INTRODUCTION BY NATIONAL SECURITY ARCHIVE

Washington, D.C., May 22, 2025 - Early in the morning of October 7, 1963, the top leadership of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) gathered in the office of the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) to discuss the brewing crisis in South Vietnam and America’s role in it. DCI John McCone warned his colleagues: “Under no circumstances” should “the Agency get into the subject of assassination or other highly sensitive matters with [U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot] Lodge.” The Ambassador had “no concept of security,” McCone added, and tended to use the press to enhance his power, presumably at the expense of the CIA, according to a recently declassified account of the meeting published today by the National Security Archive (Document 9). Twenty-six days later, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, were executed as part of a military coup d’état that would further destabilize the Southeast Asian country for years to come.

In the years since, the extent of the U.S. role in the coup and assassination has been hotly debated and disputed. For over two decades, the late John Prados shed light on the Kennedy administration’s position toward the Diem coup in a series of National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Books. This new EBB supplements those publications with recently declassified documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), the JFK Assassination Files, the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, and the personal papers of George McTurnan Kahin, a prominent scholar on Southeast Asia and early critic of the Vietnam war. It highlights the role of key CIA players—McCone, CIA Far East Division Chief William Colby, CIA Saigon Chief of Station John H. Richardson, and contract officer Lucien Conein—and provides new details on how the coup emerged, almost organically, despite indecision, divisions between the leading agencies, and bitter rivalries among the individual officials in charge. With Colby and McCone opposed to the coup, Conein, who was trusted by Lodge and keen to follow the Ambassador’s orders, became the key player on the ground.

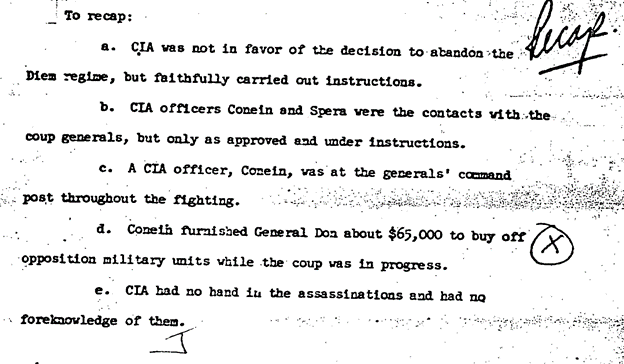

From the very beginning, government secrecy, obfuscation, lies, and the incomplete and contradictory statements of key American participants confused the record. Less than two weeks after the coup against Diem, and on the day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, McCone—joined by Colby—told the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) that the CIA “had no part in organizing the coup” and “did not have information on and does not know about the assassinations of Diem and Nhu,” according to a document that was fully declassified for the first time this year as part of the final JFK assassination documents release (Document 18). Yet a dozen years later, Colby, then the DCI and speaking to congressional investigators, expressed a more introspective tone and acknowledged the Agency role: “I think when you support a coup through violent overthrow you have to understand that you are taking responsibility for people getting killed. Soldiers got killed and the head of the other side got killed.” Additional documents declassified last year under the FOIA, including a detailed CIA chronology of the entire episode, show that the U.S. encouraged the coup plotters to take “the earliest possible action” and provided assurances, money and other support that together “constituted a clear call for action” (Documents 7 and 19).

By the late summer of 1963, as meetings between the CIA’s Lucien Conein and the plotting South Vietnamese Generals continued, Washington had settled, based on Ambassador Lodge’s recommendations, on a position of “not thwarting” a coup, according to a document released earlier this year in response to a FOIA request from the National Security Archive (Document 8). Langley also instructed Conein to review the Generals’ plans, with the exclusion of any assassination plots. The U.S. also promised that military aid would continue once the Generals had removed the Diem regime. Caught off guard as the coup started, having received a much shorter warning than anticipated, Conein handed over the rough equivalent of $68,000 in bribes “to reward opposition military units who joined the coup group,” according to a now declassified report from the CIA Inspector General (Document 19), and sent frequent reports to Saigon and Langley from the Generals’ headquarters (Document 17).

Document 19 – Fully declassified CIA Inspector General report provides new details on U.S. government role in coup against Diem

This newly available historical evidence shows that the U.S. was deeply involved with the key players who would ultimately overthrow and kill Diem and his brother, up to and including the day of the coup. While Colby and McCone were clearly opposed to the coup and made the strongest arguments against it, the senior CIA officials were overruled by the President and outmaneuvered by Lodge. In the end, they and their CIA colleagues “faithfully carried out instructions” to support the coup-plotting generals, according to a long-awaited and now fully declassified CIA Inspector General report on the episode (Document 19).

Other notable documents published today include:

- An August 30 telegram from a CIA Saigon Station officer (likely Conein) reporting on an explicit discussion among the coup-plotting South Vietnamese Generals about the need to assassinate President Diem for the success of the regime-change operation (Document 3).

- Reports providing additional details on Langley’s initial reluctance to overthrow Diem—partly due to the Agency’s long-standing relationship with his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu (Documents 4, 6, and 13).

- Documents showing that the U.S. Embassy in Saigon was mired in dysfunction and mistrust, with Lodge blaming CIA Chief of Station John Richardson for the August coup failure and Richardson finding Lodge too gung-ho and untrustworthy (Documents 6 and 7).

- Records on McCone and Colby’s growing distrust of, and contempt for, Ambassador Lodge, culminating in their failed opposition to replacing Richardson as CIA Chief of Station (Document 9).

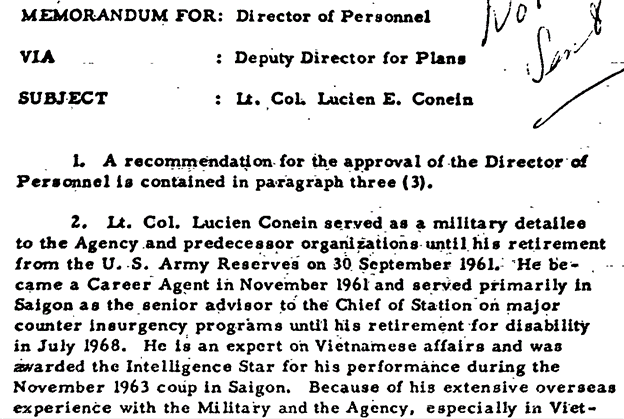

- The fully declassified CIA personnel file on Lucien Conein—who would be awarded the CIA’s “intelligence star” for his efforts during the South Vietnamese crisis of 1963—suggests he played a more prominent role than previously acknowledged (Document 22).

-

A document found among the personal papers of George McTurnan Kahin suggesting a new version of—and a new rationale for—the South Vietnamese Generals’ decision to murder Diem and Nhu: that if they survived, Washington might change its mind and reinstate them in power (Document 23).

Briefing book by Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi and Luca Trenta

When the U.S. government desires the overthrow of a foreign government, the ideal scenario for policymakers is that the U.S. plays a minimal, deniable role, and that the government speaks with one voice. Part of the challenge in ascertaining the degree of U.S. involvement in the overthrow and assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem—aside from secrecy—is the fact that the Kennedy administration’s position toward the South Vietnamese president in the summer and fall of 1963 was marked by division, indecision, oscillation, distrust, and bureaucratic chicanery.

The failed August coup

In retrospect, the fate of Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, was sealed during the “Buddhist Crisis” of May 1963. On June 11, the images of the self-immolation of Buddhist Monk Thích Quang Duc in the name of religious freedom shocked the world and focused attention—including in Washington, D.C.—on the autocratic, repressive, unstable, and corrupt nature of Diem’s regime. Diem and Nhu—the head of South Vietnam’s secret police—began to be perceived as incapable of leading a united South Vietnam against the communist threat. By August 1963, several U.S. officials had become so disgruntled with Diem, especially in the White House and State Department, that they began taking formal steps to create the conditions for a coup.

On August 24, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Roger A. Hilsman sent a now-infamous State Department Telegram (DepTel) No. 243 to Saigon (first published in National Security Archive EBB 302 of 2009). DepTel 243 asked the Embassy to make clear to the Vietnamese military that the U.S. would support a new interim government. The Ambassador and the Country Team were asked to “urgently examine alternative leadership” and to make “detailed plans” on how to “bring about Diem’s replacement if this should become necessary” (Document 19). Two documents now confirm that the CIA played no role in drafting DepTel 243 and was not consulted during the decision-making process. Instead, Deputy Director for Plans Richard Helms was only notified of the DepTel once it had been cleared with “Hyannis Port,” that is, with President Kennedy (Documents 16 and 19). In Saigon, CIA Chief of Station John Richardson later reported that Lodge interpreted the telegram as marching orders to orchestrate a coup (Document 9).

Two days later, a CIA station telegram that was probably responsive to instructions from Washington further specified the position that the Embassy and the station would take in their dealings with the coup plotters. Ambassador Lodge said the operation should be deniable; the U.S. hand should not show. The telegram also contained nine points to guide the Country Team’s approach to the generals. These included an agreement that Nhu had to go but also that the fate of Diem was up to the generals themselves. The document confirmed the U.S. posture of deniability, telling the Generals: “Win or Lose. Don’t expect to be bailed out.” And yet, it also sets a clear system of incentives for the Generals to proceed: Unless the Nhus were removed from power and the Buddhists were freed, the Generals could expect an end to financial and military support (Document 1).

As the CIA team was getting ready to meet the Generals based on these guidelines, the situation changed on the August 29. In the morning, CIA Chief of Station Richardson, CIA contract agent Lucien Conein, and CIA station officer Alphonse Spera were shown a telegram from General Maxwell Taylor to Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) Commander Paul Harkins. The telegram hinted that Washington had “second thoughts” regarding the coup (Document 7). With a meeting with the Generals already scheduled, Richardson ordered Conein and Spera to proceed but to provide no iron-clad assurances regarding U.S. support. Having met with the Generals, the CIA reported to Washington that they had a “plan for a coup d’etat and will implement it when they are assured that the US government is fully behind them.” As proof of support, the Generals asked the U.S. to cut aid to the South Vietnamese government. The suspension of aid would signal U.S. support and alter the balance of forces in Saigon against Diem.

On the 30th, an exchange between the President and Lodge made clear that—while Washington had not completely changed its mind on a coup—Kennedy wanted to keep his options open until the last minute and support a coup only if it would be successful. As he told Lodge, “When we go, we must go to win, but it will be better to change our minds than to fail.” Lodge agreed with the President but also warned that—since this was primarily a Vietnamese affair—the U.S. government might not have the option to stop the coup once one was in motion.

Document 3 – South Vietnamese Generals openly discuss assassinating Diem.

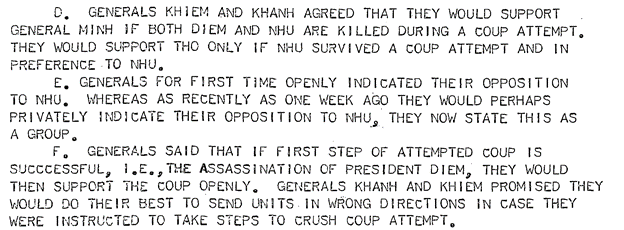

In the early afternoon of the 30th, the Embassy in Saigon sent a telegram to the State Department. The telegram reported a conversation between a CIA CAS [Controlled American Source] officer (likely Conein) and Colonel Pham Ngoc Thao, who had recently attended a dinner with the plotting Generals. Thao explained that Generals Tran Thien Khiem and Nguyen Khanh agreed to support General Duong Van Minh’s coup, provided that Diem and Nhu were killed during the coup attempt. “Generals,” the document continued, “said that if first step of attempted coup is successful, i.e. the assassination of President Diem, they would then support the coup openly” (Document 3). Half an hour later, the Embassy reported with some apprehension that General Khiem, one of the main coup plotters, had been called to the Presidential Palace and had spent several hours there, while at the same time refusing to take U.S. calls. The coup seemed to be in peril.

By the following day, the coup had indeed petered out. The U.S. government had refused to cut U.S. aid as the Generals had requested. General Khiem also claimed that the Generals did not have a favorable balance of forces, an assessment Harkins agreed with. On September 10, during a PFIAB meeting, CIA director McCone expressed relief that the plan had been aborted (Document 4). He denied Vietnamese press allegations that the Agency was behind efforts to remove Diem from power and said the plan to “unload the Nhus” (contained in DepTel 243) was misguided. The decision to send such a telegram was the result of “miscalculation of the Generals’ true capabilities and intentions.” McCone reassured the Agency’s overseers that such a policy was now on the backburner (Document 4).

In Saigon, though, the failure of the August coup became a main element of contention between the CIA, especially Richardson, and Lodge. The former believed that the coup had failed because the Generals did not have the capabilities to carry it out, regardless of the extent of U.S. assurances. In Richardson’s assessment, “there was a clear distinction between our full encouragement and actually being in a position to put together the ingredients for a successful coup” (Document 7). Lodge, though, came to see Richardson and his unwillingness to explicitly support the Generals as the main reason for the August coup failure (Document 7).

The Lodge-Richardson rift intensifies

In mid-September, Lodge started calling for Richardson to be replaced as Chief of Station by General Edward Lansdale. On September 18, the prospect was raised during a meeting between McCone, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, and Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs W. Averell Harriman (Document 5). While no clear policy on how to deal with Diem emerged during the meeting, several concerns were raised regarding the U.S. and especially the CIA’s relationship with Nhu. The CIA had been having weekly meetings with Nhu, and one was upcoming. Since Lodge was opposed, it was agreed to cancel the meeting. U.S. officials continued to disagree on the future of Nhu. On the matter of replacing Richardson, McCone expressed his “unalterable opposition” to sending Lansdale as new Chief of Station (Document 5). McCone repeated his opposition one day later in a strongly worded and personal letter to Lodge. “General Lansdale,” McCone wrote, “would not be acceptable to the organization nor to me personally” (Document 6). The CIA’s director was also very critical of Lodge’s treatment of Richardson. Despite Lodge’s claims that he had no problems with Richardson, intelligence collected by the Agency pointed to Lodge’s efforts to ostracize Richardson. McCone did recognize, though, that Richardson was close to Nhu and—were a coup to go ahead—believed he should probably be replaced (Document 6).

In early October, the CIA’s meetings with the Generals restarted. By now, Conein had become the Agency’s main point of contact with the Generals, and contrary to Richardson, Lodge trusted him to execute his directives. In a meeting on the 2nd between General Minh and Conein, the former asked for a confirmation of U.S. posture towards a coup and assurances that the U.S. would not “thwart” a coup if one were to get underway. Minh stated that the Generals did not require U.S. support and outlined three main options: i) the assassination of Ngo Dinh Nhu and Ngo Dinh Can, keeping Diem in office, ii) the encirclement of Saigon by various military units, or iii) a direct confrontation between the coup plotters and the remaining troops (Document 19). On the 5th, Lodge asked State for confirmation of what Conein should tell the General the next time they met. Lodge agreed that the U.S. should state that they would not thwart a coup, Conein should also offer to review the Generals’ plans, except for the assassination plans (Document 8). On the same day, a telegram to Lodge confirmed U.S. government policy. “No initiative should now be taken” the telegram read, “to give any active covert encouragement to a coup.” U.S. officials should work to identify possible alternative leadership, but this effort had to be “secure and fully deniable,” as well as separated from the normal reporting work.

Two days later, on October 7, the crippling dysfunction and mistrust between Richardson and Lodge became evident during a meeting between McCone, Colby, and Richardson, who had been temporarily recalled to the U.S. (Document 9). Participants criticized the extensive compartmentalization of information and dysfunction in Saigon, with Lodge cutting the CIA country team out of the decision-making process. CIA leadership speculated that Lodge had used press leaks to further his position and undermine Richardson. The distrust between Lodge and the Agency had reached a boiling point. The State Department was also on the case. It wrote Lodge that David Halberstam had a quote from him stating that he would have been happier with a new CIA Station Chief. State asked for the leaks to stop and to work together to “ensure a more accurate reflection of our common commitment to a single governmental policy.”

The controversy surrounding assassination

As detailed above, the assassination of Diem and Nhu had been openly discussed by the Generals with CIA operatives as an essential element to the planned August coup (Document 3). In October, when the assassination (of Nhu and Can) was listed as one of the Generals’ preferred options, a controversy ensued as to what the U.S. government posture should be. With Richardson out, Acting CIA Saigon Chief of Station Dave Smith told Langley that he had discussed the latest Conein-Minh meeting with Lodge and his deputy William C. Trueheart. Smith recommended: “we do not set ourselves irrevocably against assassination plot since the other two alternatives mean either a bloodbath in Saigon or a protracted struggle.” Having received Smith’s cable and perhaps already unwilling to discuss assassination with Lodge, McCone sent a stern reply (written by Colby) to withdraw Smith’s recommendation since the U.S. could “not be in a position of actively condoning such course of action and thereby engaging our responsibility therefore.” A CIA cable from Saigon confirmed that McCone’s directive had been acted upon, and that Lodge shared the DCI’s view (Document 19).

This exchange played a prominent role in the 1970s Congressional Investigations. Members of the Church Committee pointed out that McCone’s directive—written by Colby—conformed with other last-minute telegrams that had been sent to distance the U.S. government from any involvement in assassination. A “CYA” effort in the words of one of the Senators. During Colby’s testimony, a key element of contention became whether Conein, the main contact with the Generals, had been made aware of McCone’s directive regarding assassination. At the hearing, Colby had no specific answer. In a later correspondence between the CIA’s William Elder and William Miller of the Senate Select Committee, the former had to admit that the cable traffic on the matter remained unclear (Document 21).

Towards the November coup

As General Minh’s conspiracy against Diem picked up steam, the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (ExComm) held an off-the-record meeting on October 8 to discuss the South Vietnamese general’s coup proposal. Although McCone and McNamara cautioned against Minh’s plans, President Kennedy liked the proposal, given that it allowed the U.S. to deny its involvement. “I don’t know whether Big Minh’s going to do it or not,” the President explained, “The only thing is, as I understand our position is, well, if he does it, all right, and if you don’t do it, all right. We’re not now—all this—the only difference is, we’re not now going to him and asking him to do it.” The coup was back on.

The CIA’s Conein became the key liaison between the U.S. government and the coup-plotting South Vietnamese Generals. While CIA headquarters expressed some concerns regarding a possible set-up and an effort by General Tran Van Don to—at a minimum—entrap Conein, the meetings continued. In late October, Conein met Don at a dentist's office in Saigon to gauge Washington’s appetite for a coup. Don told Conein that the Generals were not ready to share the coup plan, but that he would receive it two days before the start of the coup. An agreement was reached that, when the coup began, Conein would be invited to the Joint General Staff (JGS) headquarters to secure a direct line of communication between the coup plotters and Ambassador Lodge. Before a redacted section, the last available paragraph reads: “Without being questioned on this point, Gen Don stated that Generals’ Committee had come to the conclusion that the entire Ngo family had to be eliminated from the political scene in Vietnam” A few days after the meeting, Lodge informed the Generals that Conein was authorized to speak for Lodge.

On October 26, less than a week before the coup, several American officials began to get jittery over the conspiracy against Diem. In a message to National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, Lodge stated that he was unconvinced that a coup would take place, as he was not sure General Don had “the iron in his soul” (Document 10). Lodge agreed with Bundy that a failed coup might have had negative repercussions for the U.S. from “persons who wish to damage us.” Yet, if the U.S. government played its cards correctly, Lodge still believed that the U.S. would be able to maintain a “very vigorous denial” that it played any role in the coup.

Three days before the coup, top U.S. officials met at the White House again to discuss the prospects and consequences of overthrowing Diem, but they remained divided (Document 11). The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Maxwell Taylor, stated that regardless of the outcome, a coup would be “disastrous.” Building on Taylor, DCI McCone considered it unwise not to reconsider the U.S. posture since the military adviser to the President (Taylor) was counselling against the overthrow of Diem and Nhu. The President worried about the risk of protracted fighting. RFK doubted whether the U.S. should proceed with a plan that might either fail or create instability even in case of success, especially since a coup might undermine the war effort. Bundy argued that the U.S. could not reverse course and abandon the coup plotters. The record of the meeting makes clear that Washington had widespread knowledge of a growing conspiracy against Diem. The meeting concluded with an agreement to send a cable for a new assessment of the coup’s prospects (Document 11). Four hours later, at another meeting in the White House, Kennedy’s doubts receded as he explained that “the burden of proof should be on the coup promoters to show that they can overthrow the Diem government and not create a situation in which there would be a draw.” The President was clear: he wanted a successful coup.

That same day, from Saigon, Lodge dismissed Washington’s concerns that a coup climate might remove the element of surprise since such a climate had existed for months (Document 12). Lodge also reminded U.S. officials that the Generals had not shown any reliance on U.S. support, nor had they made any specific request for support. If anything, they had demanded “the least possible American involvement.” Lodge—aiming to strengthen confidence in Washington—was also firm in summarizing the U.S. role. “A point which must be completely understood is that we are not engineering this coup.” Under orders not to thwart the coup, the U.S. role had been limited to observing and reporting developments and would rely on Conein’s long-standing relationship with the Generals. Lodge warned that requests for financial and military support had not yet been made but may be forthcoming in the future. Lodge concluded by restating that there was no way of stopping the coup except by betraying it to Diem. He also noted that—since the Generals have moved from a 48 to a 4-hour warning—he would not have time to check with Washington when the coup started. Consequently, Washington would not have the option to influence events on the ground.

Even at this late stage, Colby provided a strong defense of Nhu—who had become the symbol of South Vietnamese instability for those in Washington who favored a coup (Document 13). Nhu, Colby wrote, had been undermined by his reputation as “intriguing, sinister and ruthless” and by his wife’s “harsh and sometimes hysterical utterances.” But Nhu had also been very supportive of U.S.-backed initiatives, such as the Strategic Hamlet program. He had been successful in establishing the Republican Youth, though Colby did acknowledge the movement’s “fascistic” tendencies and the “Potemkin village” character of this (and many other) ventures. Ultimately, Colby wrote, Nhu “represents a strong, reasonably well-oriented, and efficient potential successor to Diem, and the image problems could be addressed through propaganda efforts. “Nhu is a desirable rather than a catastrophic candidate.”

On the same day, on October 30, debates regarding Washington’s options to stop the coup continued, with Lodge stressing that the only option was to betray the coup to Diem (Document 14). While Conein was set to meet the Generals, Lodge also warned against sharing the Generals’ coup plans with the U.S. military since the Generals believed that it was U.S. military personnel in Saigon who had leaked information to Diem. Lodge also made clear that he was prepared to wash his hands of Diem’s fate and would stress to Vietnamese authorities that if President Diem, who is the commander in chief of the armed forces, is unable to stop the coup, then there is nothing that he can do. Finally, Lodge also explained his views on making U.S. funds available for the plotters. They should be made available only if they can be passed discreetly and the U.S. government assesses that the coup will likely succeed.

The coup and Conein

The coup started on November 1 at 1315 Saigon time. Conein was told only two hours in advance. He was asked to join the Generals at the JGS headquarters and to take as much money with him as he could. Conein took 5 million piastres that had been stored in a safe in his house (Document 19). Various versions exist as to what use was made of the money. Having previously warned that the Generals were likely to request money, Lodge was seemingly left out of the decision to pass the money on the day of the coup (Document 19).

During his testimony to the Senate Select Committee, Conein said the money had come from the CIA and for non-controversial purchases like “rice and bread” for troops—“the most important thing”—and to set up medical facilities. Then-DCI Colby told a different version in his testimony, stating that the money had been used to “reward certain opposition units who joined the coup” and that there had been a second transfer of money the following day to provide insurance for the families of those who had died in the coup. He later downplayed the role of the money transfer but admitted that it was likely used to buy the loyalty of additional troops. The issue was so controversial that the part of the CIA Inspector General’s report pertaining to the payoffs was only unredacted only in 2024. Furthermore, Walter Elder, during an investigation in the aftermath of the “Family Jewels” directive, told Colby that the “accounting” for Conein’s money “and its use has never been very frank or complete.”

Document 22 – CIA’s Lucien Conein is awarded the Intelligence Star for his role in the coup against Diem.

In any case, as the coup was underway, Conein and other CIA assets sent regular reports about developments, providing a detailed analysis of the Generals’ thinking and their evolving views on Diem (Document 17). At one point, Conein reported that the Generals were attempting to contact the presidential palace but without success. Their ultimatum was that, if the president were to resign immediately, they would guarantee his safety. If he refused, the palace would be attacked within an hour by air force and armored cars. As Conein wrote, the “ultimatum appears final.” Later in the day, Conein reported that the Generals had “firmly decided there to be no rpt no discussion with the president. He will either say yes or no and that is the end of the conversation.” A later report said they were “preparing heavy air bombardment on palace immediately.”

Diem and his brother Nhu were eventually captured and assassinated in the back of an armored vehicle. Two controversies still surround their final hours. First, at one point, the Generals asked for a plane to take Diem out of the country. Having reported the request to Acting Chief of Station Smith, Conein was told that 24 hours were needed to find a plane that could take Diem to the first country that would offer him asylum. Church Committee investigators identified this as a crucial decision in the Diem coup. Rhett Dawson, Minority Counsel in the Church Committee, wrote to Fritz Schwartz, the Committee’s Chief Counsel, that it was recommended that “the committee examine McGeorge Bundy and others, if necessary, on the delays in air evacuation to asylum.” During congressional testimonies, several U.S. officials, including Conein, Colby, and Bundy, were indeed asked about the delay, but nobody could explain who had made the decision and why. As Dawson wrote, the decision “casts a pall over American involvement in the assassinations of Diem and Nhu.”

A second element remains unclear when trying to ascertain the U.S. role in the coup. The uncertainty is largely due to the different versions of events that have emerged over the years, primarily through one of its main protagonists: Lucien Conein. The problem with Conein, as journalist Stanley Karnow explained, “is that he told you these marvelous stories, but they didn’t always pan out.” When asked by the Church Committee how the assassination happened, Conein testified that he had been caught by surprise. In fact, with the Generals, he had worked on preparing the JGS for the arrival of the media and for a peaceful transfer of power. The Generals, as he told the Committee, decided to kill Diem only at the last minute, angered by Diem’s decision to secretly abandon the palace and defy the delegation sent for his surrender. In later years, Conein repeated the same version of events, with an emphasis on the peaceful transfer of power in various TV interviews.

Even before the Church Committee investigations, though, Conein had provided a different version. During a 1971 NBC News program, Vietnam Hindsight, Part II: The Death of Diem, Conein explained how—when the Generals wavered—he had offered incitement and support. As he recalled, he told the Generals, “Once you are into the attack, you must continue. If you hesitate, you are going to be lost.” More importantly, Conein claimed that he could not explicitly discuss the Generals’ decision on Diem, as he knew they were part of a “blood oath” and he did not want to divulge “privileged information.” However, Conein did agree that the Generals’ decision was not a last-minute one. There had been a vote among the Generals, and they had decided to assassinate Diem (Document 20). In 1981, the Generals’ decision to kill Diem was confirmed by General Tran Van Don. Don admitted that the Generals’ feared a change of heart by the United States. If Diem had been kept prisoner, “perhaps after three months the Americans would have replaced him and the Generals by bringing back the Nhus” (Document 23).

A certain degree of mystery and obfuscation, then, remains regarding Diem’s final hours and Conein’s role in the coup. The 2025 release of Conein’s personnel file seems to confirm that Conein was no mere passive spectator of the coup, as he was awarded the “intelligence star” for his services during those critical months in Vietnam (Document 22). An intelligence star is awarded “for a voluntary act or acts of courage performed under hazardous conditions or for services rendered with distinction under conditions of great risk.” This suggests that the CIA saw Conein as much more than a simple bystander to the evolving coup.

This shows McCone’s views on assassination. During the Congressional investigations of the 1970s, McCone testified that for moral and - as in the case of Diem - strategic reasons he was opposed to and could not discuss assassination. In later years, his assistant William Elder had stated that McCone would ask CIA officials not to inform him of assassination plots. Here, he seems more open to talk about it. Luca Trenta, The President’s Kill List (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2024), p. 99.

The episode has also been covered extensively. Scholarship on Vietnam is, of course, rich and diverse. Works that deal at length with the Diem coup include Howard Jones, Death of a Generation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Fredrik Logevall, Choosing War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); John Prados, Vietnam: the History of an Unwinnable War, 1945-1975 (University Press of Kansas, 2013); Nichter, The Last Brahmin; Lindsey O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018); William J. Rust, Kennedy in Vietnam (New York: Da Capo Press,1985); Ken Hugues “Silence: JFK’s Role in the Overthrow and Assassination of South Vietnamese President Ngô Đình Diệm,” Miller Center’s Presidential Recordings Digital Edition, and Trenta, The President’s Kill List. The episode is also covered in Rust’s biography of Conein in Studies in Intelligence, the CIA in-house journal. See William Rust, “CIA Operations Officer Lucien Conein: A Study in Contrasts and Controversy,” Studies in Intelligence Vol. 63, No. 4 (2019), 43-58.

For his classic book on the Vietnam War, see George McTurman Kahin, Intervention: How America Became Involved in Vietnam (Alfred A. Knopf, 1986).

For instance, Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) was adamant that his brother did not approve a coup against Diem. RFK was not present during most of the key meetings where the President argued in favor of a coup. See Luke Nichter, The Last Brahmin: Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. and the Making of the Cold War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020), pg. 209.

William Colby testimony, U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, June 20, 1975. JFK Assassination Records, 2017 release, 157-10014-10019, pg. 30.

Nichter’s excellent biography of Lodge presents a different interpretation of the ambassador’s position towards the coup as not fully supportive. We see Lodge as very much in favor of a coup, with Colby and McCone as the key actors opposed to the coup. See Nichter, The Last Brahmin, pg. 217.

Telegram, CIA to White House situation room, 29 August 1963, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library (JFKL), National Security File (NSF), Vietnam General, Folder “August 1963 24-31, CIA cables, JFKNSF-198-009.”

Message From the President to the Ambassador in Vietnam (Lodge), Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Document 18.

Lodge telegram to Kennedy, August 30, 1963, GRFL Saigon Embassy Files, Box 8, Folder "Henry Cabot Lodge, Including Diem Coup, 1963-65 (2).”

Telegram, Saigon to Secretary of State, 30 August 1963, JFKL, NSF, Vietnam General, Folder, “August 1963 24-31, CIA cables JFKNSF-198-009.”

Trenta, The President’s Kill List, 139.

Telegram, CIA to State, 31st August, JFKL, NSF, Vietnam General, Folder, “August 1963 24-31, CIA cables JFKNSF-198-009.”

It is not clear why McCone was so opposed to Lansdale as Saigon Chief of Station. Lansdale's poor performance leading Operation Mongoose against Cuba burned many bridges at Langley where he gained a a reputation as a “wild man” within the CIA. See Max Boot, The Road Not Taken: Edward Lansdale and the American Tragedy in Vietnam (Liveright, 2018), pg. 114.

Richardson would be replaced by his deputy David Smith who would become Acting Saigon Chief of Station.

Nichter, The Last Brahmin, pg. 220.

Telegram to Lodge, via CAS Channel, 5 October 1963, JFKL, NSF Vietnam Top Secret cables, Folder, “Tab C, October 1963 JFKNSF-204-012.”

Telegram, State to American Embassy Saigon, 4 October, 1963, JFKL, NSF, Vietnam Top Secret Cables, Folder “Tabs A-B, October 1963 JFKNSF-204-011.”

The same dynamic also emerges in other episodes of US government’s involvement in assassination, such as the case of Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic. It is also discussed explicitly in the 1970s Congressional inquiries. Trenta, The President’s Kill List, pp. 124-125.

William Colby testimony, pg. 53-54.

Telegram, McCone to Saigon, 24 October 1963, JFKL, NSF, Vietnam Top Secret cables, Folder “Tab C, October 1963 JFKNSF-204-012.”

CIA Saigon to Washington, 25 October 1963, GRFL Saigon Embassy Files, Box 8, Folder “Henry Cabot Lodge, Including Diem Coup, 1963-65 (3).”

Telegram, Lodge to Secretary of State et al., October 28, 1963, GRFL Saigon Embassy Files, Box 8, Folder “Henry Cabot Lodge, Including Diem Coup, 1963-65 (3).”

Memorandum of a Conference with President Kennedy, October 29, 1963. FRUS, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, Document 235. See also Hugues, “Silence.”

This document is undated and it is possible that it was written prior to late October. However, according to the CIA’s FOIA webpage, the date of the document is October 30, 1963.

Lucien Conein testimony, U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, June 20, 1975. JFK Assassination Records, 2017 release, 157-10014-10094.

William Colby Testimony, U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, June 4, 1975. JFK Assassination Records, 2017 release, 157-10002-10172, pgs. 124-125.

Colby Testimony, June 20, 1975, pg. 46.

William Elder, Memorandum for William Colby, “Special Activities,” June 1, 1973.

Rhett Dawson to Fritz Schwarz, “Diem Assasination,” 7 July 1975. JFKAR 2025 Release, No. 157-10014-10152.

Rust, “CIA Operations Officer Lucien Conein,” pg. 44.

Conein testimony June 20, 1975, pg. 55.

Lucien Conein, Interview, Vietnam: A Television History, 7 May1981.

In his memoirs, though, Don had provided a different narrative, he had denied that there had been a vote, stating instead that no vote was taken, and the lack of a clear decision was responsible for Diem’s and Nhu’s deaths. Tran Van Don, Our Endless War (San Rafael: Presidio Press, 1978), pp. 110-111.

CIA Medals: Intelligence Star.

Founded in 1985 by journalists and scholars to check rising government secrecy, the National Security Archive combines a unique range of functions: investigative journalism center, research institute on international affairs, library and archive of declassified U.S. documents ("the world's largest nongovernmental collection" according to the Los Angeles Times), leading non-profit user of the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, public interest law firm defending and expanding public access to government information, global advocate of open government, and indexer and publisher of former secrets.

Related link: New Light in a Dark Corner: Evidence on the Diem Coup in South Vietnam,

Spread the word