Now that Tim Geithner has resigned as US Treasury secretary, it is time to survey the damage wrought from four years of his approach to the financial crisis. The “Geithner doctrine” made the preservation of the largest banks, no matter the consequences, a top priority of the US government. Aside from moral hazard, it has also meant the perversion of the US criminal justice system. The US faces a two-tiered system of justice that, if left unchecked by the incoming Treasury and regulatory teams, all but assures more excessive risk-taking, more crime and more crises.

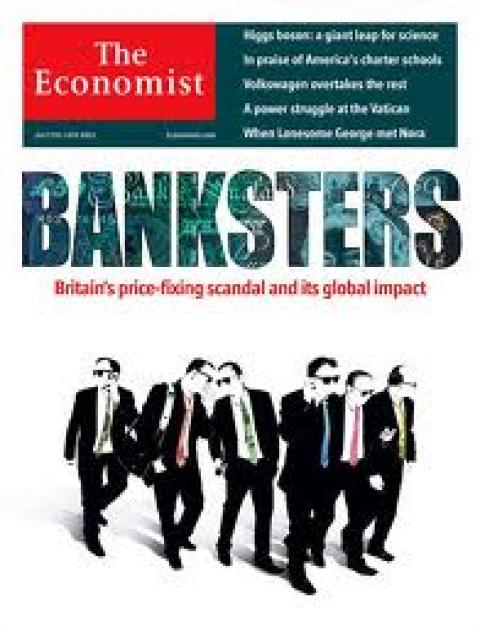

The recent parade of banking scandals, such as the manipulation of Libor rates by Barclays, Royal Bank of Scotland and other major banks, can be traced back to the lax system of regulation before the financial crisis – and the weak response once disaster struck.

Take the response of the New York Federal Reserve to Barclays’ admission in 2008 that it was submitting false Libor rates and was not alone in doing so. Mr Geithner’s response was to in effect bury the tip. He sent a memo to the Bank of England suggesting some changes to the rate-setting process and then convened a meeting of regulators where he reportedly described only the risk but not the actual manipulation of the rate. He then put the government imprimatur on the rate via bailout programmes. His inaction helped permit a global crime to continue for another year.

When it was UBS’s turn to settle its Libor charges, even though a significant amount of the illegal activity took place at the parent company level, only a Japanese subsidiary was required to take a plea. Eric Holder, US attorney-general, demonstrated his embrace of the Geithner doctrine (a phrase coined by blogger Yves Smith) in explaining the UBS decision. He said that a more aggressive stance against the parent company could have a negative “impact on the stability of the financial markets around the world”.

This week we saw the latest instalment of the saga. In fining RBS £390m, the DoJ only indicted one of the bank’s Asian subsidiaries, avoiding the more damaging result that would have stemmed from charging the parent company.

Instead of seeking deterrence and justice, the US government increasingly appears to have fully absorbed the Geithner doctrine into its charging decisions by seeking a result that has a minimal impact on the target bank but will generate the best-looking press release. Some banks today are still too big to fail – and they are still too big to jail.

The lack of robust enforcement is of course not limited to the Libor scandal. It was seen in the recent settlement talks with HSBC, when Treasury officials reportedly pressed the DoJ to consider the broad economic consequences that would follow an indictment. After hearing these arguments the DoJ chose not to criminally charge HSBC.

And, of course, it is seen in the stunning dearth of criminal prosecutions arising out of the crisis. This was all but preordained given who the government turned to when the crisis struck: the same captured regulators who had blindly advanced bankers’ self-serving calls for a “light touch” before the crisis and who unsurprisingly embraced the Geithner doctrine afterwards. Having done so, of course, there would be no criminal prosecutions while the banks still teetered on the brink of collapse. The risk of causing them to fail, and thereby undoing all of the bailout efforts, was too high.

But that these arguments continue to resonate with officials in 2013 shows that the Geithner doctrine, perhaps justified by the conditions in 2008-09, has planted deep roots in our system of government.

This forbearance will have potentially devastating long-term effects, as each settlement on favourable terms reinforces the perception that, for a select group of executives and institutions, crime pays. It is only rational. They know that they will get to keep all of the ill-gotten profits if they go undetected, and on the small chance that they’re caught, most probably only the shareholders will pay – and only a relatively minor fine at that. The lack of meaningful consequences for those committing these frauds encourages future fraudulent conduct. Ultimately, the financial crisis was a game of incentives gone wild, and the lack of accountability in the aftermath of the crisis has only reinforced those bad incentives.

Breaking those incentives requires ditching the Geithner doctrine, which has led to the banks becoming even larger and more systemically significant than they were before the crisis. As a result, the DoJ’s fear of destabilising the global economy through aggressive prosecutions may indeed be well-founded. But that must not be the end of the story.

To reclaim our system of justice, the global threat posed by the failure of any of our largest financial institutions must be neutralised once and for all. They must be reduced in size, their safety nets must be dramatically constricted and their capital requirements enhanced far beyond the current standards. Then, and only then, can the same set of rules apply to all.

Neil Barofsky is the former special inspector-general of the troubled asset relief programme (TARP) and is currently a senior fellow at NYU School of Law. He is the author of ‘Bailout’, released in paperback this week.

Spread the word