it’s entirely possible that his career suffered all the same. It’s also possible that Lugosi’s career difficulties were unrelated to the Blacklist, but more due to his age and problems with drugs and alcohol as well as moviegoers changing taste. We’ll probably never know for certain. Lugosi did worry about HUAC’s effect on his reputation. In 1951 he wrote a letter to HUAC’s chair Congressman

John S. Wood. That Wood, an ex-Klansman who allegedly participated in the lynching of Leo Frank became the arbiter of “Un-American Activities,” is surely a testament to capitalist democracy. The actor proclaimed “Communist totalitarianism has always been abhorrent to me. I have never knowingly or willfully given it aid or comfort in any way.” He further declaimed against his involvement in the Hungarian American Council for Democracy, claiming that he was unaware that it was a “Communist front.”5 These denials, whether genuine or not, did not revitalize his career and the actor spent the rest of the 50s in Mystery Science Theater quality productions like Bride of the Monster and Glen or Glenda.

Some of Lugosi’s films contain political and social themes of interest to those who consider themselves on the Left. 1932’s White Zombie, in which he played voodoo master Murder Legendre dramatizes the exploitation of Black Hatians. Legendre uses his zombie slaves to work his sugar mill and increase his wealth. He offers zombie laborers to a plantation owner saying “They are not worried about long hours.” When one of the zombies falls into the mill and is crushed, work continues as normal. Nothing must stop the quest for profits. This is all the more outstanding given that forced labor had been reintroduced to Haiti during the then-ongoing U.S. military occupation. One critic said that the film “provides an important example of the disguised and suppressed radical critique the horror genre can often manifest.”

Another 1932 horror film, Island of the Lost Souls (an adaptation of the Island of Doctor Moreau), contains similar anti-colonial themes. Lugosi has the small, but memorable role of the Sayer of the Law, the mouthpiece of Dr. Moreau’s laws for the Beast Men. At the climax of the film, the Beast Men attack Moreau, after the Doctor has ordered one of them to commit murder. The purpose of the oppressor’s laws are not, in this case, to create a just society, but to ensure control over the masses and he is free to break them when convenient. Moreau defends himself with a whip, the tool of the slaver. This climax was so shocking that the film was banned in many countries. Tellingly, in Australia it was prevented from being shown to Aboriginal audiences, lest they get any ideas of how to deal with their colonial overlords.

1934’s the Black Cat was a highpoint in Lugosi’s filmography. The film was the first to team him with Boris Karloff and both actors give their all. The plot follows Werdegast (Lugosi) and Poelzig (Karloff), both of whom fought on the Russian front during World War I. However, Poelzig betrayed Werdegast and the other soldiers to the enemy and left them for dead. Werdegast gives a powerful monologue saying “Did we not both die here in Marmorus fifteen years ago? Are we any the less victims of the war than those whose bodies were torn asunder? Are we not both the living dead?” According to Paul Buhle, “[Director Edgar G.] Ulmer himself described the film as allegory. He had seen the face of the war’s horror and rendered it in narrative, symbolic form around the twin commanders driven to lunacy by the consequences of their own deeds.”6

Even poverty row Lugosi vehicles are of some interest. His Dr. Carruthers, in the cheaply made the Devil Bat, is seeking revenge on the businessmen who he feels have exploited him to enrich themselves. Lugosi certainly drew on his experiences of having been exploited by Hollywood studios in the role. For Dracula he was paid only $3,500. For White Zombie the pitiable $800. For Son of Frankenstein, arguably his best role, $4,000.7 While Lugosi was not the driving force behind any of his films, it’d be interesting to know what he thought of the ideology of the films he made, particularly Ninotchka, a satire of the USSR in which he played an antagonistic commissar. The New Masses unsurprisingly grouped the film with Comrade X and Chetniks as “putrefying red herrings.”

Anti-fascists, leftists, socialists, radicals, and revolutionaries looking for a horror film to watch this October ought to seek out one of Bela Lugosi’s classics. Please though, try to broaden your horizons beyond Dracula. If you do, you won’t regret it.

More articles by Hank Kennedy.

Cosmonaut is a Marxist magazine for revolutionary strategy, historical analyses and modern critiques. We aim to be a platform of debate and polemic in order to contribute to the formulation of a Marxism for the 21st century. Make socialism scientific again!

Like this article? Take a second to support Cosmonaut on Patreon! At Cosmonaut Magazine we strive to create a culture of open debate and discussion. Please write to us at CosmonautMagazine@gmail.com if you have any criticism or commentary you would like to have published in our letters section.

- David J. Skal The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror (New York: Faber and Faber, 1993) 91.

- Gary Don Rhodes Lugosi: HIs Life in Films, on Stage, and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers (Jefferson: McFarland and Company, 2006) 63.

- Arthur Lenning The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003) 337.

- Paul Buhle & David Wagner Radical America: The Untold Story Behind America’s Favorite Movies (New York: New Press, 2002) 437.

- Rhodes 298.

- Buhle & Wagner 120.

- Lenning 492.

Spread the word