On June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court struck down the heart of the Voting Rights Act, ruling that states with the longest histories of voting discrimination no longer had to approve their voting changes with the federal government. A month after that decision, North Carolina—where 40 counties were previously subject to that requirement—passed the country’s most sweeping voting restrictions.

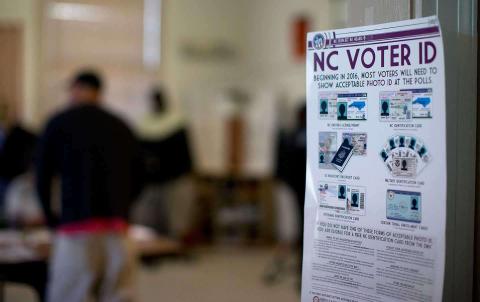

The state required strict voter ID to cast a ballot, cut a week of early voting and eliminated same-day voter registration, out of precinct voting and pre-registration for 16- and 17-year-olds. Today the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit invalidated these restrictions, which it said “targeted African Americans with almost surgical precision” in violation of the Voting Rights Act and the 14th Amendment. It reversed a 485-page decision by the district court upholding the law.

This is a huge victory for voting rights—the most significant in the country since the Shelby County v. Holder decision—that will make it easier for hundreds of thousands of voters to cast a ballot this November. It comes just a week before the 51st anniversary of the VRA on August 6, and is especially welcome because there were widespread voting problems during North Carolina’s presidential primary in March that offered a disturbing preview of what to expect in the general election—students waited in three-hour lines, foreign-born US citizens were asked to spell their names to poll workers for no reason in an apparent literacy test, and elderly voters born during Jim Crow were turned away from the polls.

Most notably, the Fourth Circuit court found that GOP legislators restricted the right to vote to intentionally target African-American voters. North Carolina passed a series of reforms beginning in 2000 that benefited all voters, particularly black voters, wrote Judge Diana Motz, a Clinton appointee, in a unanimous opinion.

During the period in which North Carolina jurisdictions were covered by Section 5, African American electoral participation dramatically improved. In particular, between 2000 and 2012, when the law provided for the voting mechanisms at issue here and did not require photo ID, African American voter registration swelled by 51.1%.

African American turnout similarly surged, from 41.9% in 2000 to 71.5% in 2008 and 68.5% in 2012.

Then, after these gains occurred and the Supreme Court gutted the VRA, North Carolina Republicans swiftly curtailed or eliminated every voting reform in the state that expanded political participation.

After years of preclearance and expansion of voting access, by 2013 African American registration and turnout rates had finally reached near-parity with white registration and turnout rates. African Americans were poised to act as a major electoral force. But, on the day after the Supreme Court issued Shelby County v. Holder, 133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013), eliminating preclearance obligations, a leader of the party that newly dominated the legislature (and the party that rarely enjoyed African American support) announced an intention to enact what he characterized as an “omnibus” election law. Before enacting that law, the legislature requested data on the use, by race, of a number of voting practices. Upon receipt of the race data, the General Assembly enacted legislation that restricted voting and registration in five different ways, all of which disproportionately affected African Americans.

In response to claims that intentional racial discrimination animated its action, the State offered only meager justifications. Although the new provisions target African Americans with almost surgical precision, they constitute inapt remedies for the problems assertedly justifying them and, in fact, impose cures for problems that did not exist. Thus the asserted justifications cannot and do not conceal the State’s true motivation.

Faced with this record, we can only conclude that the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the challenged provisions of the law with discriminatory intent.

The court’s opinion is a striking rebuke to Chief Justice John Roberts’s ruling that voting discrimination is largely a thing of the past. “It calls Shelby into question,” says Allison Riggs of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, which argued the case along with the Justice Department, Advancement Project, and ACLU. “Justice Roberts says we live in post-racial society, and this is strong evidence we don’t.”

North Carolina has been no stranger to voting discrimination in recent decades—the court found that the Department of Justice objected fifty times to discriminatory voting changes from 1980 to 2013 and private lawyers won 55 successful cases under the VRA.

The intentional discrimination undertaken by the North Carolina legislature could not be dismissed as mere partisanship.

We recognize that elections have consequences, but winning an election does not empower anyone in any party to engage in purposeful racial discrimination. When a legislature dominated by one party has dismantled barriers to African American access to the franchise, even if done to gain votes, “politics as usual” does not allow a legislature dominated by the other party to re-erect those barriers.

When it came to early voting, North Carolina admitted that it eliminated voting on a Sunday before the election because “counties with Sunday voting in 2014 were disproportionately black” and “disproportionately Democratic.” The court called this “as close to a smoking gun as we are likely to see in modern times, the State’s very justification for a challenged statute hinges explicitly on race — specifically its concern that African Americans, who had overwhelmingly voted for Democrats, had too much access to the franchise.”

The court said the state could only restrict voting rights if it had a good reason for doing so—which it did not. It questioned, for example, whether the voter-ID law was really meant to stop voter fraud, since the measure required ID for in-person voting, used more by Democrats and African Americans, but not for absentee ballots, used more by Republicans and whites—even though that’s where fraud is far more common

The photo ID requirement, which applies only to in-person voting and not to absentee voting, is too narrow to combat fraud. On the one hand, the State has failed to identify even a single individual who has ever been charged with committing in-person voter fraud in North Carolina. On the other, the General Assembly did have evidence of alleged cases of mail- in absentee voter fraud. Notably, the legislature also had evidence that absentee voting was not disproportionately used by African Americans; indeed, whites disproportionately used absentee voting. The General Assembly then exempted absentee voting from the photo ID requirement.

North Carolina tried to soften its voter-ID law before the federal trial, allowing those with strict government-issued ID to cast a ballot if they listed a “reasonable exception,” but the court said the law still discriminated against voters. “Nothing in this record shows that the reasonable impediment exception ensures that the photo ID law no longer imposes any lingering burden on African American voters.”

This is significant, because courts have recently ruled that voters in Wisconsin and Texas should be offered similar reasonable exceptions, which the court in North Carolina suggested will only partially ameliorate the burdens of such laws.

In 2012, 10 major voting restrictions were blocked in court before the election and a similar trend may be occurring in 2016. As Rick Hasen noted, “This decision is the third voting rights win in two weeks.” There are still too many barriers in too many states, but it’s a good sign that courts are starting to call out these laws for what they really are.

Copyright © 2016 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. Distributed by Agence Global. rights@agenceglobal.com

Spread the word