Visual journalist Pedro Vega, Jr. had his resignation letter ready. It was dated May 5, a Friday. Ebony still owed him about $10,000 for work he had done as a freelance designer before he joined the staff full-time as creative director in February, trusting the magazine would make him whole, Vega tells CJR.

But on May 4, Vega got a call from the human resources division at Clear View Group, the entirely black-owned Texas-based private equity firm that bought Ebony last year. Ebony was “restructuring,” Vega was told, and he would no longer have a job. He called his boss, Editor in Chief Kyra Kyles, who told him she didn’t know what was going down.

By Friday, the day Vega had planned to resign, the Chicago Tribune reported Ebony was laying off almost a third of its editorial staff and downsizing its Chicago headquarters to consolidate editorial operations in Los Angeles with sister publication Jet.

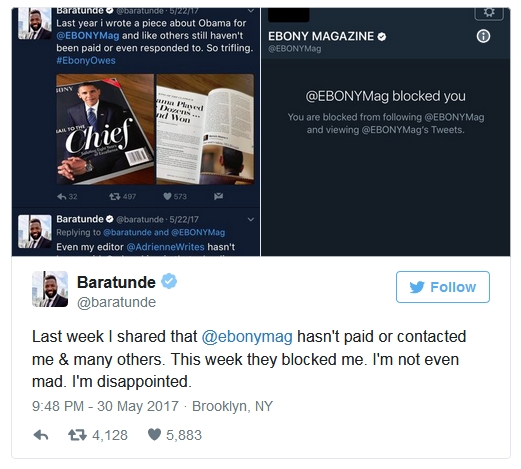

Vega is one of the lucky ones; he has since been paid the $10,000. But plenty of his fellow journalists who worked for the magazine, myself included, are still awaiting checks. More than a dozen writers, most of them black, have broadcast the company’s mistreatment of freelancers on Twitter using the hashtag #EbonyOwes, sharing stories of ignored calls and excuses from Ebony’s accounts-payable department. Fourteen such writers have enlisted the National Writers Union, an industry association representing freelance journalists, to go after Ebony to recover $30,000 the magazine owes them collectively.

Many journalists say their ordeal has been distinctly painful because of their reverence and love for the 72-year-old Ebony brand, which has struggled to retain its relevance in the digital age and among younger audiences. They suspect the publication’s new owners may be taking advantage of their loyalty to the legendary magazine. Adding insult to injury, Ebony’s Twitter account has blocked many of its unpaid writers. “This company is riding a legacy,” Vega tells CJR, “and I don’t know how long you can ride a legacy.”

CJR tracked down Clear View co-founder Willard Jackson via Facebook after several calls and emails to Jackson and other executives went unanswered. In an exclusive interview Saturday, and via a series of text messages Monday, Jackson blamed the magazine’s deep problems on prior ownership. (Johnson Publishing, the family company that owned the title from the beginning, said it wanted out of the publishing business.) Jackson added that Ebony had been slow to shift its focus online and still lacks what he calls “a robust digital platform.”

“It’s unfortunate that it’s gotten to this point with these freelancers,” says Jackson. “But these freelancers, these guys—and ladies—we work with them a lot and we’re going to continue to. They will absolutely be paid in short order here.”

In the Saturday interview, Jackson insisted delays in payments had nothing to do with the company’s finances. But a company statement released over the weekend said that its freelance budget would be raised to prevent future mishaps.

On Monday, when CJR reached out again, Jackson responded via text message: “Prioritizing of the cash flow from the business to cover all the overhead and expenses is what we’ve had to address. That’s why payments have been delayed and that’s also what prompted the layoffs and downsizing.” He declined to discuss his privately held company’s financials in detail.

Jackson says Ebony is the top African American brand in the world, and garners extraordinary loyalty from its base.

He’s right, of course. A lot of black people love Ebony. But love only goes so far for the journalists who make it happen, especially when the object of your affection is slow to cut you a check.

“We’re going to get them paid,” National Writers Union President Larry Goldbetter vows in an interview with CJR. “But the biggest thing really isn’t so much what can we do for them. It’s what they’re doing—standing up together. It’s very easy for a publisher or company to blow people off individually, but it’s a whole different dynamic when they stand up together.”

Goldbetter has no plans to ease up the pressure on the magazine, despite what he described in an interview with CJR as a productive weekend phone call with management. “They told us basically that they intend to pay off everybody within 30 days of the first contact we had two days ago, on Wednesday, so within the month of June.” The bad news, he said, is that “it was very vague, and there was no date for the first check.”

“Why didn’t they cut that check today?” he says.

Liz Dwyer, a Los Angeles-based journalist, is one of the writers who has connected with the union to fight for payments from Ebony. She wrote three stories for the magazine’s February issue about how black Americans can respond to the presidency of Donald Trump, and says she hasn’t been paid for any of them. She’s “had to harass a publication to be paid” in the past, but with Ebony, she fears that talented black journalists, whether long in the tooth or cub reporters, may be hurt in their pockets and morale, and give up on their journalism dreams.

“If they’re saying, ‘You know what, I actually can’t hang on as a freelancer until I get a staff job,’ or ‘Maybe I should switch to public relations,’ or ‘Maybe I should go try to get a job in the communications office at my local college,’ our newsrooms and our publications are losing out on their perspective and their voice,” Dwyer says.

CJR reached out to several other members of Ebony’s management team for this story. The other co-founder of Clear View, Michael Gibson, did not respond to several emails and calls. Neither did Linda Johnson Rice, the daughter of Ebony’s founder, who was promoted to CEO of Ebony Media in March, nor Tracy Ferguson, the editor in chief now at the helm of Ebony and Jet.

***

Ebony, like most media companies, has struggled in the digital age. We all know the basic story of those struggles: Outlets face pressure to transition online, but media models are based on print ad revenue, which has plummeted. Meanwhile, revenue from online advertising hasn’t quite caught up. Is there light at the end of the tunnel for Ebony, or is the publication lumbering toward a tragic end?

Pioneering black publisher John Johnson launched the Ebony brand in 1945, three years after launching Johnson Publishing Company. As the story goes, Johnson couldn’t get a loan from a bank because he was black, and instead used his mother’s furniture as collateral to raise $500 to launch the company. His first publication was the Negro Digest. Ebony would debut three years later, and newsweekly magazine Jet launched in 1951. By the early 1980s, Johnson was worth more than $100 million. He died in 2005.

Cultural historian Ayana Contreras tells me: “Ebony is like the collective family album of black America.”

“Anything that happened that was important to black Americans was often covered in Ebony before it was covered anywhere else,” says Contreras, a producer at WBEZ Chicago’s Sound Opinions.

I am one of those African Americans who grew up revering the brand. And as a black writer, and one who has been through his own spell of #EbonyOwes drama, I can say the mistreatment comes with a particular sting.

From iconic covers framed on the walls of my childhood barbershop to my grandmother’s coffee table and my own coffee table today, Ebony has had a presence in my life for as long as I can remember. That legacy is why I was reluctant to write this article. It’s also why I had to write it, even if it feels a bit, as one unpaid but unwilling to comment Ebony freelancer put it, “messy.”

***

On May 12, at the Chicago Headline Club’s Peter Lisagor Awards in the Chicago Loop, a black reporter I know walked up to me and asked, “What’s going on with Ebony?”

She knew I had written for them as a freelancer because she had seen my proud social media posts. The two of us chatted about the latest news: the layoffs, the freelancer controversy.

Soon we were joined by three other local black journalists. All of us knew people at Ebony—a cherished mentor or former co-worker—and most of us had written for the magazine. It was like we were talking about a relative in hushed tones so as to not be overheard by people outside our family.

I told them my #EbonyOwes story. In January, Ebony published my story about the history of activism in pro football. It was my first time writing for the magazine, and I signed a contract that should have paid me $1,000 within 45 days of my invoice. As I waited for my payment, I took on two other assignments. But more than a month after Ebony was supposed to pay me, I hadn’t seen a dime despite multiple emails to accounts payable.

Frustrated, I emailed print managing editor Kathy Chaney. She advised me to copy her on further emails and said she would look into things, so I did, making another plea to be paid. But a week passed without more information. It was the end of the month, and my rent was coming due.

“I really need you all to cut me a check, please,” I wrote in an email, describing how I felt disrespected by Ebony, and how “In my heart, I want to maintain a good relationship with Ebony.”

But, I wrote, “I feel like I have been taken advantage of.”

“I work hard and I don’t have much, and it’s truly a sad day when something like this happens to somebody like me, a black man who grew up reading this publication.”

My check came within a week. I sent Chaney a text message in late March: “Thanks for having my back!”

Chaney told me she’s been monitoring #EbonyOwes, and that she was one of several advocating for freelancers to get paid before she was laid off in early May. “The editors wouldn’t have continued assigning stories if we knew there were payment problems with the freelancers we were reaching out to. Once we were informed by the freelancers of their payment due, we worked tirelessly, within our power, to get their situations rectified.”

Many of the writers asking for payments don’t have in-house advocates like Chaney.

Freelance editor Adrienne Gibbs, who says Ebony blocked her on Twitter and ignored letters from her lawyer, tells CJR she’s poised to take legal action.

In the past year, she has worked as a special managing editor on three issues of Ebony, including a commemorative issue in November honoring outgoing President Barack Obama, a special Women’s Issue with Michelle Obama on the cover published in March, and the current special music issue on stands now and headlined by Chance the Rapper.

“I brought a lot of writers in, and copy editors into the fold, to work on these issues, on an extreme rush of maybe three or four weeks to turn around major issues,” she tells CJR. “People stopped everything they were doing. Because it was Ebony. Because people love Ebony.”

Ebony still owes Gibbs $10,500, and has been in breach of contract since February, she says. The magazine paid her $7,000 a few weeks ago, but has not responded to further attempts to collect the rest of the money. Gibbs says she has been contacted by at least 16 journalists she enlisted who haven’t been paid for their work.

***

Not all of Ebony’s problems relate to industry-wide challenges in media; plenty of its woes are self-inflicted.

Ebony had 1.9 million subscribers in 1992, but that number is closer to 1.3 million today, according to the company’s 2017 media kit. Subscribers have complained of missing issues. Jackson attributed those delays to Ebony changing printers after the sale, though he declined to elaborate. He says there’s a plan in place to ensure subscribers get their magazines.

“Obviously it’s unfortunate that we’re going through the process of having these delays,” Jackson says. “But they will be resolved, are getting resolved as we speak.”

There’s still a lot more to address: Ebony’s problems go back years. There have been questionable financial decisions (including asset sales and exiting ancillary businesses) and a lack of foresight about shifts in the media landscape. And the organization has scrambled to stay relevant with a younger generation and to make inroads with black millennials at a time when many other media entities compete for their attention, says Charles Whitaker, a former Ebony editor and associate dean of Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University.

One problem that has Ebony playing catch-up now is, “They had no interest in hip-hop culture” as it was emerging in the late 80s and early 90s, says Whitaker, 58, who worked two stints at Ebony. “[The hip-hop generation] to them were the baggy-pant gangsters who did not represent the political respectability that was the hallmark of Ebony. Ebony was primarily the aspirational magazine of the black bourgeoisie.”

Jackson says Ebony’s sister publication Jet hopes to connect with young black readers when it relaunches as a “100 percent millennial focused” publication online, with special quarterly print editions starting this fall.

Ebony has made moves on the digital front, too. In May, Ebony and Jet signed with global entertainment firm William Morris Endeavor “to expand its current print and digital footprint, enhance the brand and utilize the magazines’ over 70 years of archival content.”

Whitaker says Ebony must evolve into a conversation-starter for black Americans on both platforms, print and digital, and should do more to build a digital following and engage audiences in a robust way that can spill over into the magazine. Doing that requires having a strong sense of your audience, and cultivating voices online that touch on hot button issues for Ebony’s current and potential readers.

Contreras, of WBEZ Chicago, sees a “great renaissance of black media that’s happening right now, and a lot of that is being spearheaded in podcasts and other websites.”

“But at the same time there really isn’t this deep-dive journalistic publication of record for black people anymore,” she says. “Ebony could fill that space still, but I don’t know that they’re doing it in the way, personally, I know they have done and could still do.”

Jackson insists that “Ebony will continue to be that authentic voice for African Americans in this country, as it’s always been.”

The brand will have to carry the weight; Ebony has shed many of its other assets over the years. It sold its former headquarters on Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago for $8 million in 2010. A year earlier, it discontinued its Ebony Fashion Fair, which was founded in 1958 by Eunice Johnson, John Johnson’s wife, at a time black models were kept off runways by white fashion designers. The event had a lasting impact not just on black America but on the “Big Four” Fashion Week shows you see in New York City. The Fashion Fair Cosmetics line stayed with Johnson Publishing after the sale to Clear View last year.

Don’t write Ebony off just yet, Whitaker insists.

“Even people of your generation and younger who don’t read it and think of it as their grandfather’s publication still think of it as something to be revered, something of our own, and something that should be preserved,” Whitaker says.

“It becomes,” he says, “how do we take this affinity, this romantic notion that Ebony should exist just because it should exist, how do you build on that?”

Start by paying your damn journalists.

_____________________________________________________

Adeshina Emmanuel is a Chicago-based journalist focused on race, class, inequality, social problems, and solutions who has been published in The New York Times, Ebony, Chicago Magazine, and by ATTN.com. He's a former reporter at the Chicago Reporter, Chicago Sun-Times, and DNAinfo Chicago.

Has America ever needed a media watchdog more than now? Help by joining CJR today.

Spread the word