Thirty-eight years ago, on November 3, 1979, 35 heavily armed members of the Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party drove nine vehicles through the city of Greensboro, North Carolina, and opened fire on a multiracial group of demonstrators who were gathering at a Black housing project in preparation for an anti-Klan march. In the most deadly 88 seconds in the history of the city, the KKK and Nazi marauders fired over 1,000 projectiles with shotguns, semi-automatic rifles and pistols, leaving five of the march leaders dead and seven other demonstrators wounded. Most of the victims were associated with the Communist Workers Party (CWP) -- a militant, multiracial organization which had been organizing in the South against the Klan.

The Greensboro police, the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) were all aware of the plan to attack the march. However, no law enforcement officials were present except for a police informant-provocateur, Edward Dawson, who led the caravan into the housing project, and his control agent, Jerry "Rooster" Cooper, a Greensboro intelligence detective who followed the caravan and reported on its progress to the Greensboro police. Four television crews were on hand and captured the attack on video.

Greensboro's official position was that the CWP had sought a confrontation with the Klan and were responsible for the "shootout." The city declared a state of emergency in response to the funeral march and quickly issued a report absolving its police department of any blame.

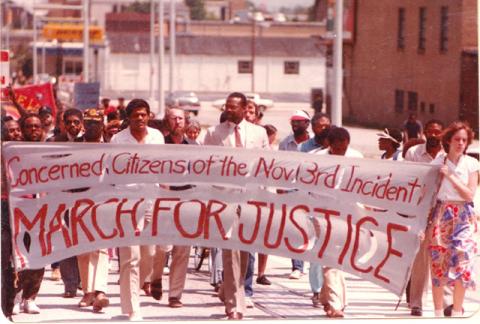

Out of the violence emerged the Greensboro Justice Fund, which was organized by the widows of the victims and was supported by many organizations and people across North Carolina and the country. The public outcry and the shocking video tape evidence helped compel the reluctant local district attorney to obtain indictments against six of the Klan and Nazi members on murder charges.

The six-month-long murder trial began in the summer of 1980, with the chief prosecutor making anti-communist remarks to an all-white jury. The lawyers for the Nazi and Klan defendants used every emotional weapon at their disposal -- anti-communism, racism and patriotism, wrapped around a self-defense claim. The jury acquitted all six defendants.

The acquittal fanned the flames of outrage. The decidedly unsympathetic Reagan Department of Justice originally resisted this pressure, but finally, in March of 1982, the DOJ convened a special grand jury, and, a year later, obtained civil rights conspiracy indictments against nine Klansmen and Nazis. This trial began in January of 1984. The jury was secretly selected and was again, all white. The Klan and Nazi lawyers argued that their clients' motivation was patriotic anti-communism rather than racism. After a three-month trial, the jury acquitted all of the defendants.

On the first anniversary of the massacre, the Greensboro Justice Fund had filed a civil rights suit on behalf of the 16 victims. As plaintiffs, the victims alleged a broad-based conspiracy by the Nazi and Klan defendants under the 1871 anti-Klan Act, which provided victims of racially motivated conspiracies the right to sue the conspirators for money damages. They also alleged that the law enforcement and informant-provocateur defendants officially encouraged and participated in the conspiracy, and that they conspired to cover up their involvement. Their complaint also incorporated newly revealed information that informant-provocateur Dawson had obtained the demonstrators' march plans from the Greensboro police and used them to plot the attack, and that ATF undercover agent Bernard Butkovich had infiltrated the Nazis and had encouraged them to bring weapons to Greensboro.

As the civil suit proceeded, the depth and contours of official involvement became even clearer, revealing that Dawson had also been a longtime FBI agent provocateur in the Klan and had encouraged other acts of violence by his longtime associate, Grand Dragon Virgil Griffin, with whom he planned the November 3 attack. It was also revealed that Dawson had not only been acting with the knowledge of the Greensboro police in planning the attack, but had also informed his FBI contact that violence was likely on November 3, and that Greensboro police had been informed that the Klan was coming to Greensboro with a machine gun "to shoot up the place."

This newly discovered evidence also showed ATF provocateur Butkovich had informed his superiors of the Nazis' plan for violence and of their possession of several high-powered weapons, and that Klansman Jerry Paul Smith had bragged at the Nazi planning meeting on November 1 that he had manufactured a pipe bomb that "could work good thrown into a crowd of n*****s." Butkovich's testimony further showed that his encouragement of violence was pursuant to ATF policy and with his superior's advice and consent.

The civil rights case went to trial in March of 1985. The judge examined more than 300 potential jurors. Most of the prospective white jurors exhibited a great degree of racism, anti-communism and tolerance for the Klan, so the judge was compelled to disqualify more than 250 jurors. Consequently, the selected jury included a Black man who had participated in civil rights demonstrations, and had boldly said in voir dire that he "can't respect any man who has to hide his face to express his beliefs."

The 10-week civil trial had numerous moments of high drama, as the victims presented their case of conspiracy, back dropped by the news video that chillingly showed the murderous attack. One of the most dramatic scenes came late in the trial. The victims' lawyers called victim Paul Bermazohn to the stand. He told of his background as the son of Holocaust survivors, his role in organizing the "Death to the Klan" rally, and how he was shot in the head. Next was Roland Wayne Wood, who was one of the main shooters. He was confronted with some of his prior anti-Communist and anti-Semitic statements, his previous wearing of a "Eat lead you lousy Red" tee-shirt to court, a Nazi song that included the chilling refrain "kill a Commie for Christ," and the five white skulls that he had pinned to his lapel. His denial that the skulls represented the five slain demonstrators rung coldly hollow.

On June 7, 1985, the jury returned a compromise verdict. After nearly six years and three trials, a southern jury had finally convicted a good number of the main actors in the November 3 massacre and had found a conspiracy between police officials, their provocateur, and several of the Klan and Nazi killers. An intense six-year struggle -- waged by the widows, the families, the survivors and numerous political, religious and community organizations, and prosecuted by people's lawyers, law students and paralegals -- had resulted in a seldom seen victory against the Klan and the police. The Klan could no longer claim, as they had previously, that November 3 stood for the principle that they could kill Black people and communists with complete immunity.

The verdict was national news, with the New York Times editorializing that "the recompense for the victims may be limited as well as late, but this is no time to complain about inadequate justice. The criminal acquittals set back American principles of law and civil rights; the civil verdict goes a long way to reassert them." Appropriately, a picture of the plaintiffs walking triumphantly out of the courtroom with their hands clasped together over their heads ran on the front page of the Sunday Greensboro News and Record. The verdict placed the Greensboro massacre in the long-running historical context of racist Klan violence that was all too often fomented by FBI and police provocateurs, and countenanced by law enforcement officials who would make themselves conveniently absent.

Now, in the era of Trump and a white supremacist resurgence, the lessons taught by the Greensboro case are particularly important to remember. The Charlottesville case is a prime example of this history repeating itself -- the coming together of emboldened white supremacist organizations, heavily armed and looking to engage in deadly violence; a militant opposition to those organizations; and law enforcement agencies conveniently enabling the white supremacists and looking the other way while they wreak their bloody and murderous terrorism. The reactions of Attorney General Jeffrey Beauregard Sessions and President Donald Trump to Charlottesville foreshadow an official response that may well make the DOJ's response in Greensboro look tame by comparison -- they have already started to blame the victims and promise an aggressive investigation of the counterdemonstrators.

This response is in keeping with the tenor of this administration, under which white supremacy is finding full-throated encouragement and official protection in the halls of power. Whether it be the Muslim ban, taking the "gloves off" local police, targeting "Black Identity Extremists" -- a move that smacks of the FBI's deadly COINTELPRO program -- defending Confederate symbols of slavery, or moving to reinstate draconian sentencing laws, the dog whistle of officially countenanced racism has been supplanted by an overt ideology of white supremacy.

That being said, Greensboro offers other, more positive lessons as well. Not only did courageous militants oppose the resurgence of white supremacy in North Carolina, they refused to be silenced even after five of their brothers and sisters were murdered and many others were injured and terrorized. Instead, they came together with other progressive activists, lawyers, legal workers and journalists to successfully change the official Greensboro narrative; to fight for some modicum of justice; to continue to oppose white supremacy; and to take on the governmental leaders and agencies who enabled, encouraged and covered up the wanton white supremacist violence.

On the anniversary of the Greensboro Massacre, let us remember the work of these brave activists, and let us draw strength from them as we move forward in the current repressive political climate to continue the crucial fight for racial justice.

Copyright, Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission. Reprinted with permission.

G. Flint Taylor, a founding partner of the People's Law Office in Chicago, has been counsel in numerous important civil rights cases over the past 48 years, including the Fred Hampton assassination case, the Jon Burge torture cases and the Greensboro civil case.

Spread the word