Illinois Is the Last State Still Unlawfully Stripping Wealth From Homeowners in Tax Foreclosures

When Cook County sheriff’s deputies burst into the Maywood home of 74-year-old Velma Lewis with a battering ram, it wasn’t because she had committed a crime. Nor was there a warrant for her arrest.

It was because she’d fallen so far behind on her property taxes.

A decade ago, Lewis — whose mother bought the two-flat in 1961 and had long since paid it off — decided to replace her tattered roof instead of paying $6,200 in property taxes.

After she failed to pay the taxes for another nine months, Cook County officials auctioned off her tax debt to a private investor, as required under Illinois law.

Retired and living on a fixed income, Lewis says she was saving to get current on her taxes but fell even further behind.

The investor foreclosed on Lewis’ home, and, three years later, sheriff’s deputies showed up at her front door.

“They told me I had to get out, and they were searching the house, asking me did I have any guns, and ‘If you got any medicine, get your medicine,’ ” Lewis says.

Velma Lewis had to buy back her Maywood home from an investor who bought it at a property tax foreclosure sale. Abel Uribe for Injustice Watch

The investor who paid off her delinquent property taxes took the deed to Lewis’ home, which was worth around $180,000.

Lewis walked away with nothing.

“I can’t dwell on it too long ’cause it’ll make me cry,” she says.

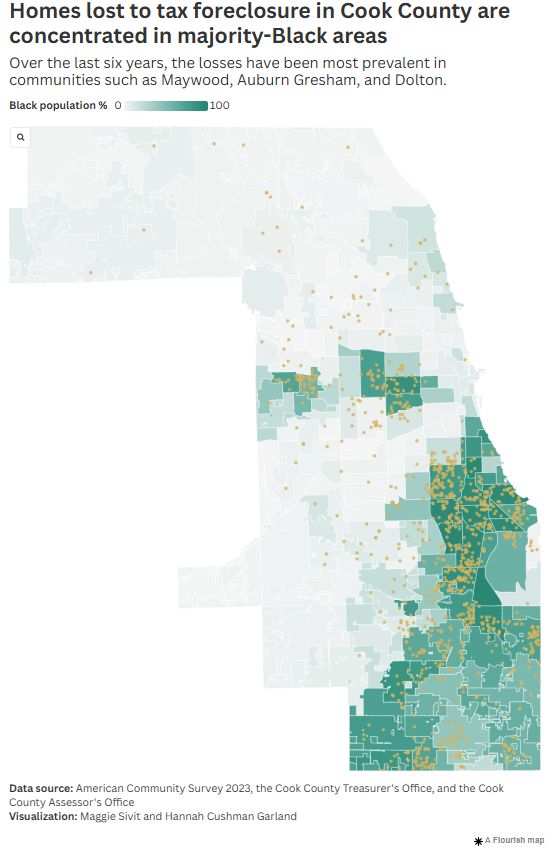

For decades, homeowners in predominantly Black neighborhoods across Cook County have lost homes the way Lewis did — over unpaid property taxes, an investigation by the Investigative Project on Race and Equity and Injustice Watch has found.

Some say they fell behind after losing a job, others because of emergency expenses or debilitating health issues like Alzheimer’s disease. Some just couldn’t keep up.

Since 2019, more than 1,000 owner-occupied homes in Cook County — including more than 125 homes owned by older people — were taken through property tax foreclosure, the news organizations found.

Illinois is the only state that hasn’t adopted reforms aimed at giving homeowners who lose their homes this way their fair share of the tax sale proceeds.

While owner-occupied homes lost to tax foreclosure represent only a tiny fraction of Cook County’s 1.5 million residential properties, they are highly concentrated in predominantly Black communities like Roseland and Englewood in the city of Chicago and in Chicago Heights, records show.

More than half of all homes lost this way were taken after an initial property tax debt of $1,600 or less, records show. A dozen started out owing less than $200.

Collectively, the initial debt that cost people their homes totaled $2.3 million. But an analysis of Cook County assessment data shows these homes have a combined estimated market value of more than $108 million.

All of the equity tied up in their homes — which, as with Lewis, often was built over generations — went largely to a small network of private investors who took over the deeds after paying the delinquent property taxes.

This massive transfer of generational wealth from families in Black neighborhoods to affluent investors has long been criticized by housing advocates and civil rights leaders as a racist practice that has drained wealth from Black Americans since they came to Chicago from the Jim Crow South in pursuit of the American dream, including homeownership.

Two years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously decided in a Minnesota case that the practice violated what’s known as the takings clause in the Bill of Rights.

Kileen Lindgren, a legal policy manager for Pacific Legal Foundation, which argued that case for the homeowner, says Illinois’ tax sale policy is the “most abusive property tax forfeiture system” in the country.

“The court ruled the government could take what it was owed and no more, but Illinois keeps taking,” she says. “They’re clinging to a system that just isn’t protecting people.”

For decades, civil rights leaders have tried to persuade Illinois lawmakers to eliminate or limit the power of third-party investors, and following a tax foreclosure, give homeowners their fair share of the equity they’d built up.

They were blocked by investors — tax buyers — and their lobbyists.

Tax buyers even helped write the laws that send millions of dollars their way.

“These very industries are preying upon people who are already facing extreme hardships because there’s money to be made off of them,” says Andrew Kahrl, a University of Virginia historian and author of the book “The Black Tax,” published last year, on the tax lien industry and its impact on Black communities in Chicago and across the country. “It’s really disturbing in its own respect. But it’s even more disturbing when we recognize that our local governments are actually willing partners in these schemes.”

A half-dozen of the most active tax buyers and their attorneys declined interview requests.

Representatives of the tax buyers’ lobby groups say they were invited by lawmakers to more quickly recover tax revenue to fund services like public schools.

“Does it benefit the local government? The answer is yes,” says Brad Westover, executive director of the National Tax Lien Association, “because the government receives the funds that they were owed so they could still pay the police and the fire and the public schools and still cut the lawns at the local park and still build the roads and bridges.”

The Supreme Court ruling has spawned lawsuits by homeowners throughout Illinois and reinvigorated critics who want lawmakers to reconsider reform efforts.

Measures now in Springfield seek to address the Illinois tax foreclosure system and provide for homeowners to get back at least some of the money they are owed. None of the proposals would eliminate the involvement of the third-party players.

Gov. JB Pritzker, who has touted his record on racial equity, declined an interview request.

His spokesperson says Illinois is in compliance with the Supreme Court ruling, though some Democratic lawmakers pushing for reforms — as well as legal experts — disagree.

“I believe, and I think that many others in this space believe, that Illinois’ current tax sale system is out of compliance,” says state Rep. Will Guzzardi, D-Chicago. “That puts us in real legal liability. The right thing to do is to make sure that homeowners get as much of their equity as they can at the end of this process. And our current system doesn’t do that.”

‘Jail or … take their property’

Illinois legislators created the tax foreclosure system in 1951, at the height of the Second Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans left the South for economic opportunities in the North.

The law — drafted with input from tax buyer Allan Blair — made it more profitable for investors to foreclose after buying tax liens throughout the state. It allowed Blair and other tax buyers to take full ownership of properties when taxpayers did not pay off a delinquent tax bill within two years.

“There are only two ways you can handle delinquent taxpayers,” Blair told the Chicago Tribune in 1974 — five years before he died — about the law he helped draft. “You can put them in jail, or you can take their property away. Now, I ask you which is better?”

Even as news stories and columns shined a light on cases of mostly older, widowed and homeowners with disabilities who lost homes under the system, lawyers argued in court that the law could be unfair even to homeowners who understood the consequences of falling behind on their taxes.

In 1969, homeowners’ attorney Marshall Patner likened one case to sentencing “a man to death for stealing a loaf of bread” by taking his home over such a small debt, Kahrl says in his book.

By 1970, outrage spurred lawmakers to create a special fund to compensate some homeowners who lost their homes to tax foreclosure.

But this “indemnity fund” was filled with obstacles, and few homeowners took advantage. To be eligible for a payout, homeowners had to sue the county and prove they had legitimate reasons for not paying their taxes, such as a family emergency or other hardship.

While the 1951 law opened the door for a massive transfer of wealth to the investors, a 1970 change of language in the state constitution effectively guaranteed a place at the table for tax buyers. Legal experts say removing tax buyers today from the process would require a constitutional amendment, an expensive and time-consuming process.

In 1976, a legislative commission condemned the “unnecessary harshness” of the law, writing, “The only function of total forfeiture is the enrichment of tax buyers at the expense of a very few tragic victims.”

It recommended that, rather than rely on the underutilized indemnity fund, the state should introduce an auction process to guarantee the return of at least some equity to all homeowners.

But lawmakers didn’t implement the proposals.

Attempts at reforms continued over the next 50 years, targeting the foreclosure process and the high interest rates tax buyers charge homeowners. But most fell short.

The indemnity fund remained the main source of relief for homeowners. Decades later, the fund is insolvent. The few homeowners who are approved for payouts have to wait years to see any money, the Illinois Answers Project reported in 2022.

Between 2016 and 2024, the bulk of the fund’s money was signed over in advance to investors, Cook County treasurer’s office data shows.

A landmark ruling

In 2023, a case involving an older Minnesota homeowner who lost her home under similar circumstances to what happened to Lewis became a landmark Supreme Court decision that guarantees homeowners their fair share in tax foreclosure cases.

The 9-0 ruling found that Minnesota’s practice of selling homes for unpaid tax debt and pocketing the difference violated the Fifth Amendment’s takings clause, which bars governments from taking private property without just compensation.

“A taxpayer who loses her $40,000 house to the state to fulfill a $15,000 tax debt has made a far greater contribution to the public than she owed,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the decision. “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more.”

More than a dozen state legislatures have passed reforms since the Minnesota ruling, though not Illinois.

The history of failed reforms to the Illinois tax sale system

Over the decades, many efforts to protect homeowners from losing their homes and equity to tax foreclosure have fallen short.

Illinois tax sale system established

1872

The Illinois Revenue Act of 1872 permits investors, known as tax buyers, to purchase property tax liens when tax bills go unpaid. But the law prevents investors from obtaining a clear title.

Government strengthens foreclosure powers for private tax buyers

1951

A new law, signed by Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson, allows private investors to take full ownership of a property when the homeowner cannot pay off a delinquent tax lien. The law is drafted in part by Allan Blair, a powerful Chicago lawyer and real estate investor. The law invites more speculators to buy tax liens at the annual auctions.

Proposal attacks ‘tax vultures’

1963

After a homeowner in Chicago’s Austin neighborhood loses a home to a private investor over a tax bill of around $900, there is a public backlash. Critics propose legislation to eliminate profiteering “tax vultures” from the process. Under the plan, counties would handle tax foreclosures and collection, and any profits from the sale of a home after the debt is satisfied would be returned to the homeowner. The bill ultimately fails.

Bills to give homeowners access to equity fail

1969

Illinois legislators, including Rep. Harold Washington and Sen. Richard Newhouse, again propose the elimination of tax buyers from the foreclosure process. Under their bill, government officials would handle all property tax foreclosures. Following the sale of a home at auction, net proceeds would be returned to the former homeowner. Again, the proposal ultimately fails.

Lawsuit challenges legality of tax sale

1969

Attorneys representing West Side homeowners Louis and Doretta Balthazar argue Illinois’ tax sale law unconstitutionally and unfairly deprives homeowners of their homes. The case goes to the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal, but justices agree with the district court, ruling the statute may be “oppressive” but is not unconstitutional. The Balthazars lose their home to Allan Blair, the tax buyer who helped write the 1951 law. Ultimately, the Balthazars buy back their home.

Outcry grows over impacts of lost homes

1969 — 1979

Over the course of a decade, newspapers publish dozens of articles scrutinizing the practices of private tax buyers, highlighting the impacts of tax sales and tax foreclosures on Illinois homeowners — especially senior homeowners. Op-ed writers suggest weak laws and apathetic lawmakers are ultimately responsible for the lost generational wealth.

Legislators create ‘indemnity fund’

1970

Reacting to prolonged criticism of the tax foreclosure system, Illinois lawmakers establish a fund they say will help some homeowners recoup a portion of their homes’ value following tax foreclosures. However, advocates argue the obstacles to receive a payout from the so-called “indemnity fund” are often prohibitive and unfair. Homeowners must file a lawsuit and prove their taxes were unpaid through “no fault of their own.”

Evanston resident loses her home — and buys it back

1971 — 1974

A high-profile case involving Lillian Ware — who lost her Evanston bungalow to tax buyer Allan Blair over a tax bill of around $40 — winds its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Her attorney argues it was unfair for Blair to take her home. The high court rules against Ware, but the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People helps her buy back her home.

State legislative commission urges reforms

1976

After the Lillian Ware case, the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission issues a report condemning the state’s tax foreclosure law and calling for revisions to give homeowners proceeds from tax sales. Again, the recommendations go nowhere.

County official files tax sale lawsuit

1998

South Side homeowner Mary Lowe is hospitalized, and doesn’t receive notices her tax debt was sold. The home goes into foreclosure. The court-appointed Cook County Office of the Public Guardian files a case on her behalf. The U.S. Supreme Court finds her rights were violated. However, the Illinois Supreme Court declines to revisit its earlier decision. The Lowe family loses their home.

Pappas encourages competition among tax buyers

1998 — 2000

Newly elected Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas — whose office oversees tax lien auctions — adopts a new policy aimed at preventing collusion among private investors, who she suspects are working together to maximize interest rates they charge property owners after purchasing delinquent taxes. The policy is challenged by the tax buyer lobby, but the Illinois Supreme Court rules in favor of Pappas.

Jesse Jackson weighs in on senior foreclosures

2000

Jesse Jackson of the Rainbow PUSH Coalition urges Illinois lawmakers to change tax sale law to protect senior homeowners. He speaks out following media reports of a 76-year-old widow who lost her West Side home to tax foreclosure. Although Jackson works with Cook County officials to ensure the woman stays in her home, his calls for more sweeping reforms go nowhere.

Bill to protect homeowners with disabilities fails

2004 — 2005

A proposal to help homeowners with disabilities get legal representation from the Office of Public Guardian in tax foreclosure cases passes the Illinois Senate. The bill dies in the House.

Bill to enhance homeowners’ rights in tax foreclosure cases fails

2007

A proposal to require tax buyers to send additional legal notices about upcoming foreclosures and to give homeowners more standing to request judges stop the transfer of their deeds fails in the Illinois Senate.

Another bill to protect homeowners with disabilities fails

2010

Another bill seeks to exempt homeowners with disabilities from tax sales. The bill, one of several tax sale reforms supported by the Cook County Public Guardian and filed by State Sen. Ira Silverstein, a Chicago Democrat, dies in the Senate without a vote on the floor.Legislators cut interest rates on delinquent bills

Legislators cut interest rates on delinquent bills

May 24, 2023

Illinois legislators pass a law to halve interest rates charged by the county on delinquent tax bills, from 18% to 9%. The measure — supported by Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas — also closes loopholes used by tax buyers to collect hundreds of millions in refunds from the county on their investments.

Tyler v. Hennepin County

May 25, 2023

The U.S. Supreme Court rules unanimously Minnesota’s policy of taking homes in tax foreclosure over a tax debt violates the “takings clause” in the Bill of Rights. “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more,” writes Chief Justice Roberts in the landmark decision. The ruling prompts states throughout the nation to reform tax foreclosure statutes.

Pappas proposes cutting out tax buyers

October 30, 2023

Despite the Supreme Court ruling in Tyler v. Hennepin County, Illinois does not create a practical way for homeowners to receive equity after tax foreclosure. In meetings with lawmakers, a top official for Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas presents the benefits of cutting out private investors from the tax foreclosure process. The proposal goes nowhere.

Lawmakers consider ways to address access to equity

2025

Illinois remains the last state to comply with the 2023 Supreme Court decision. State lawmakers make several proposals to financially help homeowners in tax foreclosure cases, but none of the measures include removing the third-party profiteers — tax buyers — from the process.

“There are only two ways you can handle delinquent taxpayers,” Blair told the Chicago Tribune in 1974 — five years before he died — about the law he helped draft. “You can put them in jail, or you can take their property away. Now, I ask you which is better?”

Even as news stories and columns shined a light on cases of mostly older, widowed and homeowners with disabilities who lost homes under the system, lawyers argued in court that the law could be unfair even to homeowners who understood the consequences of falling behind on their taxes.

In 1969, homeowners’ attorney Marshall Patner likened one case to sentencing “a man to death for stealing a loaf of bread” by taking his home over such a small debt, Kahrl says in his book.

By 1970, outrage spurred lawmakers to create a special fund to compensate some homeowners who lost their homes to tax foreclosure.

But this “indemnity fund” was filled with obstacles, and few homeowners took advantage. To be eligible for a payout, homeowners had to sue the county and prove they had legitimate reasons for not paying their taxes, such as a family emergency or other hardship.

While the 1951 law opened the door for a massive transfer of wealth to the investors, a 1970 change of language in the state constitution effectively guaranteed a place at the table for tax buyers. Legal experts say removing tax buyers today from the process would require a constitutional amendment, an expensive and time-consuming process.

In 1976, a legislative commission condemned the “unnecessary harshness” of the law, writing, “The only function of total forfeiture is the enrichment of tax buyers at the expense of a very few tragic victims.”

It recommended that, rather than rely on the underutilized indemnity fund, the state should introduce an auction process to guarantee the return of at least some equity to all homeowners.

But lawmakers didn’t implement the proposals.

Attempts at reforms continued over the next 50 years, targeting the foreclosure process and the high interest rates tax buyers charge homeowners. But most fell short.

The indemnity fund remained the main source of relief for homeowners. Decades later, the fund is insolvent. The few homeowners who are approved for payouts have to wait years to see any money, the Illinois Answers Project reported in 2022.

Between 2016 and 2024, the bulk of the fund’s money was signed over in advance to investors, Cook County treasurer’s office data shows.

A landmark ruling

In 2023, a case involving an older Minnesota homeowner who lost her home under similar circumstances to what happened to Lewis became a landmark Supreme Court decision that guarantees homeowners their fair share in tax foreclosure cases.

The 9-0 ruling found that Minnesota’s practice of selling homes for unpaid tax debt and pocketing the difference violated the Fifth Amendment’s takings clause, which bars governments from taking private property without just compensation.

“A taxpayer who loses her $40,000 house to the state to fulfill a $15,000 tax debt has made a far greater contribution to the public than she owed,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the decision. “The taxpayer must render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, but no more.”

More than a dozen state legislatures have passed reforms since the Minnesota ruling, though not Illinois.

“Illinois isn’t even at the constitutional bare minimum floor right now,” says Cook County Public Guardian Charles Golbert, whose office represents homeowners with disabilities who are facing tax foreclosure.

“Illinois isn’t even at the constitutional bare minimum floor right now,” says Cook County Public Guardian Charles Golbert, whose office represents homeowners with disabilities who are facing tax foreclosure. Ashlee Rezin / Sun-Times

The Minnesota ruling spawned lawsuits in state and federal courts filed by former Illinois homeowners seeking to recover their lost home equity.

In court filings, county officials have argued that they can’t repay homeowners because tax buyers were the ones who sold their homes and collected their equity. And the tax buyers say it’s up to the government to make former homeowners whole.

The real culprit, legal experts say, is the state’s property tax code, which mandates the sale of delinquent taxes to private investors but doesn’t provide homeowners a meaningful way to access their home equity if they lose a home to tax foreclosure.

In court filings, officials from seven collar counties argue that the property tax code compels them “to violate the former property owners’ constitutional rights with no mechanism to alleviate the violations.”

To protect homeowners from foreclosure, taxing authorities in Philadelphia, Milwaukee and the state of Maryland have taken steps to create more robust payment plan options and to make tax sale notices easier to understand.

In 2011, New York City exempted the most vulnerable homeowners — including older people and people with disabilities — from tax foreclosures.

Starting five years ago, Baltimore officials have removed all owner-occupied homes from tax sales.

“It would be fantastic if, in the process of coming up to the bare minimum of what the Constitution requires, Illinois will follow the leads of other states and actually provide an even higher level of protection for some of the most vulnerable homeowners,” says Golbert, whose office has lobbied unsuccessfully for homeowners with cognitive disabilities to be exempted from tax sales.

Buried in tax debt

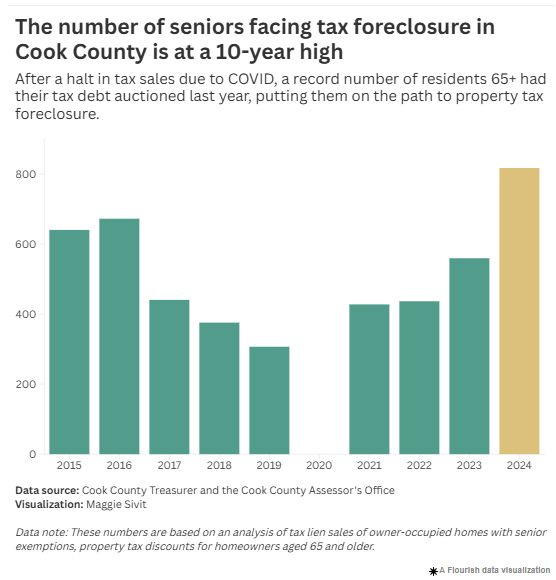

Under the tax lien system, Cook County’s most vulnerable homeowners, especially older people, can quickly become buried debt. Once a tax buyer purchases a tax lien at auction, the balance grows quickly, with fees and interest tacked on, especially if homeowners miss another tax payment.

Diana Nesbitt missed the second of two tax installments in 2016, totaling $1,483. Then, she was late paying her first installment of $6,244 in 2017.

It took Nesbitt, who’s 69 and a cancer survivor raising her teenage granddaughter, two years to pay off the debt. She says she ended her retirement and went back to work to do that.

She remembers the relief when she made the payment just before New Year’s 2020.

“This is the only home she knows,” Nesbitt says of her granddaughter. “I can’t let them take it away from her, from us.”

Nesbitt paid more than $1,532 in investor fees and $1,694 in interest, records show.

Tax buyers appear to be particularly attracted to tax bills faced by older homeowners, the Investigative Project and Injustice Watch found.

On average, tax buyers paid for more than 1 in every 4 liens listed for sale in the last decade. But they gobbled up the bill of nearly every older homeowner — roughly 96% — who wound up in the tax sale during that period, tax sale records show.

Last year, more than 800 older homeowners had their tax debt sold at auction — the most in a decade. Collectively, they owed $2.3 million — about 0.01% of the county’s $17.6 billion property tax levy in 2022, the year the delinquent taxes were due.

In recent years, lawmakers have taken some steps to reduce the costs the government can pass on to homeowners. In 2023, they cut in half the interest rates for paying overdue property taxes.

But proposals to cut tax buyers out of the process altogether — which, proponents argue, would result in homeowners having to pay less in interest and fees to avoid foreclosure — have gone nowhere.

Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas, who backs the proposals, says “it’s maddening” that lawmakers haven’t passed greater reform. She blames tax buyers: “Their phalanx of well-paid lobbyists is doing all it can in Springfield to block the sensible reforms that we’re trying to make.”

Tax buyers’ most prominent lobbyist in Springfield — former Illinois state Rep. Michael J. Zalewski, a fixture on the Southwest Side political scene who chaired the Legislature’s Revenue and Finance Committee for six years, until 2023 — declined an interview request.

Buying the same house twice

It’s been almost three years since sheriff’s deputies evicted Velma Lewis at the request of tax buyer Greg Bingham of Northlake, who has bought thousands of tax liens worth tens of millions of dollars, according to tax sale and corporate records.

Bingham offered to sell Lewis the home that she inherited, free and clear, after her mother died in 2008. The price tag: $180,000. She decided to take on debt to get the home back.

“My mother bought that place,” Lewis says. “She worked hard. She worked two jobs.”

So, in 2023, Lewis took out a 30-year mortgage to buy back the home where she grew up.

But the home inspection required for the sale found 88 code violations, from electrical wiring issues to missing plumbing fixtures.

“Neighbors in the area had broken in and stolen a lot of contents from the building,” Bingham says.

So Lewis is also responsible for $80,000 of repairs that Maywood village inspectors required.

Now 77, she says she’s paying the bills with help from family members and getting by on her monthly Social Security check but is happy she managed to keep her mother’s house.

Still, Lewis wishes she had known better from the start how the tax sale system works. She also wants state and county officials to better inform homeowners what can happen when they miss a payment.

There “should be a way that they can work it out, where you don’t lose your house, you know,” Lewis says. “There’s these hound dogs out here that are going to take it if they can.

“This man would have took mine. But it’s just that I didn’t want to give it up.”

Contributing: Tatiana Walk-Morris, Maia McDonald, Kristen Axtman.

Investigative Reporter Emeline Posner is a Chicago-based freelance writer and copy editor whose reporting on city land use, the U.S. census and maternal health has appeared in the Chicago Reader, Chicago Magazine, South Side Weekly, Block Club Chicago and In These Times. Posner earned a master’s in journalism from Medill at Northwestern University, with a concentration in investigative reporting and a bachelor’s degree in classical studies from the University of Chicago.

Carlos Ballesteros reports on incarceration, policing, and issues affecting immigrants and older adults in the court system. Before joining Injustice Watch in 2020, Carlos was a Report for America corps member at the Chicago Sun-Times and a breaking news reporter at Newsweek in New York.

Vital Chicago news relies on you

The mission of the Sun-Times team -- reporters, photographers, editors -- is to bring you stories every day about the Chicago area. That's news, features and sports, from pro to prep. As the only Washington Bureau Chief from a Chicago news outlet, my priority in DC is to report on government and political news with a Chicago angle. In order for the Sun-Times to continue delivering our journalism, our operation has to be financially viable. As a community-funded nonprofit newsroom, we rely on your support to continue our vital work. Please consider making a donation to help sustain our newsroom and the important stories we bring to you.

Lynn Sweet

Washington Bureau Chief

Spread the word