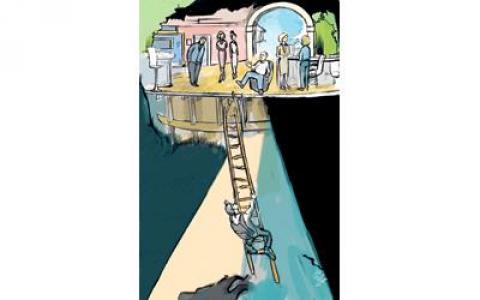

Public discussion about New York State’s responsibility to provide financial support to the City University of New York (CUNY), the nation’s third largest public university system, has been much in the news lately, thanks in large part to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s surprise announcement in January that he wanted to offload $485 million of CUNY’s operating costs from the state budget onto the city. Cuomo’s dramatic budget demand raised fundamental questions about exactly what is the ongoing responsibility of state government to provide budgetary support to public higher education entities within its jurisdiction. To fully understand and come to terms with this key political and fiscal question it is instructive to look back to see how taxpayer-supported public higher education emerged and evolved across the country.

State and federal support for public higher education has a long history, dating back in some states (e.g., Georgia and Virginia) to the decades before and immediately after the American Revolution. CUNY’s own history with its municipal colleges begins in 1847 with the founding of the Free Academy (which would later become City College), followed in 1870 by the opening of Hunter College; both were taxpayer-supported, tuition-free (at least for full-time undergraduates) public entities. Most state-funded public higher education systems, many of them initially created using funds derived from federal land grants to the states, remained fairly small in the decades before World War II in terms of the numbers of students served (New York State, unlike almost all other states, had in fact not even bothered to create a state public university system before the war). World War II changed all of that. The federal government and a number of state governments (including New York’s) decided that they needed to quickly expand state-based public higher education in the postwar era. Driven largely by concerns about potential economic and political unrest — especially given the 16 million returning GIs who would be demanding jobs, education and decent housing — federal and state policymakers determined that higher education opportunities needed to be made more broadly available as a public good, underwritten almost entirely by taxes. One key outcome of this determination, which cut across party and ideological lines, was passage of the 1944 GI Bill. The bill provided tuition and housing support grants from the federal government to almost eight million demobilized soldiers and sailors who poured into public and private colleges, universities and training centers all over the country after 1945.

State legislators across the country, prodded by politically ambitious governors, had begun developing long-range plans as early as 1943 and committed significant levels of public funding to expand their state-level public higher education institutions to meet the anticipated “tidal wave of returning veterans.” Many states focused increased public funding in the postwar years on building community colleges, perhaps the most important expansion of public higher education in the 20th century.

The ideology that helped justify this dramatic expansion of public higher education in the postwar era included an uneasy mix of politically pragmatic (sometimes opportunistic) and visionary, even progressive beliefs. A dominant ideological orientation was utilitarian, articulating the need to prepare a new and rapidly growing generation for the technical and service jobs essential to the transformation and expansion of American capitalism in the postwar era. A second rationale was the need to “do right” by the millions of servicemen (and a far smaller number of women) by giving them access to publicly funded higher education and job training. A third ideological justification for public university expansion focused on enduring democratic ideals and values that had come to the fore in the war against Nazism and fascism. All three rationales — offered by national and state-level political and business leaders, university officials, trade union leaders and pundits — also underscored the need to create an informed democratic citizenry to face the challenges of the postwar era.

New York State had lagged badly behind public higher education pioneers like California (which already had a robust, three-tier, tuition-free public higher education system by 1945) and even New York City, whose municipal higher education system already numbered four senior colleges by the outbreak of the war. New York State finally agreed to create the State University of New York (SUNY) in 1948, though it did little to expand that system over the next ten years. All of that changed with Nelson Rockefeller’s election as governor in 1958. Rockefeller, who was keenly aware of the dramatic expansion of state universities all over the country (especially California’s), launched a massive expansion of New York State’s public university system. New York (State and City) and California entered a kind of planning race to design and rationalize their public university systems after 1958, anticipating the first wave of baby boomers who would be entering state colleges and universities beginning in the early 1960s. Each state (and the city) developed a “master plan” for such public higher education expansion, mixing substantial state investment of capital funds to build many new campuses, free or extremely low-cost tuition paid by state residents who would be attending those campuses, and dramatic growth in the size and function of the teaching and research faculty. This state-level commitment (and, in the unique case of New York State, New York City’s as well) was predicated on a fundamental belief in state and city universities as a public good, essentially tuition free and supported by state and city tax dollars. That state and city commitment to higher education as a public good would be expanded dramatically after the mid-1960s with large infusions of federal support in the form of heavily subsidized student loans.

The decade of the 1960s witnessed the single largest expansion of public higher education in U.S. history, with expenditures more than tripling. College enrollments more than doubled to 8.6 million students (of which two in five were women and many of whom were children of poor and working class parents who would otherwise never would have been able to attend college without free or very low tuition); instructional staff also doubled in the decade to almost 600,000. Millions of baby boomers (including this author) were the greatest beneficiaries of this public investment in free public higher education. New York’s and California’s public higher education systems and the students who flooded into them especially benefited from this massive expansion, resulting in the three largest public university systems (SUNY, California State University and CUNY) in the country by the 1970s.

This “golden age” of public higher education would not last indefinitely, however. What followed in the last quarter of the 20th century was a fundamental neoliberal reshaping of public higher education. The ideology and practice of neoliberalism, resulting in rising inequality and the imposition of austerity policies, brings us to the national debate about whether it is appropriate for public funds to underwrite the costs of public higher education or whether higher education is essentially to be seen as a private good and an individual (or familial) responsibility. The legions of young people flocking to support Bernie Sanders in the Democratic Party primaries are in large part motivated by his arguments in support of free public higher education, harkening back to the postwar era of the GI Bill and the rapid growth of state university systems like those in New York and California. It is disheartening, given the fractious nature of our politics, that many of my fellow baby boomers seem far too quick to dismiss this embrace of free public higher education as an unrealistic pursuit of “free stuff.” As we consider the merits of this crucial question, it is important to remember that an entire generation once enjoyed the fruits of a broad political and ideological consensus that state-supported higher education was a public good very much worth embracing and fighting for. How can we deny the same opportunity to the youth of today?

Stephen Brier is a historian and a professor of urban education at the CUNY Graduate Center. He is co-author, with Michael Fabricant, of Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education (forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press in fall 2016), from which this article is drawn.

The Indypendent is a monthly New York City-based newspaper and website. Subscribe to our print edition here. You can make a donation or become a monthly sustainer here.

Spread the word