The reporter from the Washington Post didn’t ask Donald Trump about nuclear weapons, but he wanted to talk about them anyway. “Some people have an ability to negotiate,” Trump said, of facing the Soviet Union. “You either have it or you don’t.”

He wasn’t daunted by the complexity of the topic: “It would take an hour and a half to learn everything there is to learn about missiles,” he said.

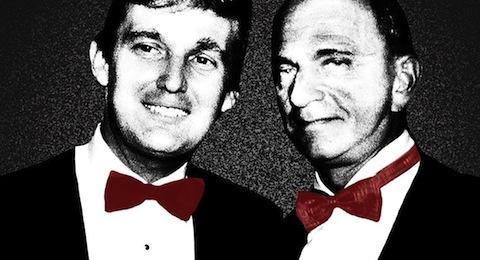

It was the fall of 1984, Trump Tower was new, and this was unusual territory for the 38-year-old real estate developer. He was three years away from his first semi-serious dalliance with presidential politics, more than 30 years before the beginning of his current campaign—but he had gotten the idea to bring this up, he said, from his attorney, his good friend and his closest adviser, Roy Cohn.

That Roy Cohn.

Roy Cohn, the lurking legal hit man for red-baiting Sen. Joe McCarthy, whose reign of televised intimidation in the 1950s has become synonymous with demagoguery, fear-mongering and character assassination. In the formative years of Donald Trump’s career, when he went from a rich kid working for his real estate-developing father to a top-line dealmaker in his own right, Cohn was one of the most powerful influences and helpful contacts in Trump’s life.

Over a 13-year-period, ending shortly before Cohn’s death in 1986, Cohn brought his say-anything, win-at-all-costs style to all of Trump’s most notable legal and business deals. Interviews with people who knew both men at the time say the relationship ran deeper than that—that Cohn’s philosophy shaped the real estate mogul’s worldview and the belligerent public persona visible in Trump’s presidential campaign.

“Something Cohn had, Donald liked,” Susan Bell, Cohn’s longtime secretary, said this week when I asked her about the relationship between her old boss and Trump.

By the 1970s, when Trump was looking to establish his reputation in Manhattan, the elder Cohn had long before remade himself as the ultimate New York power lawyer, whose clientele included politicians, financiers and mob bosses. Cohn engineered the combative response to the Department of Justice’s suit alleging racial discrimination at the Trumps’ many rental properties in Brooklyn and Queens. He brokered the gargantuan tax abatements and the mob-tied concrete work that made the Grand Hyatt hotel and Trump Tower projects. He wrote the cold-hearted prenuptial agreement before the first of his three marriages and filed the headline-generating antitrust suit against the National Football League. To all of these deals, Cohn brought his political connections, his public posturing and a simple credo: Always attack, never apologize.

“Cohn just pushed through things—if he wanted something, he got it. I think Donald had a lot of that in him, but he picked up a lot of that from Cohn,” Bell said.

“Roy was a powerful force, recognized as a person with deep and varied contacts, politically as well as legally,” Michael Rosen, who worked as an attorney in Cohn’s firm for 17 years, told me. “The movers and shakers of New York, he was very tight with these people—they admired him, they sought his advice. His persona, going back to McCarthy … and his battles with the government certainly attracted clients.”

It was a long, formidable list that included the executives of media empires, the Archbishop of New York and mafia kingpin Fat Tony Salerno, and there, too, near the top, was budding, grasping Donald John Trump.

“He considered Cohn a mentor,” Mike Gentile, the lead prosecutor who got Cohn disbarred for fraud and deceit not long before he died, said in a recent interview.

People who knew Cohn and know Trump—people who have watched and studied both men—say they see in Trump today unmistakable signs of the enduring influence of Cohn. The frank belligerence. The undisguised disregard for niceties and convention. The media manipulation clotted with an abiding belief in the potent currency of celebrity.

Trump did not respond to a request from Politico to talk about Cohn. In the past, though, when he has talked about Cohn, Trump has been clear about why he collaborated with him, and admired him.

“If you need someone to get vicious toward an opponent, you get Roy,” he told Newsweek in 1979.

A year later, pressed by a reporter from New York magazine to justify his association with Cohn, he was characteristically blunt: “All I can tell you is he’s been vicious to others in his protection of me.”

He elaborated in an interview in 2005. “Roy was brutal, but he was a very loyal guy,” Trump told author Tim O’Brien. “He brutalized for you.”

Trump, in the end, turned some of that cold calculation on his teacher, severing his professional ties to Cohn when he learned his lawyer was dying of AIDS.

***

Cohn and Trump, according to Trump, met in 1973 at Le Club, a members-only East Side hangout for social-scene somebodies and those who weren’t but wanted to be.

By then Cohn had been in the public eye for 20 years. As chief counsel to McCarthy, he led secretive investigations of people inside and outside the federal government whom he and McCarthy suspected of Communist sympathies, homosexuality or espionage. Over a period of several years, McCarthy’s crusade destroyed dozens of careers before a final 36-day, televised hearing brought his and Cohn’s often unsubstantiated allegations into the open, leading to McCarthy’s censure in the Senate. Cohn, disgraced by association, retreated to his native New York.

There, through the ‘60s and into the ‘70s, Cohn embraced an unabashedly conspicuous lifestyle. He had a Rolls-Royce with his initials on a vanity plate and a yacht called Defiance. He was a singular nexus of New York power, trafficking in influence and reveling in gossip. He hung on the walls of the East 68th Street townhouse, that doubled as the office of his law firm, pictures of himself with politicians, entertainers and other bold-face names. He was a tangle of contradictions, a Jewish anti-Semite and a homosexual homophobe, vehemently closeted but insatiably promiscuous. In 1964, ’69 and ’71, he had been tried and acquitted of federal charges of conspiracy, bribery and fraud, giving him—at least in the eyes of a certain sort—an aura of battle-tested toughness, the perception of invincibility. “If you can get Machiavelli as a lawyer,” he would write in The Autobiography of Roy Cohn, “you’re certainly no fool of a client.”

Trump was 27. He had just moved to Manhattan but was still driving back to his father’s company offices in Brooklyn for work. He hadn’t bought anything. He hadn’t built anything. But he had badgered the owners of Le Club to let him join, precisely to get to know older, connected, power-wielding men like Cohn. He knew who he was. And now he wanted to talk.

He and his father had just been slapped with Department of Justice charges that they weren’t renting to blacks because of racial discrimination. Attorneys had urged them to settle. Trump didn’t want to do that. He quizzed Cohn at Le Club. What should they do?

He became Donald’s mentor, his constant adviser on every significant aspect of his business and personal life.”

“Tell them to go to hell,” Cohn told Trump, according to Trump’s account in his book The Art of the Deal, “and fight the thing in court.”

That December, representing the Trumps in United States v. Fred C. Trump, Donald Trump and Trump Management, Inc., Cohn filed a $100-million countersuit against the federal government, deriding the charges as “irresponsible” and “baseless.”

The judge dismissed it quickly as “wasting time and paper.”

The back-and-forth launched more than a year and a half of bluster and stalling and bullying—and ultimately settling. But in affidavits, motions and hearings in court, Cohn accused the DOJ and the assisting FBI of “Gestapo-like tactics.” He labeled their investigators “undercover agents” and “storm troopers.” Cohn called the head of DOJ down in Washington and attempted to get him to censure one of the lead staffers.

The judge called all of it “totally unfounded.”

They hashed out the details of a consent decree. The Trumps were going to have to rent to more blacks and other minorities and they were going to have to put ads in newspapers—including those targeted specifically to minority communities—saying they were an “equal housing opportunity” company. Trump and his father, emboldened by Cohn, bristled at the implication of wrongdoing—even, too, at the cost of the ads.

“It is really onerous,” Trump complained.

At one point, flouting the formality of the court, Trump addressed one of the opposing attorneys by her first name: “Will you pay for the expense, Donna?”

Trump and Cohn seemed most concerned with managing the media. They squabbled with the government attorneys over the press release about the disposition. First they wanted no release. Impossible, said the government. Then they wanted “a joint release.” A what? A public agency, it was explained to them, had a public information office, on account of the public’s right to know.

Cohn didn’t want to hear it.

“They will say what they want,” he told the judge, and everybody else in the courtroom, “and we will say what we want.”

The government called the consent decree “one of the most far reaching ever negotiated.”

Cohn and Trump? They called it a victory.

Case 73 C 1529 was over. The relationship between Cohn and Trump had just begun.

“Though Cohn had ostensibly been retained by Donald to handle a single piece of litigation,” Wayne Barrett, an investigative journalist for New York’s Village Voice, would write in his 1992 book about Trump, “he began in the mid-‘70s to assume a role in Donald’s life far transcending that of a lawyer. He became Donald’s mentor, his constant adviser on every significant aspect of his business and personal life.”

The wedding was at Manhattan’s Marble Collegiate Church, presided over by Norman Vincent Peale, the eminent hawker of the power of positive thinking. The guests included the mayor, other city politicians, comedian Joey Adams and his wife—the New York Post gossip columnist Cindy Adams—and Cohn, of course, who served as emcee of sorts at the reception.

By this time, Trump was in the thick of trying to make the first major move of his business career—the ambitious refurbishment of the crumbling Commodore hotel in the then-down-and-out area around Grand Central station. Trump wanted to turn it into a lavish Grand Hyatt, and did. The only way he was able to do it, though, was an unprecedented 40-year, $400-million tax abatement from the city. And the only way he got it was Cohn. Cohn had been tagged as “a legal executioner” in a 1978 piece in Esquire. The meticulously reported and roundly unflattering profile prompted Cohn to call the writer, Ken Auletta, who was amazed to hear Cohn ask if he could buy 100 copies. “One of the most reptilian characters I’ve ever met,” Auletta told me. For the Hyatt deal, Cohn called upon his deep relationships with the mayor, Abe Beame, and one city hall staffer, Stanley Friedman, who practically singlehandedly pushed through the last approvals and then promptly went to work for Cohn’s law firm.

If the race case was Trump’s introduction to Cohn, and the prenup a blending of the personal and professional, the Grand Hyatt was a master class.

“Cohn’s exploitation of Friedman to secure the Commodore booty was an unforgettable lesson for Donald,” Barrett later wrote, “exposing him to the full reach of his mentor’s influence and introducing him to the netherworld of sordid quid pro quos that Cohn ruled. This almost ritualistic initiation not only inducted Donald into the circle of sleaze that engulfed Cohn, the bountiful success of it transferred the predatory values and habits Cohn embodied to his yearning understudy.”

Cohn, the New York Daily News said in 1979, was “the city’s preeminent manipulator,” a “one-man network of contacts that have reached into City Hall, the mob, the press, the Archdiocese, the disco-jet set, the courts and the backrooms of the Bronx and Brooklyn where judges are made and political contributions arranged.”

In the New York Times in 1980, Cohn called himself “not only Donald’s lawyer, but also one of his close friends.”

They talked, according to Vanity Fair, “15 to 20 times a day.”

Cohn’s vanity plate on his Rolls: RMC. Trump’s vanity plate on his Cadillac limo: DJT.

“The Bible says that the meek shall inherit the earth,” Cohn wrote, in 1981, in his new book, How to Stand Up For Your Rights & Win. “But in my experience the only earth the meek inherit is that in which they are eventually buried.”

On occasion, when negotiations faltered, according to the Times, Trump would pull out a picture of Cohn. “Would you rather deal with him?”

Hanging on the wall in Cohn’s office was a photo of Trump, according to Gary Belis, the former director of public relations for Fortune magazine, and Trump had signed it. “To Roy,” he had written. “My greatest friend. Donald.”

On September 5, 1980, according to Jerome Tuccille’s 1985 biography of Trump, Trump was the star of—finally—the grand opening of the Grand Hyatt. The governor, the mayor, the former mayor—they all were there, and so, obviously, was Cohn.

Cohn helped Trump get a $20-million tax abatement for Trump Tower, which was built almost entirely of concrete, at a time when the New York concrete industry was controlled by various mob associates, who played nice with Trump thanks to his go-to go-between. “I knew Trump quite well,” John Cody, a key concrete boss, said in Barrett’s book. “Donald liked to deal with me through Roy Cohn.”

Cohn represented the United States Football League when Trump owned the second-tier league’s New Jersey Generals and filed an ill-advised antitrust suit against the National Football League, alleging that the NFL was an unfair monopoly. “I talked to Roy about this USFL suit; he’s represented me for a lot of years,” Trump told reporters. Cohn invoked the same sort of conspiratorial language he had used in the ‘50s, representing McCarthy in Washington, and in the ‘70s, representing Trump in New York. The NFL, he said, had instituted a “secret committee” to squash the USFL. At the press conference announcing the suit, no other USFL official stood by Trump. Only Cohn.

Cohn by this time had been hit with charges of “fraud, deceit and misrepresentation”—for lying on a bar application, for taking a client’s money, for altering the will of an incapacitated man, among other things—that would lead to his disbarment in July 1986. He habitually sneered at prosecutors, and now, unrepentant, he denigrated them as “deadbeats,” “yo-yos” and “nobodies.” He had been diagnosed as HIV-positive the same month as the initiation of the USFL suit, but told nobody—certainly not Trump, who had testified on Cohn’s behalf in the disbarment proceedings, one of 37 character witnesses, praising him for his loyalty.

Trump, though, found out about Cohn’s AIDS, because people knew, and people talked, and he started pulling legal business from Cohn and transferring it to other attorneys—something he did in the USFL matter in March 1985. Cohn couldn’t believe it. After all he had done for Trump? “Donald pisses ice water,” he said, according to Barrett’s book.

“Donald found out about it and just dropped him like a hot potato,” Bell, Cohn’s secretary, told me. “It was like night and day.”

Cohn died August 2, 1986, dishonest to the end, insisting he had liver cancer. The funeral was a who’s who. Mayors and governors and senators and city commissioners. Barbara Walters. Rupert Murdoch. Estee Lauder. It ended with them singing what Cohn had said was his favorite song. “God Bless America.” Trump stood in the back. He hadn’t been asked to talk.

***

Not quite a year and a half later, on a Saturday night in December of 1987, Trump threw himself a party. The reason was the release of The Art of the Deal. He billed it as “The Party of the Year.” Replete with a red carpet and waiters in white jackets, the atrium of Trump Tower was stocked unavoidably with a glittering array of Cohn’s A-list connections—Walters, Norman Mailer, former governor Hugh Carey, Manhattan borough president Andrew Stein, gossip columnist Liz Smith. Next to Trump: his wife, and also Si Newhouse—the owner of Random House, the publisher of Trump’s book, but a longtime friend, too, of the fixer behind so much of Trump’s best, most effective work.

“I don’t kid myself about Roy. He was no Boy Scout,” Trump had written in the book that became a surprising runaway bestseller. “He once told me that he’d spent more than two thirds of his adult life under indictment on one charge or another. That amazed me. I said to him, ‘Roy, just tell me one thing. Did you really do all that stuff? He looked at me and smiled. ‘What the hell do you think?’ he said. I never really knew.”

Trump now was saying he was “not embarrassed” to say he was friends with Cohn.

I knew Roy,” he said. “I can hear his voice.”

In 1992, though, responding to questions about his relationship with Cohn, and Cohn’s relationship with the mob, from New Jersey’s Division of Gaming Enforcement and Casino Control Commission, Trump distanced himself from a man he once had called “a genius,” his attorney whose name, face and reputation he would brandish as a weapon. But Cohn, he said, was just “one of many lawyers” he had hired. The agencies’ report noted: Trump “disputes that Cohn was an aide or confidant and indicates that he did not require Cohn to act as an intermediary.” According to Trump, the report continued, “he was and is familiar with most of the prominent officials in New York and did not, and does not need an intermediary on his behalf.”

And then, five years later—in an interview with O’Brien, the author of TrumpNation—Trump said Cohn had done for him “a very effective job.”

Even such opportunistic contortions as these—dropping him, claiming him, shunning him, praising him—are themselves residue of Cohn’s influence. Say anything. Win at all costs.

Trump’s status now as the Republican frontrunner in a sense can be traced back to 1984 and the 26th floor of Trump Tower, when he took Cohn’s advice and cashed in some of his celebrity to talk about foreign policy, initiating an extended series of flirtations with the presidency—in 1988, when really he was promoting a book; in 2000, when he dallied with the Reform Party; and in the Obama years, when he championed the conspiracy theory that questioned the president’s birthplace—until last summer’s announcement that he wanted to make America great again by making Mexico pay for a wall.

“The gestures Donald makes, the way he states things, the way he pushes out his lips—all that is his,” said Bell, Cohn's secretary. “But I think some of the ‘Let’s go get ‘em!’ came from Cohn.”

“There’s a certain zig-zaggy crazy irrationality about Trump you might say is somewhat parallel to Roy,” Nick von Hoffman, the author of Citizen Cohn, told me from his home in Maine.

“Yes, he learned from Roy Cohn; yes, he looked up to Roy Cohn,” said Auletta, who wrote the 1978 profile in Esquire. “There’s no question that there are characteristics Roy Cohn had that Donald has.”

His tough-talking, anti-establishment campaign is a cynical, Cohn-like mix of patriotism and paranoia. It is the product of a savvy, studied read on the wants and needs of a competitive press. It runs on personal insults and political kills.

“Anybody who hits me, we’re going to hit them 10 times harder,” Trump vowed last year. It’s one promise he kept.

“Low-energy Jeb.” “Little Marco.” “Lyin’ Ted.”

Cohn, dead 30 years this summer, no doubt would recognize the techniques his mentee has honed.

“It’s not only the ways in which Roy Cohn shaped his empire—it’s the way he shaped his personality,” said Barrett, the dogged reporter who first outlined the importance of this relationship. Now he watches Trump on the TV in his townhouse in Brooklyn.

“I knew Roy,” he said. “I can hear his voice.”

Spread the word