Black Bostonians in the 19th Century Thought the 14th Amendment Didn’t Do Enough to Protect Black Voting Rights

July 2018 is a challenging time to celebrate the 150th birthday of the Fourteenth Amendment. Despite decades of apparent progress, the provisions of the amendment continue to be under attack. A major battleground in the war for the Fourteenth Amendment is the full and equal participation of all citizens in American democracy. This year, the US Supreme Court addressed new challenges to voting rights and representation. Justice Sonya Sotomayor made clear the urgency of the topic in her recent dissent opposing state restrictions on voting, arguing that they have an unequal impact on racial minorities. “Our democracy,” the justice wrote, “rests on the ability of all individuals, regardless of race, income, or status, to exercise their right to vote.” Echoing generations of civil rights activists, Sotomayor affirmed the importance of unrestricted suffrage as the foundation of American democracy, calling it the “most precious right that is “preservative of all rights.” 150 years ago, as African Americans themselves sought to preserve their hard won freedom they looked to the Fourteenth Amendment as the protector of their “most precious right.”

Best known for its affirmation of birthright citizenship and due process, the Fourteenth Amendment is one of the cornerstones of modern American Civil Rights law. Yet its origins as a voting rights amendment are often overlooked. This important aspect was fundamental to how African Americans especially interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment on the eve of its birth 150 years ago and forges a deep connection between American citizenship and suffrage.

In these early debates members of Boston’s African American community were crucial voices seeking citizenship inseparable from universal and unabridged suffrage. During its ratification in the aftermath of the Civil War African Americans criticized the amendment as a conservative compromise prioritizing political expediency over the full-scale protection of black freedom, especially voting rights.Black critics feared that if given an opening, white opponents of black rights would surge back into power closing the door on a positive black future in America.

Section two of the amendment was of special concern to black opponents. This section limited voting in federal elections to males over the age of twenty-one, but penalized those states that denied or “in any way abridged” voting (except in the case of “participation in rebellion, or other crime”). In such cases the basis of its congressional and electoral representation would be reduced in portion of those disenfranchised. For critics of the amendment, this penalty was inadequate and represented a compromise that still allowed for prohibitions on voting. If states could choose between enfranchising African Americans or losing representation, black activists were sure they would pick the latter.

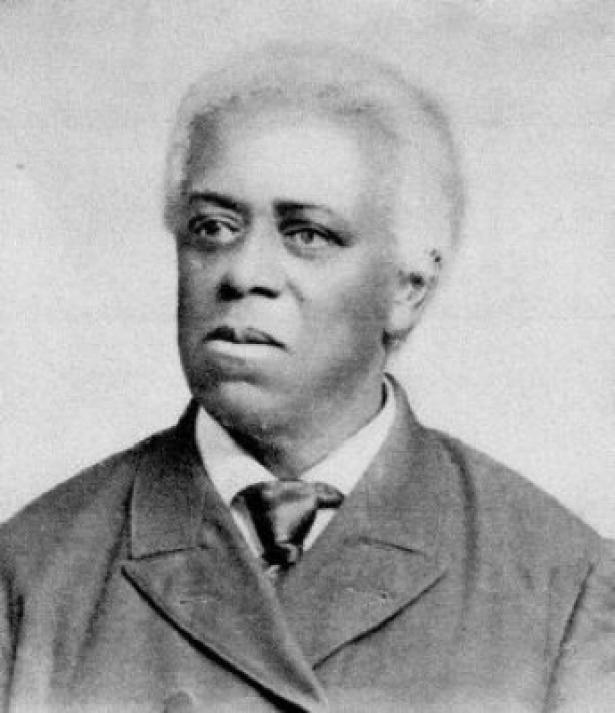

Black critiques of the Fourteenth Amendment were heard loudly in Massachusetts, which had a history of radical support for black rights. The election of black state representatives placed African Americans in a unique position in the state to weigh in directly on the ratification process. Their opposition slowed down the amendment’s ratification, making Massachusetts the last in the Northeast and one of the last in the North to ratify the amendment. Soon after the end of the war, former Civil War Lt. Charles Mitchell joined Edwin Garrison Walker, attorney and son of anti-slavery activist David Walker, as the first two African Americans elected to the Massachusetts legislature, giving both of them a prominent place from which to express the concerns of the amendment’s critics.

Edwin Walker, as a member of the Federal Relations Committee, was especially well positioned to offer his thoughts on the amendment. With his input the committee issued a powerful majority indictment of the legislation. The committee positioned its report as the only one in the nation directly including the voices of African Americans. Ratification without participation of African Americans, they argued, was a farce. “It is easy,” they wrote, “for white men, who practically wield the whole political power of the country, to regard with comparative indifference the rights of the long proscribed classes.” Walker, as part of the committee, made sure his voice was heard.

In the first speech by any African American on the floor of the Massachusetts House, Walker thundered: “The amendment carefully guards everything else but the interests of millions of blacks in this country.” Walker had no faith that without the explicit constitutional protection and enforcement of black voting, white politicians would move Reconstruction forward in ways that would benefit African Americans and secure their rights.

Despite their vigorous protest, the legislature eventually ratified the amendment and the US Congress approved it in July 1868. Both Mitchell and Walker, however, remained steadfast and voted against the amendment’s adoption. Even after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment prohibiting explicit racial disenfranchisement, Walker thought the protections were too narrow. As Walker and other opponents of the Fourteenth predicted and feared, states would go on to adopt, and the Supreme Court would allow, “race neutral” policies like poll taxes and literacy tests to restrict black suffrage within the bounds of the new amendment, a trend that continues today with the upholding of voter registration restrictions and gerrymandering despite opposition and protest from civil rights groups.

One hundred and fifty years after Black activists like Walker fought so ferociously for unrestricted voting rights, similar issues remain a driving force in civil rights struggles today. As NAACP Legal Defense Fund president and director-counsel Sherrilyn Ifill laments, “we’re here 150 years after the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment still fighting for the full ability of African Americans to vote and participate equally in the political process.” As 19th century activists showed, the courts or legislatures alone are often unreliable protectors and advocates of equality. They swore “earnest, and unceasing agitation,” declaring at a national convention, “no peace until the suffrage question was settled.” Unfortunately, the question remains unanswered still today and the call for agitation continues.

Millington W. Bergeson-Lockwood, a historian of race, law, and politics in the nineteenth century, is the author of Race Over Party: Black Politics and Partisanship in Late Nineteenth-Century Boston (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). You can follow him on Twitter here: @millingtonbl.

Spread the word