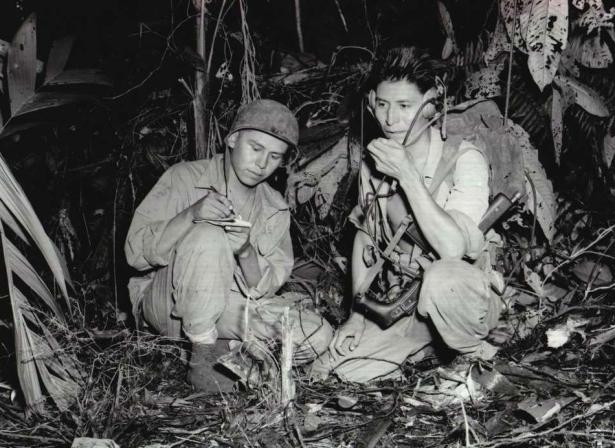

Can’t Understand a Word

FIVE YEARS AGO, on May 28, 2019, Levi Oakes, the last of the Mohawk code talkers, died on the Akwesasne Mohawk Reservation in Quebec. He was 94.

Code talkers were soldiers who served in both the U.S. and the Canadian Army during World War II, Code-talking was a method of using a little-known language to make radio transmissions that are almost impossible to decode because they are spoken in a language that has very few speakers. Hundreds of Native Americans who were fluent in their traditional languages were recruited by both the U.S. and thd Canadian military during World War 2. The link here leads to a 14-minute film about a Cree (not Mohawk) code talker who served in the Canadian army. It’s informative and well done, even if it isn’t about Levi Oakes. Hear the Untold Story of a Canadian Code Talker from World War II | Short Film Showcase

Go Directly to Jail and Stay There

60 YEARS AGO on May 29, 1964, police in Canton, Mississippi, arrested 52 participants in a Freedom Summer demonstration on charges of parading-without-a-permit while demanding the right to become registered voters. All those arrested were kept in a dangerously overcrowded jail for four days because the police would not allow any of them to speak with a lawyer and arrange to get bailed out before June 1. Such police tactics were standard police operating procedure during Mississippi Freedom Summer. https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/oh_freedom/

Deadly Force on Film

87 YEARS AGO, on May 30, 1937, Chicago police opened fire on a group of unarmed striking steelworkers, forcing them to retreat across an open field while the police continued to shoot at them. Ten strikers were killed and more than ninety wounded. Seven of those who died had been shot in the back. The vicious police action was recorded by a newsreel camera crew, but Paramount News kept the footage under wraps for more than a month because, according to the New York Times, "Paramount . . . felt that the showing of the pictures might have resulted in considerable ill-feeling if they had been released immediately." Even when the film was released, it was banned in Chicago. For many more details of how Paramount helped the police get away with murder, click here https://portside.org/2023-05-07/buried-footage-helped-chicago-police-ge…

Just Following Orders

245 YEARS AGO, on May 31, 1779, before the United States had celebrated its third birthday, its infant government established a precedent that has haunted it ever since. George Washington, who was the revolutionary army’s commander-in-chief, regarded many groups of Native Americans to be as big a danger to the success of the revolution as the British Redcoats. As a result, Washington embraced the policy of what he called “the total destruction and devastation” of the Native Americans who controlled most of the land in what is now western New York State.

On this day, Washington prepared written orders to one of his generals, John Sullivan. Washington ordered Sullivan to lead a force of four thousand men against the “Six Nations of Indians,” who were also known as the Haudenosaunee (or Iroquois), and who were the sole inhabitants of almost all the land in western New York State. Washington instructed Sullivan “to lay waste all [the Haudenosaunee] settlements . . . in the most effectual manner, that the country not be merely overrun, but destroyed . . . the total ruinment ot their settlements . . . “ Washington’s orders included almost nothing about military tactics because the Haudenosaunee lacked anything like an army. They were almost all agriculturalists who were considered to be dangerous because they sided with the British. Sullivan was instructed to “capture . . . as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible” and to “ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.”

To carry out Washington’s orders, Sullivan led what is still remembered as the “Sullivan Expedition.” He and his men burned more than 40 unfortified Haudenosaunee settlements, along with their cornfields and orchards of fruit trees. Sullivan and his men encountered almost no resistance nor did they take prisoners, because the Haudenosaunee, who had no means to stop the invasion, fled north and west on horseback and on foot faster than the Sullivan’s slow-moving army could travel.

After 15 weeks of unrelenting scorched-earth destruction, Sullivan led his men south to Pennsylvania, leaving countless acres uninhabited and largely uninhabitable. What had once been Haudenosaunee territory was turned into a no-man’s land that presented a major obstacle to the possibility of the British army attacking Pennsylvania and southeastern New York from their strongholds in Canada. At the time, neither “ethnic cleansing” nor “genocide” were in anyone’s vocabulary, but the policies they represented were well understood.

The Sullivan Expedition, which made it easy for white farmers to settle the fertile area when the war ended, was still well-remembered on its 150th anniversary in 1929. During that summer the State of New York held a month-long commemoration throughout the region. As part of the celebration, the state put up 35 granite monoliths, one in each of the places where Sullivan and his men had destroyed a Haudenosaunee settlement. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sullivan_Expedition

A New Broom for Civil Rights

115 YEARS AGO, on June 1, 1909, the National Negro Conference at the Henry Street Settlement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side wrapped up. During the 2-day conference, some 300 participants heard two dozen presentations delivered by a who’s who of civil rights activists, social reformers, clergy and academics, including presentations by sociologist W.E.B. DuBois on the “Evolution of the Race Problem,” by journalist and civil rights activist Oswald Garrison Villard on “The Need of Organization,” by journalist Ida Wells-Barnett on “Lynching, Our National Crime,” and by civil rights activist Rev. John Milton Waldron on “The Problem’s Solution.”

The presentations made clear that the civil, legal and political status of African-Americans in the U.S. was deplorable and quickly getting worse. Despite the 15th Amendment’s guarantee that African-American men would have the right to vote, during the quarter-century before the meeting took place every state that had joined the Confederacy during the Civil War had made it impossible for Blacks to exercise that right.

During the same period white mobs had staged at least six massive attacks on Black communities in Mississippi, North Carolina, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana and Illinois, killing Black citizens at will and forcing hundreds to flee for their lives, never to return. And the incidence of such violence was growing; three of the six attacks had taken place since 1906. Violence on a smaller scale was routine, and also growing. African-Americans were being forced by white mobs to “run out of town, their lives endangered, their families abused, their property destroyed, merely because they happened to be considered too prosperous, too well-to-do, to suit their neighbors of another race,” according to one of the presentations.

The conference participants agreed to establish the first national organization devoted to protecting the rights of Black citizens – the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/national-association…

Too Young to Work? Think Again.

100 YEARS AGO, on June 2, 1924, the proposed Child Labor Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would give Congress authority to regulate "labor of persons under eighteen years of age," which had passed both houses of Congress by large majorities, was submitted to the states for ratification. Today, a century later, it remains a proposal and not the law of the land because the required three-quarters of the states have not ratified it. With the regulation of child labor still under the control of the individual states, and with the support of the Cato Institute, the Foundation for Economic Education, Commonwealth Foundation and the Foundation for Government Accountability, during the last four years state legislatures in at least 28 states have taken up proposals to make it easier to employ children for profit. Such laws have passed in 12 states. https://stateinnovation.org/childlabor#

149 Joyful Seconds

70 YEARS AGO, on June 2, 1954, Leroy Anderson’s joyous Bugler’s Holiday was first recorded for Decca. If you need a quick pick-me-up, you can listen to it here: 1954 HITS ARCHIVE: Bugler’s Holiday - Leroy Anderson (original version)

Wasn’t That a Time?

75 YEARS AGO, on June 3, 1949, Pete Seeger and Lee Hays gave the premiere performance of their composition, The Hammer Song (better known as If I Had a Hammer), in Manhattan at a fundraising dinner for the Smith Act defendants, 11 leaders of the Communist Party USA who had been indicted (and were later convicted and jailed) for violating the federal law that made it a crime to be a member of an organization advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government. Click here to listen to a performance by The Weavers: Seeger, Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman. The Hammer Song - The Weavers - (Lyrics)

Spread the word