On Tuesday, the AFL-CIO hosted its second annual “State of the Unions” Labor Day event. According to Liz Shuler, President of the AFL-CIO, unions are “on the rise,” “battle-tested,” and “building organizing capacity” like never before. Maybe, but what do the data really tell us about the health and vibrancy of organized labor in 2024 and its nascent efforts to reverse forty years of decline? Let’s look at four key metrics: organizing new workers, collective bargaining and strikes, union finances, and labor democracy and governance.

1. “We’re organizing like never before!”

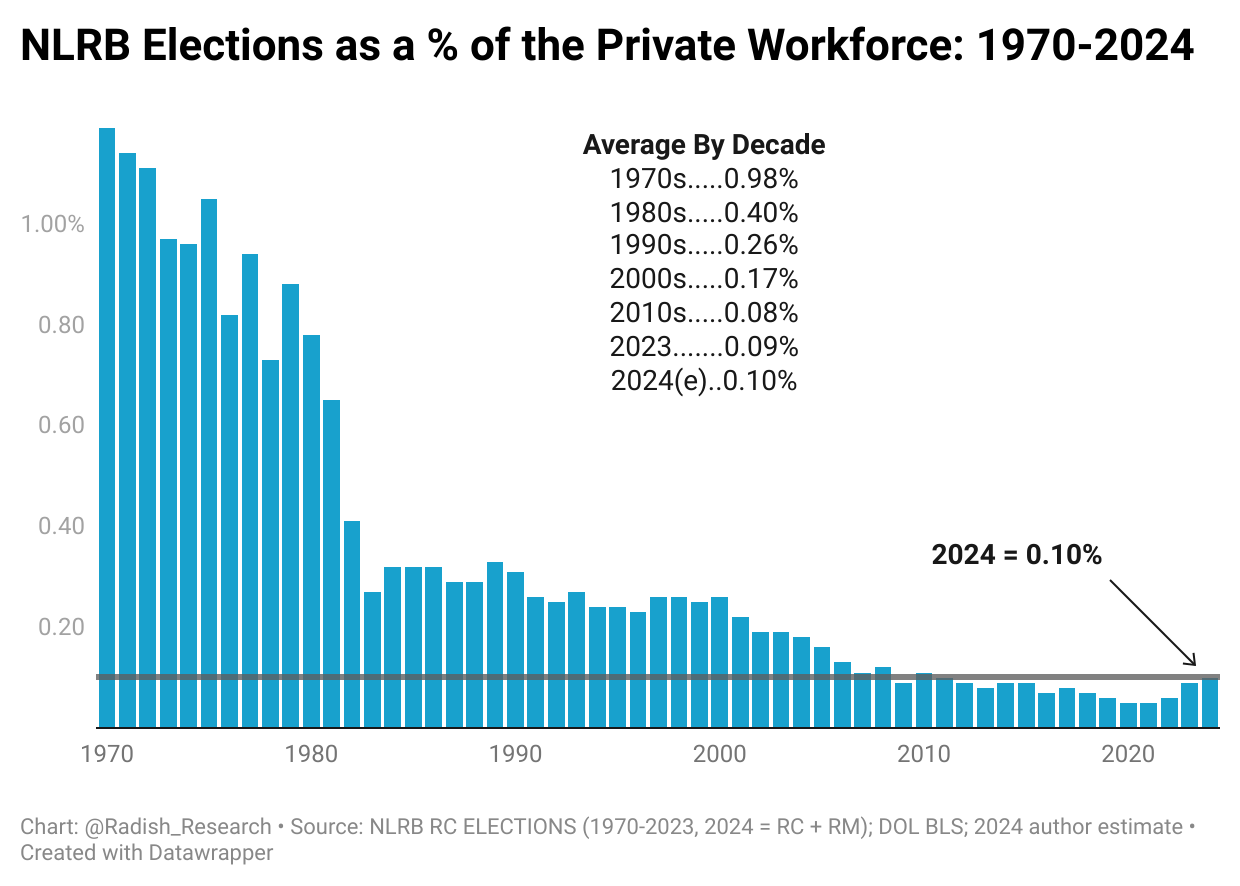

“We’re organizing like never before!” That’s what the AFL-CIO says, but is it accurate? While data is not readily available for public sector workers, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) tracks the number of workers involved in union elections in the private sector. In 2023, approximately 93,000 workers participated in an election for union representation, up from 63,000 workers in 2022. And 2024 is on pace for approximately 107,000 workers voting on union representation.1

The increase in union representation elections is encouraging, but if you step back and look at the number of elections in relation to total employment, the challenge becomes clearer. In 2023, the 93,000 workers participating in union elections represented just 0.09% of the 108.4 million production and nonsupervisory employees in the private sector. In 2024, the percentage is projected to be about 0.10% of all workers. In other words, only one-tenth of one percent of eligible U.S. workers in the private sector are getting the opportunity to vote for a union.2 This pace of organizing is not enough to keep up with employment growth, let alone meaningfully increase union density in the private sector (i.e. the percentage of all workers represented by a union).

Looking at the historical data, it’s harder to support the contention that labor is “organizing like never before.” The 2023-2024 election rate of 0.09-0.10% is just a smidge higher than the 2010 decade and significantly lags the average election rate of 0.17% in the 2000 decade.

But imagine if labor put on its seventies bell-bottom jeans and started organizing one percent of eligible workers as unions did in the 1970s, not the current one-tenth of one-percent rate. Instead of 107,000 workers voting for a union in 2024, the number would be more like 1.1 million workers.

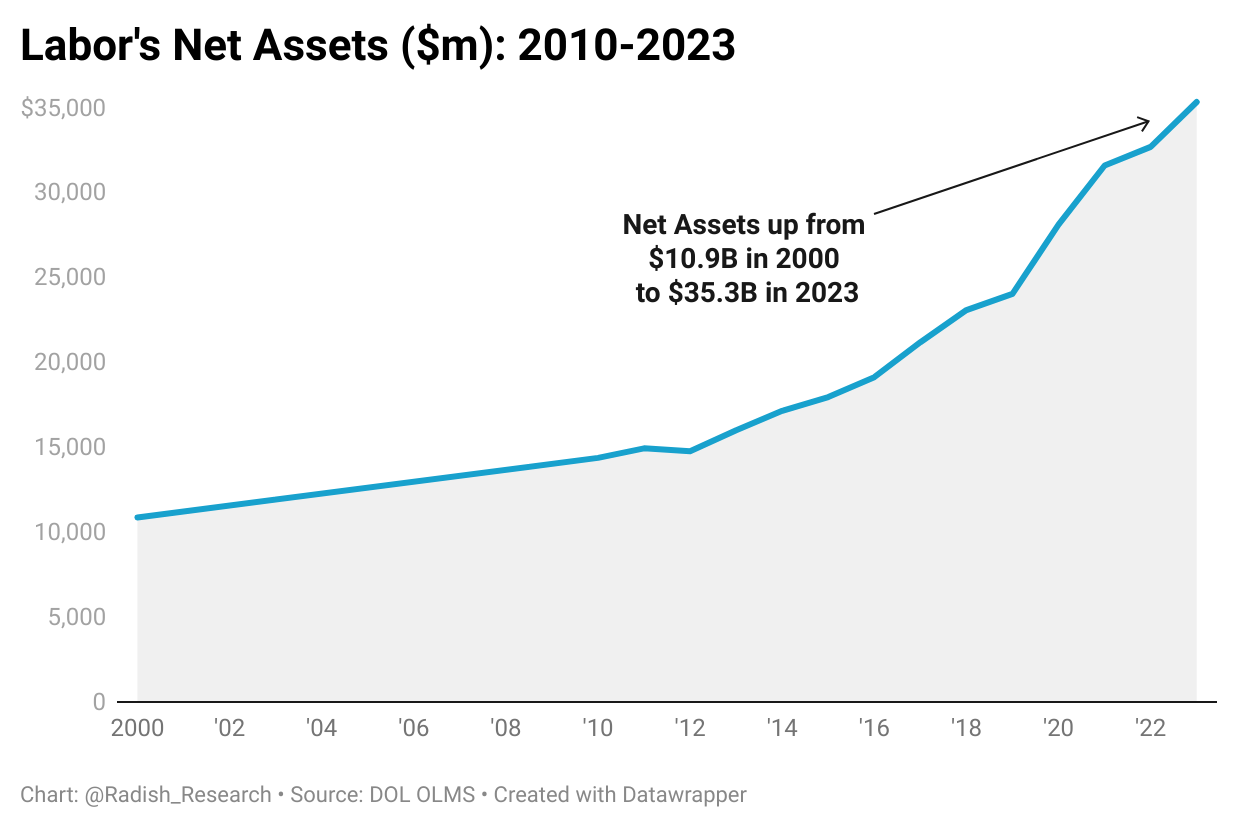

Why isn’t this happening, given the upsurge in worker interest in unions? It isn’t a funding issue, as labor has over $35 billion in net assets (see below). My take is that the existing labor leadership — many of whom have never committed to a robust organizing program to begin with — continue to believe that organizing is futile unless labor law is reformed. This entrenched belief is held even though unions are winning three-quarters of union elections under Biden’s revamped NLRB.

Secondarily, unions are justifiably worried about obtaining first contracts for newly organized workers (exhibit A: Starbucks) and concerned that the NLRB is too underfunded to process higher levels of worker petitions for elections. On the last point, the NLRB budget is currently about $300 million, but the agency says “we really need over $400 million.” The irony is labor has plenty of cash — $35 billion in net assets — to bridge the budget shortfall until Congress can pass appropriate funding.

According to the latest Gallup poll, approval of unions is at the highest level since the 1960s, yet only one-tenth of one percent of workers in the private sector got the chance to vote for a union. Labor should translate the popular support into action by pledging to give one million workers an opportunity to vote on union representation in 2025.

2. Strike Wave or Strike Blip?

Through June 2024, total compensation for union workers is up 6% year over year, while non-union workers have only seen a 3.6% increase over the same period. That’s the good news.

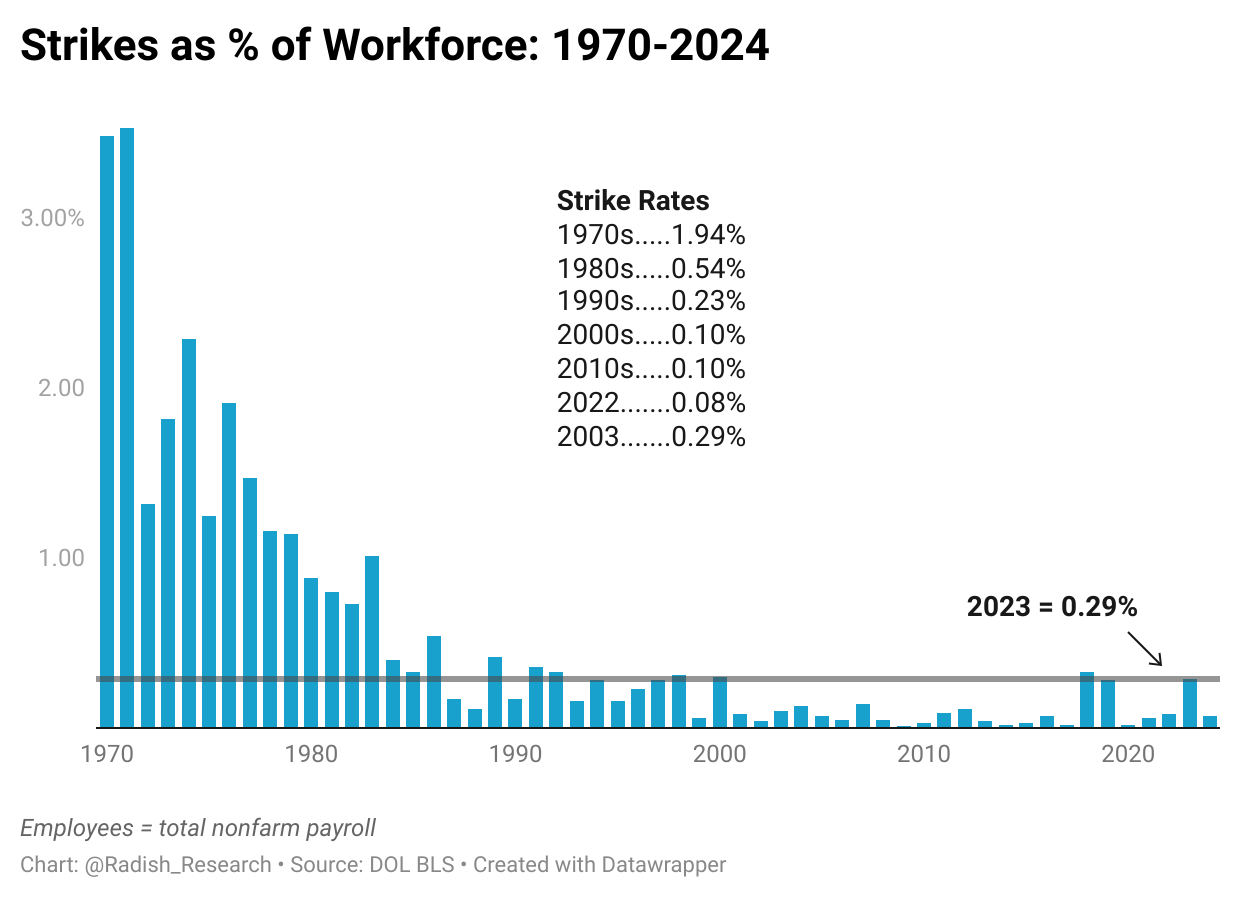

The disappointing news is the strike “wave” of 2023 appears to be a blip rather than an emerging trend. In 2023, approximately 459,000 workers went on strike, including 50,000 UAW members at the Big 3 automakers and 160,000 SAG-AFTRA members employed by the entertainment industry. Through late August 2024, approximately 106,000 workers have been on strike, significantly lagging the 2023 total strike numbers.3 While additional union contracts are expiring in the fall — most notably the Machinists and Boeing — it is likely that 2024 will fall short of the 2023 strike numbers.

Looking at strikes as a percentage of the non-farm workforce, the Red for Ed strikes of 2018-2019 and the 2023 strikes were the largest strikes dating back to 2000, representing about one-third of one percent of the total workforce. However, as with the organizing data, the 1970s were marked by a vastly higher proportion of workers on strike as a percentage of the workforce, reaching nearly two percent of all employees. If two percent of workers went on strike today, roughly 3.1 million would be picketing. Attending all of those picket lines would surely be a travel nightmare for the presidential candidates and faux populists rushing to attend.

3. Union Finances: “Up-Up and Away”

While the organizing and strike data are not breaking historical records, union finances are another story. As I’ve written here, here, and here, organized labor continues to amass a staggering cache of cash and investments. Net assets (assets minus liabilities) grew $2.6 billion in 2023, from $32.7 billion in 2022 to $35.3 billion in 2023. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Affairs, union dues are up $871 million as of June 2024, likely continuing the trend of asset growth in 2024.

While labor’s net assets have risen 225% since 2010, membership has declined by 1.8 million workers. I call this state of affairs Finance Unionism, where unions spend less on organizing and strikes than they bring in membership dues and investment income, investing the surplus in the financial markets.

No union has contested this data, and to my knowledge, no union has gone on record to explain the rationale for stockpiling assets rather than investing in organizing and strikes. Is any enterprising labor reporter in the house willing to ask the question (besides Hamilton Nolan)?

Union Democracy and Governance in 2024

Who makes the critical strategic decisions for organized labor? Who decides whether to invest union assets in the financial markets rather than organizing and strike activity? That would be the elected labor leadership. While the election of union leaders is formally democratic, the practice of union democracy is far from ideal.

As I’ve written here and here, the vast majority of top union officers are not directly elected by the members, and very few leaders face contested or competitive elections. In my view, the lack of substantive debate and member participation is a failure of democratic governance (for an alternative view, see this editorial). The 2024 conventions at some of the largest unions in the U.S. confirm this trend:

-

SEIU, 1,845,500 members: Mary Kay Henry stepped down in 2024 after serving fourteen years as president. April Verrett won the top position with 99.4% of the delegate vote. Many of the delegates to the convention were superdelegates — i.e., elected local officers who automatically became delegates without a membership vote.

-

American Federation of Teachers (AFT), 1,732,808 members. Randi Weingarten, the AFT President since 2008, was reelected to another term without any public opposition. Besides Douglas McCarron of the Carpenters (who has served for thirty years), Weingarten is the longest-tenured labor leader in the U.S.

-

AFSCME, 1,248,681 members: Lee Saunders, elected President in 2012, was reelected by the delegates by acclamation (i.e., no challenger) to another four-year term. By the end of his term, Saunders will have served for 16 years.

-

AFGE, 313,108 members: Everett Kelley, President of the union since 2020, faced a contested election at the convention, winning with 59% of the delegate vote.

-

UNITE HERE, 264,334 members: Taking over for President D. Taylor (my old boss), Gwen Mills was elected by delegates in an uncontested election.

-

Association of Flight Attendants (AFA-CWA), 45,500 members: Despite President Sara Nelson's endorsement of a resolution calling for direct elections of officers, the CWA-AFA Board of Directors voted against the constitutional change.

Of the large unions with a convention in 2024, only AFGE had a competitive election. The remaining unions — representing 5.1 million members and over a third of all union members — had no contested or competitive elections for the top leadership posts.

Labor Law Reform Version 4.0

With the relatively low organizing numbers and waning strike wave, what is the strategy of organized labor to reverse the decades-long decline? You won’t find any coherent plan outlined by the AFL-CIO, but it is the same strategy pursued for decades: reform labor law. It was the strategy of the 1990s (the Cesar Chavez Workplace Fairness Act), the strategy of 2008 (the Employee Free Choice Act), the strategy of 2020 (the Richard L. Trumka Protecting the Right to Organize Act), and it is the strategy of 2024.

Of course, labor law reform is vitally important, and it should be labor’s top legislative priority. But if Kamala Harris wins the Presidency, and if Democrats control Congress, Harris will have to overcome a certain filibuster in the Senate and wavering support from “moderate” Democrats facing unified opposition from employers. This is the traditional graveyard for labor law reform, but hopefully, a labor movement riding on a crest of popularity can transform the vibes into a legislative accomplishment.

The problem, however, is that labor’s legislative strategy has an expiration date. As long as labor’s share of the workforce continues to decline (5.8 million members lost since 1980 and counting), its political power also decreases. In 1980, one out of four voters was from a union household. In 2020, union households represented only 15.8% of voters.

Yes, organized labor should go all in for labor law reform, using every ounce of political capital to pass the legislation. To win, it will require subsuming the parochial political agendas of the sixty different unions to this one demand. But if the Democratic Party balks at reform as it has in the past, or if Trump wins a second term, then labor will need a backup plan. Ultimately, changing the political dynamic and forcing a new compromise between labor and capital will require unions to draw on their most potent source of power: workers withholding their labor and disrupting production and the economy.

Thanks for reading Radish Research! This post is public so feel free to share it. Subscribe to Radish Research.

1 Data on union elections are from the NLRB. Rather than report by calendar year, the NLRB reports election data on the federal fiscal year (October through September). The data only includes closed cases, and for the 1970-2023 period, only includes RC (representation elections) cases. Due to the NLRB’s Cemex decision, 2024 data includes RC and RM (employer-filed) petitions. Estimates for 2024 were derived by applying the 2024 increase year-to-date (19.6%) to August and September 2023 election closed cases. Total employees is derived from the Department of Labor’s Current Employment Statistics for Production and Nonsupervisory Employees in the private sector, seasonally adjusted

2 I learned about this methodology from Lane Windham’s excellent book Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide.

3 Data are from the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, which only tracks strikes involving 1,000 or more workers. The Cornell Labor Action Tracker endeavors to measure all strike activity, but it only tracks strikes from the last few years, so historical analysis is not possible. Total employee data are derived from the Department of Labor Current Employment Statistics release on total nonfarm payroll: “a measure of the number of U.S. workers in the economy that excludes proprietors, private household employees, unpaid volunteers, farm employees, and the unincorporated self-employed.”

Spread the word