TORONTO, Canada – As reports came in that members of Turkey’s military were staging a coup on 15 July, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan quickly denounced the person he believed was behind the insurrection.

The Turkish president repeatedly said the coup-plotters were being directed “from Pennsylvania,” a reference to the Justice and Development Party (AKP) leader’s rival, US-based Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen.

In the days since the failed coup attempt, Ankara has formally called on the US government to extradite Gulen, who has been living in self-imposed exile in the state of Pennsylvania since 1999.

“Once they hand over that head terrorist in Pennsylvania to us, everything will be clear,” Erdogan told a crowd in Istanbul last Saturday.

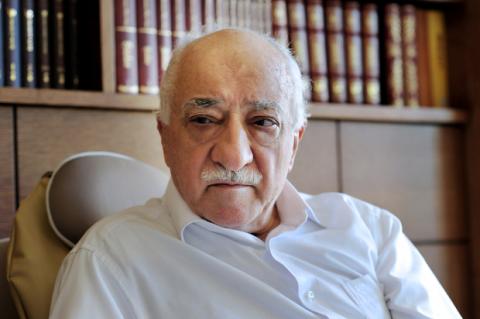

Gulen, meanwhile, has denied any involvement in the attempted coup, accusing Erdogan of using it as a pretext to attack him and his supporters. “It is ridiculous, irresponsible and false to suggest I had anything to do with the horrific failed coup,” the cleric said in a statement on Tuesday.

“I urge the US government to reject any effort to abuse the extradition process to carry out political vendettas.”

But major questions linger about Gulen’s involvement, and the role members of the wider Gulenist movement, also known as the Hizmet (Service) movement, in recent events.

Who is Gulen?

Fethullah Gulen was born in 1941 near Erzurum, in northeastern Turkey, and first came to prominence as a Muslim preacher and intellectual in the 1970s, advocating for interfaith dialogue, modern education, and faith-based activism.

“The Gulen movement differentiates itself from other Islamic movements by stressing the importance of ethics in education, media, business, and public life,” wrote Gurkan Celik, author of “The Gulen Movement: Building Social Cohesion through Dialogue and Education,” which presents a very positive review of Gulen’s ideology and activities.

The Gulen movement says it opposes using Islam as a political ideology, and presents itself as a moderate force advocating cooperation and dialogue.

It is active in the fields of education, dialogue, relief work and media in more than 160 countries around the world, according to the Centre for Hizmet Studies, a London-based non-profit organisation affiliated with Gulen.

Several Gulen-affiliated non-profit groups, including the Journalists and Writers Foundation and the Alliance for Shared Values, have been established, while the movement also organises seminars and conferences. Gulen is said to have millions of followers worldwide, though the exact number is unknown.

But beyond establishing schools, charities and non-governmental organisations, Gulenist sympathisers also have a “dark side,” Turkish columnist Mustafa Akyol recently wrote.

Media reports and investigations have shown the Gulenist to be behind a “covert organisation within the state, a project that's been going on for decades with the aim of establishing bureaucratic control over the state,” Akyol wrote.

Last year, Ankara hired law firm Amsterdam & Partners LLP to investigate the global activities of the Gulen movement, and expose alleged unlawful acts.

“The activities of the Gulen network, including its penetration of the Turkish judiciary and police, as well as its political lobbying abroad, should concern everyone who cares about the future of democracy in Turkey,” founding partner Robert Amsterdam said at the time.

Turkey officially listed the Gulen movement as a terrorist organisation in May.

"We will not let those who divide the nation off the hook in this country," Erdogan said at the time. "They will be brought to account. Some fled and some are in prison and are currently being tried. This process will continue."

‘A very bitter divorce’

But relations between Erdogan and Gulen were not always so volatile.

Erdogan was close to Gulen for decades, and the two leaders were in common opposition to secular Kemalist forces in Turkey.

They also shared the goal of transforming Turkey into a state of “Turkish nationalism with a very strong, conservative religiosity” at its core, said Ariel Salzmann, an associate professor of Islamic and world history at Queen’s University in Canada.

Erdogan and Gulen were “partners in trying to assume power for decades,” Salzmann said.

The leaders shared a common opposition to Kemalist forces in Turkey for many years, and though he did not enter politics himself, Gulen supported the AKP – and thus mobilised his followers – when the party was founded and later came to power.

Members of the Gulen movement were also linked to two notable cases in Turkey – the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer investigations – that looked into alleged attempts to overthrow the AKP government and Erdogan.

The Ergenekon case included the arrest of Ahmet Sik, a journalist who wrote a book about the Gulen movement and the alleged influence it wielded in the Turkish security forces. Critics say the Ergenekon case was merely a pretext to target dissidents.

“It’s a modern, Islamic confraternity,” Salzmann told Middle East Eye about the early Gulen-Erdogan relationship.

“They had common interests and they were complimentary in many ways,” Salzmann added.

Ties between Erdogan and Gulen began to fray when Gulenists in the police and judiciary “became a little too independent,” Salzmann said, and worsened when Gulen himself criticised Erdogan for his handling of the Gezi Park protests in 2013.

Later that year, Erdogan said Gulen and his supporters were trying to bring down his government through a corruption probe that implicated several officials and business leaders with ties to the AKP, and led to the resignation of AKP ministers.

The government has also accused members of the Gulen movement of wire-tapping government officials.

Since that time, Erdogan has repeatedly said Gulen is running a “parallel state” inside Turkey and his government has cracked down on Gulen-affiliated institutions, including the popular Zaman newspaper and Bank Asya.

“I think the idea that there would be someone who would challenge , who disagreed with him slightly, with his ideas and his methods, led to this confrontation, which ended up in the state takeover of all Gulen-related industries,” Salzmann said.

“It’s really a very bitter divorce,” she added.

Gulenist education network

A central way Gulen has extended his influence is by establishing schools inside Turkey and gradually setting up public and private academic institutions in other countries.

According to academic Bayram Balci, these schools all have the same goal: “making new and modern elites capable of modernising Muslim societies”.

“The movement is very modern. They provide modern and generally very secular education, but conservative at the same time,” Balci told MEE, comparing proponents of Gulen-linked education abroad to Christian Jesuits, well known for their missionary work.

“They are elitist, modern, mysterious, and they travel around the world to diffuse their values,” he said.

Balci, an expert on the influence of Gulenist institutions in Central Asia and the Caucasus, told MEE that Gulen first focused on expanding into this region after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

At the time, countries like Albania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and others in Central Asia were more open to foreign – and particularly, Turkish – influence, he said.

The movement is also reportedly tied to about 150 charter schools – public schools that are privately managed – in the United States, though many of these schools dispute any alleged connection to Gulen or Gulenist influence on their operations.

“This denial of affiliation is not unique to these charter schools,” said Joshua Hendrick, a professor at Loyola University in Maryland and author of “Gulen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam in Turkey and the World”.

“What is and what is not an organisation that is affiliated … with the Gulen movement has always been something that has never received a straight answer from those who are being asked that question.”

Hendrick told MEE that since these schools are technically public, they must offer the curriculum requirements set by the districts they are operating in. The schools do not engage in direct religious teachings, but they will all offer a Turkish language option and give students and parents a chance to take a subsidised trip to Turkey.

“They’re far more Turkish in what they’re trying to deliver as a brand alternative. It’s less their Muslimness and more their Turkishness,” Hendrick said.

The Gulen movement aims to accumulate and wield influence, Hendrick explained, with the long-term aim of creating social change back in Turkey. But Gulenists would rather use their influence to support political actors rather than directly participate in politics themselves, he said.

In the US, Gulen-affiliated individuals also extend far beyond the charter schools, and can be found in media, finance, retail, restaurants, law, accounting and IT firms, and even livestock facilities, Hendrick said.

“The schools are just the most glaring and sort of the anchoring of the community, but by no means is it limited at all to schools,” he said.

Behind the coup?

While Erdogan systematically removed alleged Gulenist sympathisers from the police, judiciary and media, the Turkish military “was the last remaining Gulenist stronghold in Turkey,” Dani Rodrik, a professor of International Political Economy at Harvard University, recently wrote.

Rodrik said Erdogan was preparing to purge the army of Gulenist officers, meaning that they “had a motive, and the timing of the attempt supports their involvement”.

But a violent coup is not a regular tactic for Gulenists, Hendrick said.

“Whatever one wants to say about the Gulen movement, it’s not organisationally inept. They have a tremendous capacity to play a long game, to exercise patience, to be clear with their goals for their constituents … And how disorganised and disjointed this all was, how poorly planned, how quickly crushed, just strikes me as curious,” he said.

“It doesn’t seem like it’s their MO at all.”

Meanwhile, Salzmann said Gulen has become a “red herring,” which Erdogan is using to justify cracking down on any perceived opposition inside Turkey and vastly limiting freedoms.

Since the attempted coup, the Turkish government has declared a three-month state of emergency, during which time it will suspend the European Convention on Human Rights.

Turkey has barred academics from leaving the country, closed hundreds of schools, suspended the annual leave for three million civil servants, and arrested, fired or suspended at least 50,000 police, soldiers, judges, teachers and other professionals.

‘Cataclysmic’ impact

While Erdogan has cracked down on anything with Gulenist ties in Turkey, Balci said it has so far been difficult for Erdogan to shutter similar structures outside of the country.

“It is not easy to declare illegal a movement and its schools that you have supported for more than 20 years,” he said.

“In Central Asia, for example, the schools started to make new elites in 1991 when the USSR collapsed, so in 20 years or more, a lot of people went to these schools in perfect legality.”

Still, Hendrick said if Erdogan could prove – to a high, international legal standard – that Gulen was indeed responsible for the attempted overthrow of his government, the impact on Gulenist activities worldwide would be “cataclysmic”.

“It would immediately become that which its critics have said it is and has been for 40 years,” Hendrick said.

“Knowing that there is conclusive proof that this organisation operating in their country overthrew one of their trade partners, I don’t see how that host country continues to allow the operation of that entity.

“It would be existentially cataclysmic for their future if this is proven to be accurate at all.”

Spread the word