"Mexico will likely remain stuck in this trap until it makes the necessary public investments in infrastructure, research and development, and education that will enable it to restore normal economic growth and development. Mexico's next government, whoever heads it, should consider a new policy regime."

Executive Summary

In December 2012, leaders of Mexico’s then most prominent political parties agreed on the “Pact for Mexico” in the Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City. It was billed as charting a new path for Mexico and its economy, and was signed by the largest political parties at that date: President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI); Jesús Zambrano Grijalva, national president of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD); María Cristina Díaz Salazar, interim president of the Executive Committee of the PRI, and Gustavo Madero Muñoz, national president of the National Action Party (PAN).1

This paper briefly examines whether there has been progress toward the Pact’s goals since it was signed, and whether any measures taken since then — including current economic policies — are likely to help Mexico break out of its long economic slump. In the twenty-first century, Mexico has ranked 18th out of 20 Latin American countries in the growth of its income per person.

It is clear from the available data that there is little, if any, progress toward the goals put forth in the Pact. For example:

• The Pact promised to increase growth to more than 5 percent annually. Real GDP growth averaged just 2.4 percent annually, and does not appear to be making progress toward the 5 percent goal. Over the same period, real per capita GDP growth averaged only 1.4 percent annually.

• The Pact promised to increase investment to over 25 percent of GDP. Gross fixed capital formation fell from 22.3 percent of GDP in 2012 to 20.5 percent in 2017.

• The Pact also promised to reduce inequality: the income share of the top 10 percent, already high at 34.9 percent in 2012, increased to 36.3 percent in 2016. Meanwhile, the share of income received by the poorest 10 percent remained the same at just 1.8 percent

• The Pact promised to reduce poverty. The national poverty rate has seen a slight drop between 2012 and 2016, from 45.5 percent (of population) to 43.6 percent. However, this was not enough to lower the absolute number of people living in poverty, which rose very slightly to 53.4 million in 2016, from 53.3 million in 2012.

• Public investment in state oil company Pemex was about 2.0 percent of GDP (312 billion pesos) in 2012, and fell to 0.9 percent of GDP (191 billion pesos) by 2017.

• The government’s oil revenue collapsed, falling from 1,386 billion pesos in 2012 to only 827 billion pesos in 2017, a fall from 8.8 percent of GDP to 3.8 percent of GDP. This is a very large negative fiscal shock.

• On the positive side, underemployment has come down somewhat from 8.4 percent in 2013 (yearly) to 6.8 percent in the first quarter of 2018. (In Mexican statistics, underemployment is a much better measure of the state of the labor market than unemployment — see below.) However, the economic growth that reduced underemployment was driven mainly by consumption, which accounted for an average of 76.9 percent of real GDP growth from 2013 to 2017.

There are a number of reasons to believe that the failure to achieve any significant progress toward the Pact’s goals in the first five years is not simply a result of insufficient time, but rather the continued application of a flawed set of policy choices. Among the reasons:

• The government engaged in a fiscal consolidation plan in which spending fell from 24.8 percent of GDP in 2014 to 20.1 percent of GDP (projected for 2018). This is a very large decline in government spending, something not seen for example in the last 70 years in the United States.

• The cyclically adjusted primary fiscal balance, which attempts to adjust for the business cycle, tightened by 2.6 percentage points during this time.

• The government’s commitment to further fiscal consolidation makes it very difficult for it to make the public investments it might need in infrastructure, education, and research and development in order to deliver on the Pact’s promises to increase growth or reduce inequality or poverty. All of these levels of public investment are currently quite low.

• Beginning in December 2015, the Mexican Central Bank raised interest rates quite aggressively, more than doubling the rate of 3 percent to 7.5 percent by February 2018. There is evidence (see below) that this may have been much more monetary tightening than needed.

• Mexico’s hyperliberalization of its financial markets has made it particularly vulnerable to contagion and economic shocks from the world economy, and especially from the United States — upon which it also depends for 80 percent of exports.

Mexico was once a fast-growing developing economy, with its income per person nearly doubling between 1960 and 1980. It thereafter went into a long slump and has never come close to recovering its prior rates of growth and development. This paper argues that vitally important policy choices have been responsible for this long-term failure.

Mexico currently faces serious downside risks from the global economy, as the US Federal Reserve is on track to raise interest rates four times this year, and more in 2019. The Fed’s interest rate hikes can have a severe impact on the Mexican economy if it draws away sufficient capital flows. This was seen in the 1994–95 peso crisis, where Mexico lost 9.5 percent of GDP in a downturn that was triggered by the Fed’s cycle of interest rate hikes at the time; and in 2013, when the country’s hyperliberalization of financial markets also made it vulnerable to the Fed’s tapering of quantitative easing in 2013. These hyperliberal financial markets make Mexico more vulnerable than it otherwise would be to turbulence in international financial markets that may already be beginning in this Fed tightening cycle.

Thus Mexico, under the current long-term policy regime described above, is committed to paying down the public debt when growth picks up even slightly; and when there are storm clouds on the horizon (which also include the turbulence of current relations with the United States, and the uncertainty of NAFTA renegotiation), fiscal and monetary policy become even more of a drag on economic growth. Mexico is therefore caught in a trap of low investment and low growth, without making the necessary public investments in infrastructure, research and development, or education. Without such investment, it cannot maintain its international competitiveness (even in US markets with respect to China), boost long-term productivity growth, or even maintain the necessary fiscal revenues from Pemex — not to mention reducing poverty or inequality.

Introduction

Mexico has suffered from a long-term economic failure that began in 1980 and has never come anywhere close to recovering its prior rate of economic growth or development. From 1960 to 1980, living standards rose rapidly, with income per person nearly doubling; in the two decades that followed, it increased by just 9 percent.2 In the twenty-first century, Mexico’s economic performance improved somewhat but still lagged behind most of Latin America, leaving it 18th of 20 countries in economic growth since 2000, with only Belize and Venezuela doing worse.3

Many of Mexico’s current troubles, including the rise to power of drug cartels and the tens of thousands of murders and disappearances, the deep corruption of the state, and the associated political discontent, result at least partly from this long-term economic failure. Real wages today are barely above their level of 1980. Poverty has been widespread and persistent; if we measure from the beginning of NAFTA, which was supposed to jump-start the Mexican economy, the Mexican national poverty rate was actually higher in 20144 than it was when NAFTA was implemented in 1994. This meant that an additional 20.5 million Mexicans were living in poverty in 2014, as compared to 1994.5

There are multiple causes of this prolonged economic failure, including NAFTA itself, which helped lock in a set of inappropriate economic policies that began in the 1980s and added new ones. About 5 million Mexican family farmers were displaced from agriculture between 1991 and 2007.6 Mexico also had the misfortune of tying its economy to that of the United States, just as the United States was about to embark on the building of the two biggest asset bubbles in world history (the stock market bubble in the late 1990s and the housing bubble post-2002), followed by the Great Recession.

The accession of China to the WTO in 2000 put Mexico into direct competition for the US market with a country that had a robust industrial policy, including control over its exchange rate (as opposed to Mexico’s inflation-targeting regime), vastly more spending on research and development, and government control over its financial system. Mexico’s hyperliberalization of its financial system also presented new instabilities: as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has pointed out, the country’s “deep and liquid foreign exchange and domestic equity and sovereign bond markets can serve as an early port of call for global investors in episodes of financial turbulence and hence are susceptible to risks of contagion.” 7 This became evident in May 2013, when the US Federal Reserve announced that it was going to “taper” its quantitative easing, provoking flashbacks of the 1994 peso crisis (which was also caused by a tightening of the Fed’s monetary policy). In 2013, Mexican growth fell to just 1.4 percent as a result of this “taper tantrum.”

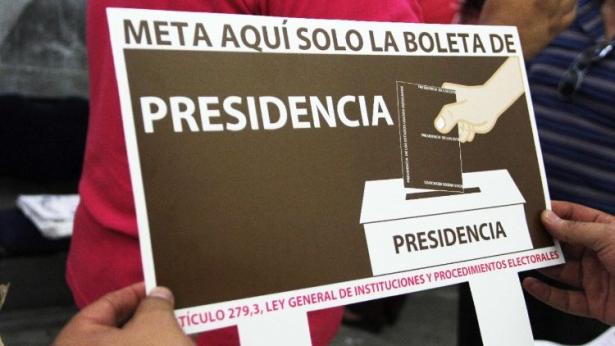

In December 2012, leaders of Mexico’s then most prominent political parties agreed on the “Pact for Mexico” in the Chapultepec Castle in Mexico City. It was billed as charting a new path for Mexico and its economy, and was signed by the largest political parties at that date: President Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI); Jesús Zambrano Grijalva, national president of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD); María Cristina Díaz Salazar, interim president of the Executive Committee of the PRI, and Gustavo Madero Muñoz, national president of the National Action Party (PAN). The only leader of a significant political party who did not sign the Pact was Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the Morena party, who is currently favored to win the July presidential election. The Morena party was not yet formed at the time of the Pact; however, López Obrador subsequently denounced the Pact.8 He has said he favors a more developmentalist economic program, including some industrial policy and a somewhat expanded social safety net. The Pact pledged to institute policies that would usher in a new era of growth and prosperity for Mexico, through the implementation of a series of structural reforms. The timeline for implementation of the proposed reforms extended to the second semester of 2018.

The purpose of this paper is to examine briefly whether there has been progress toward the Pact’s goals since it was signed; and whether any measures taken since then — including current economic policies — are likely to help Mexico break out of its long economic slump and forge a different path toward economic and social progress.

Conclusion

Five years into the Pact for Mexico, it is clear from the available data that the Pact’s promises to launch a new era of economic and social progress have not begun to materialize. But the problem seems to be much deeper than any administrative or political obstacle. Rather, it seems that the country’s persistent sluggish growth, poverty, and inequality are rooted in a set of important economic policy choices that have been made consistently for a long time. And as can be seen from the IMF Article IV Consultation and other public statements and actions by officials, the current political and economic authorities are committed to continue with this economic program.

After decades of poor economic performance that left Mexico in 18th place among 20 other Latin American countries in terms of income growth per person for the twenty-first century, the country faces serious downside risks in the years ahead. Most importantly, the US Federal Reserve is on track to raise short-term interest rates four times this year, with more increases in 2019. In the United States, all of the recessions in the post-WWII era were triggered by the Fed raising interest rates, with the exception of the last two, which were caused by the bursting of asset bubbles (in the stock market in 2000 and in the housing market in 2007).

Mexico’s dependence on the US economy for about 80 percent33 of its exports means that it is quite vulnerable to a US recession; but even without a US recession, the Fed’s interest rate hikes can have a severe impact on the Mexican economy if it draws away sufficient capital flows. This was seen in the 1994–95 peso crisis, where Mexico lost 9.5 percent of GDP in a downturn that was triggered by the Fed’s cycle of interest rate hikes at the time. And as noted above, the country’s hyperliberalization of financial markets also made it vulnerable to the Fed’s tapering of quantitative easing in 2013. These hyperliberal financial markets remain a source of vulnerability, and they make Mexico more vulnerable than it otherwise would be to turbulence in international financial markets that may already be beginning in this Fed tightening cycle.

Thus Mexico, under the current long-term policy regime described above, is committed to paying down the public debt when growth picks up even slightly; and when there are storm clouds on the horizon (which also include the turbulence of current relations with the United States and the uncertainty of NAFTA renegotiation), fiscal and monetary policy become even more of a drag on economic growth. Mexico is therefore caught in a trap of low investment and low growth, without making the necessary public investments in infrastructure, research and development, or education.

Without such investment, it cannot maintain its international competitiveness (even in US markets with respect to China), boost long-term productivity growth, or even maintain the necessary fiscal revenues from Pemex — not to mention reducing poverty or inequality. It seems clear that a new policy regime should be considered.

1 The only major party that isn't associated with the Pact is Morena, which was only formally created in 2014. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the 2018 presidential candidate for Morena, has criticized the Pact and advocated for a more developmentalist economic program, including some industrial policy and a somewhat expanded social safety net.

2 Weisbrot et al. (2017).

3 Average per capita GDP growth between 2000 and 2017. IMF (2018a).

4 The historical time series for poverty was discontinued by CONEVAL and values based on this methodology are only available until 2014, while calculations based on the new methodology only begin in 2012.

5 CONEVAL (2014), and Cordero and Campos, coords. (2016, p. 98).

6 Scott (2009, p. 25).

7 IMF (2013).

8 Notimex (2013).

33 Banco de México (2018f).

Spread the word