Of course, House Speaker Paul Ryan famously declared the Affordable Care Act the “law of the land” back in March, only to turn around and pass a repeal bill (the American Health Care Act) on May 4. The Senate then spent months crafting a replacement (the "Better Care Reconciliation Act,") only to see it go down 43-57, with nine Republicans voting no.

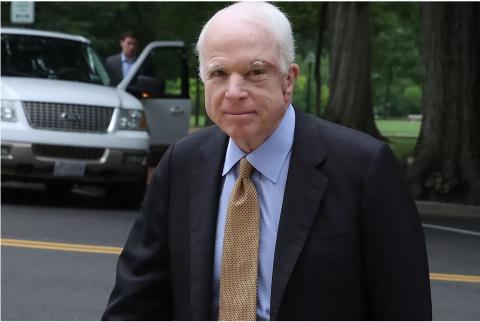

Desperate to take something, anything, to conference committee with the House bill, the Senate tried to pass the Health Care Freedom Act, or “skinny repeal,” which left almost all the spending in Obamacare in place but repealed the individual mandate, delayed one of the taxes, and defunded Planned Parenthood. It fell short by one vote after John McCain decided at the last minute to join Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski in opposing it.

The vote early Friday morning feels like the end of the repeal effort. But it felt that way in March too. Whether this is a temporary setback or a final blow for the repeal effort, though, repeal is far less likely than it was Thursday. Here’s who wins, and who loses, from that shift.

Winner: 16 million Americans who’ll keep or gain health care

The Health Care Freedom Act did not include the budget cuts in prior Obamacare repeal bills. It didn’t cut Medicaid at all — it didn’t roll back the expansion from Obamacare, and it didn’t add new “per capita caps” to cut the program like the House bill did.

The bill didn’t cut insurance subsidies either. People who buy insurance on the exchanges would’ve been able to get the same tax credits they’ve been getting for the past three years.

But it still would have reduced insurance coverage, to the tune of 16 million Americans, 15 million in the first year of implementation alone. In 2018, under the bill, 6 million people would've lost employer-based insurance, 6 million would've lost coverage through the marketplaces and other individual/nongroup options, and 3 million would've lost Medicaid. Over time, the coverage loss would shift, until by 2026 the biggest effect would be reduced enrollment in Medicaid.

This was primarily a result of getting rid of the individual and employer mandates under Obamacare. A skeptic of the law could argue that you're just freeing Americans to buy health care if they want it, and to decline if they'd rather not. Indeed this was then-Senator Obama's argument for much of the 2008 primaries, when he opposed an individual mandate while Hillary Clinton touted the idea.

But the fact is that many people hurt by the law wouldn’t have been healthy people choosing they didn’t need coverage. They would be sick people who were still trying to buy insurance as all the healthy people left. They’d be paying higher and higher premiums as the risk pool got sicker and sicker, possibly leading to a “death spiral” where insurance for them simply became unaffordable or unavailable.

And it’s very hard to see how the millions of Americans who wouldn’t get on Medicaid in the absence of a mandate would be better off. Medicaid has no premiums or deductibles. The mandate pushed people to sign up for this free insurance offered to them, insurance that appears to work and improve health. Without it, fewer will sign up; those who don’t would be worse off.

Killing skinny repeal meant all this didn’t come to pass. It meant that Americans benefiting from the lower premiums caused by the individual mandate could keep benefiting, and that people in the future who might need the mandate to be nudged onto insurance will be able to lead healthier, more financially secure lives.

Winner: Disabled Americans and everyone else who relies on Medicaid

For most of the past year, “Obamacare repeal” was synonymous with “Medicaid cuts.”

To some degree, this had to be true. Obamacare’s biggest coverage gains came via an expansion of Medicaid; repealing Obamacare necessarily meant reversing that, in whole or in part. But the AHCA and BCRA, the major House and Senate health bills, went further. They changed the entire structure of the Medicaid program using a policy known as a “per capita cap.”

Currently, the federal government matches state spending on Medicaid, offering about $1 to $2.79 for every dollar states spend on it. Poorer states get a bigger match. But the BCRA would change all that. The AHCA and BCRA would cap the state match at a set amount of money per person and grow it using a set formula. The BCRA used normal inflation.

Inflation grows far more slowly than Medicaid costs are expected to grow right now. So switching to a per capita cap and tying increases to CPI is essentially a federal cut to Medicaid amounting to hundreds of billions over 10 years. In total, the CBO found that the last Senate bill cut Medicaid by $772 billion over 10 years — and by much more over a longer time horizon.

A per capita cap is at least somewhat responsive to changes in Medicaid enrollment — unlike a block grant, which gives states a set amount of money, it gives them a set amount of money for every person who’s eligible. But it could lead to cuts in some other ways as well. Take a state like Florida that’s aging fast. The BCRA includes separate caps for different groups of beneficiaries — the elderly, disabled, non-elderly adults, etc. — so states can’t get more money by dumping lots of seniors in favor of 24-year-olds.

However, there is still a lot of variation in cost within those categories. A state might be motivated to kick off older seniors and focus enrollment on younger ones. There are some federal requirements as to whom states must cover, but they only go so far, and most states now provide additional coverage that they can roll back.

This helps explain why disability rights activists are appalled by the per capita cap plan, and have been aggressively protesting the Senate and House bills; dozens of activists, many with the group ADAPT, have been arrested for protesting at Senate offices and elsewhere on the Hill.

“People with disabilities who rely on home- and community-based services through Medicaid — such as personal-attendant care, skilled nursing, and specialized therapies — could lose access to the services they need in order to live independently and remain in their homes,” the Center for American Progress’s Rebecca Vallas, Katherine Gallagher Robbins, and Jackie Odum note.

Skinny repeal didn’t include these provisions. But its entire purpose was to go to conference with the House bill, and the likely conference report could’ve included the same harsh Medicaid bills that were so horrifying in earlier version of the AHCA and BCRA. Skinny repeal didn’t itself include Medicaid cuts, but it was still a vehicle for Medicaid cuts.

Accordingly, skinny repeal’s defeat is a win for disability rights activists and everyone else relying on Medicaid, and fighting to preserve it in the face of the repeal effort.

Winner: Barack Obama’s legacy

Here’s an excerpt from a piece I wrote on November 9, the day after the presidential election, predicting what Donald Trump and Paul Ryan would do to the Affordable Care Act with their newfound governing majority (emphasis mine):

There is now a governing majority capable of repealing Obamacare. All of it.

Republicans will almost certainly control the Senate, and definitely control the House, and while the law took a filibuster-proof majority to pass, House Budget Committee Chair Tom Price has designed a bill that would repeal it but work through the budget reconciliation process, which requires a simple majority in the Senate. Price's bill would end the Medicaid expansion and repeal tax credits for low-income Americans. It would repeal the taxes used to finance the law and its mandate. This plan would, according to the Congressional Budget Office, cost 22 million people health insurance.

There’s some reason to suspect the Republicans in Congress wouldn’t go full steam ahead. It’s hard to deny 22 million people health insurance without paying an electoral price for it. They could do the transition gradually, or phase out Medicaid expansion first, since Medicaid recipients are poor enough that they rarely vote for Republicans anyway. But after six years of Republican pledges to repeal and replace, it’s hard to imagine the first part of that equation not happening.

In retrospect, the only part of that assessment that really held up was the caveat. Today the odds of a meaningful repeal package passing Congress are barely higher than they were when Obama himself was president.

That could still change, of course. McConnell could decide to take up another repeal option. Republican Sens. Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy have a plan to devolve Obamacare monies to the states to spend as they see fit; Mark Meadows, leader of the House’s influential conservative Freedom Caucus, is reportedly a fan.

But one thing recent months have taught us is that getting 50 out of 52 Senate Republicans to agree to a package that denies insurance to tens of millions of Americans is really, really tough. Murkowski and Collins, the caucus’s least right-wing members, are heavily resistant. And depending on the form the bill takes, Republicans could also lose conservatives like Mike Lee or Rand Paul, or Republicans from Medicaid expansion states like Dean Heller or Rob Portman (whose votes for skinny repeal appeared to owe a lot to its preservation of the Medicaid expansion).

It might be that McConnell and Ryan decide it’s time to cut their losses and move on to tax reform, leaving the insurance expansions achieved by Obama intact permanently. That’s great news for people with coverage — and good news for Obama’s historical reputation.

Loser: medical device manufacturers

Obamacare involved raising a lot of taxes. It taxed rich people on their investment income and wages. It raised taxes on health insurance companies and tanning salons and brand-name pharmaceutical drugs. And, of course, it raised taxes on medical device manufacturers, the producers of goods like X-ray and MRI machines and pacemakers (devices sold via retail, like hearing aids, are exempt).

Senators from states with large medical device industries, including otherwise liberal members like Elizabeth Warren and Al Franken, have been pushing to repeal the tax for years. And if skinny repeal had passed and become law, they would’ve gotten their wish for a few years. The ultimate “skinny” bill that came up for a vote would’ve kept literally every Obamacare tax in place but repealed the medical device tax for three years.

That wasn’t a final victory for the industry. But it was a big one. Republicans were willing to vote for a bill that kept taxes on capital gains and dividends in place. They were willing to keep a big tax on health insurers. They were willing to add 0.9 points to rich people’s payroll tax rates. What they weren’t willing to do is let medical devices be taxed. Medical device tax repeal became a central element of any Republican bill, just like repealing the individual and employer mandates.

So while the failure of skinny repeal is bad news for the health care industries and high earners who hoped to get tax cuts out of whatever emerged from conference committee, it’s especially bad news for medical device manufacturers, who were all but guaranteed tax relief from the passage of any legislation.

Loser: Mitch McConnell

Mitch McConnell’s reputation has always been that of a master tactician.

He was the guy who in 2009 convinced a soundly defeated rump Republican caucus of only 41 members (40 after Arlen Specter defected) to hold the line against all of President Obama’s initiatives. He got all but three members of his caucus to vote against Obama’s stimulus package and the Dodd-Frank financial reform act, and every single one to vote against Obamacare.

Once his colleagues in the House retook a majority, McConnell worked with them to force trillions in budget cuts, first in the 2011 spending fight and then in that summer’s debt ceiling showdown. He held the line against countless executive and judicial nominations until Democrats finally went nuclear and eliminated the filibuster for those in 2013. And against all odds, he was able to keep Obama from replacing Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court, and blew up the filibuster for that too when necessary to get Trump’s pick approved.

It’s a fairly impressive résumé. Whether you loathe or admire it, McConnell’s defeat of Merrick Garland’s Supreme Court nomination was an unprecedentedly successful form of Senate obstruction that no leader before him had even attempted to pull off.

But as Vox’s Andrew Prokop notes, McConnell really doesn’t have a major legislative achievement to call his own. He was able to disrupt the passage of Harry Reid’s major achievements (Obamacare, Dodd-Frank, the stimulus) but not prevent it. At the very least, with an allied president and a Senate majority, he should be able to repeal some of what Obama and Reid achieved.

Except McConnell has shown he can’t do that. It became very clear that he couldn’t repeal Obamacare in its entirety, both because of reconciliation rules and because plenty of Senate Republicans considered that a bridge too far. And now it’s clear that he can’t even repeal it in limited form, either. Skinny repeal was an exceptionally narrow subset of Obamacare repeal, and even it caused three Republican defections, enough to kill the effort.

McConnell hasn’t accomplished nothing in his first six months under unified Republican governance. He has seated a Supreme Court justice and repealed plenty of Obama-era regulations under the Congressional Review Act. But he has yet to pass major legislation, and he’s running out of time.

Dylan Matthews is Vox Minister Without Portfolio. Email. Twitter. Subscribe to Dylan Matthews.

Spread the word