Readers of the May 24, 1796 Pennsylvania Gazette found an advertisementoffering ten dollars to any person who would apprehend Oney Judge, an enslaved woman who had fled from President George Washington’s Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon. The notice described her in detail as a “light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy black hair,” as well as her skills at mending clothes, and that she “may attempt to escape by water … it is probable she will attempt to pass as a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage.” She did indeed board a ship called the Nancyand made it to New Hampshire, where she later married a free black sailor, although she was herself never freed by the Washingtons and remained a fugitive.

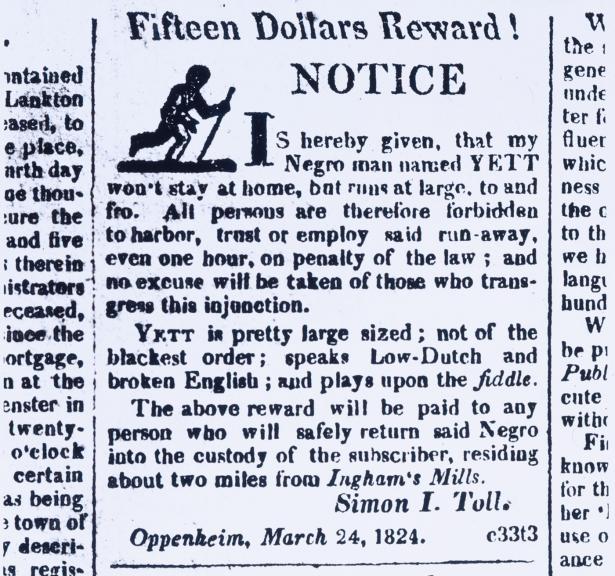

The advertisement is one of thousands that were printed in newspapers during colonial and pre-Civil War slavery in the United States. The Freedom on the Move (FOTM) public database project, now being developed at Cornell University, is the first major digital database to organize together North American fugitive slave ads from regional, state, and other collections. FOTM recently received its second of its two National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) digital humanities grants.

The Freedom on the Move project from Cornell University (screenshot by the author for Hyperallergic)

“Ironically, in trying to retrieve their property — the people they claimed as things — enslavers left us mounds of evidence about the humanity of the people they bought and sold,” Dr. Mary Niall Mitchell, professor of early American history at the University of New Orleans and one of the three lead historians on FOTM, told Hyperallergic. The other two historians are Joshua Rothman of the University of Alabama and Edward E. Baptist (author of the 2016 The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism) of Cornell University.

As with the ad for Oney Judge, these classifieds did not only include meticulous information on appearance, but also skills, personalities, mannerisms, scars from whips or brands, history of sale, and where they might flee to based on the locations of friends and family. While the database is still in progress, examples of the ads are being shared on the @fotmproject Twitter account. One for a woman named Sabina who fled with her son describes her “high cheek bones” and that she “walks parrot-toed”; another for a man named Griffin states he is “a very light mulatto (in fact some persons would mistake him for a white man).” An ad from 1840 offers a $20 reward for Aaron who “has been absent some weeks — he is about 27 years of age, 5 feet 7 or 8 inches high, and is a light mulatto; has a scar on one of his cheeks; speaks French and English, and stammers when speaking; is a painter by trade, and is no doubt at work on some of the buildings about the city.”

“For some, this may be the only place something about them survives, in any detail, in the written record,” Mitchell said. She added that the huge volume of ads — with around 100,000 involved in FOTM — expands on the history of resistance against slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some of the ads represent people who escaped more than once. “The Underground Railroad was just one among many efforts on the part of enslaved people to liberate themselves,” she said. “Many enslaved people ran without an organized network of free people to help them.”

Crowdsourced data tags and transcriptions will be a major part of FOTM’s public engagement. Database users can then examine spatial patterns and compare trends over time. “Combining all of these ads together in one searchable database will allow us to ask new questions about the enslaved population over time,” Mitchell explained. “At what time of year were enslaved people most likely to run? What places did they frequent? What skills did they have? How many could read and write? Or were likely to ‘pass’ for white, or claim to be free? What did they wear? Where were they suspected to be hiding and with whom? Under what circumstances did women run away? We can also learn more about the ethnicity of the enslaved population, which is to say, where they or their family may have originated — from a particular nation in Africa, for instance — or whether they were Creole or American.”

The Runaway Slaves in Britain project at the University of Glasgow is similarly examining the history of slavery in the UK through advertisements from 18th-century newspapers. There are first-hand narratives of slavery — such as Frederick Douglass’s 1845 memoir and Solomon Northup’s 1853 Twelve Years a Slave — yet overwhelmingly millions of voices are missing from recorded American history. FOTM aims to deepen our understanding of the experiences of enslaved people, and slavery’s role in the development of the country. As Mitchell stated, “Through these individual stories, we aim to help people in the present connect with the past and with the plight of those who suffered and resisted slavery.”

Allison C. Meier is a former staff writer for Hyperallergic. Originally from Oklahoma, she has been covering visual culture and overlooked history for print and online media since 2006. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.

Hyperallergic is a forum for serious, playful, and radical thinking about art in the world today. Founded in 2009, Hyperallergic is headquartered in Brooklyn, New York.

Spread the word