Mass organization, non-violent civil disobedience, and a little unlawful protest have been effective ways to draw attention to issues and change public policy. Today’s anti-gun violence, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter activists can learn lessons from both the success and failure of the 1917 food riots led by immigrant women that swept through United States cities.

In February 1917 the United States still had not entered the Great War in Europe. But the week of February 19-23, 1917, there was a wave of food riots in East Coast United States cities attributed to wartime food shortages, profiteering, and hoarding. The New York Times reported riots in New York City’s the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan and in Boston, Massachusetts, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

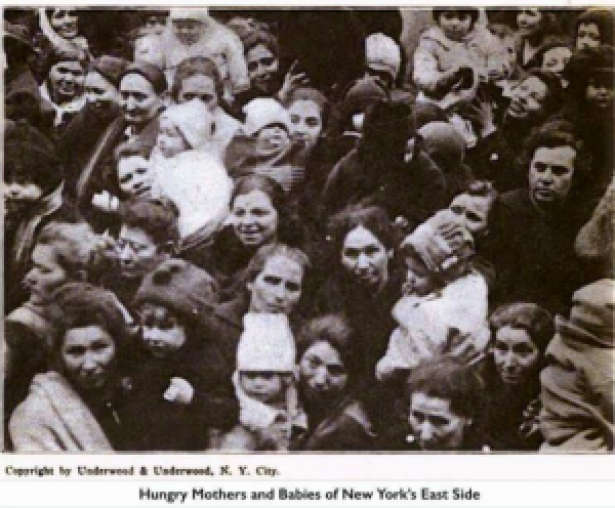

In Williamsburg and Brownsville, Brooklyn an estimated 3,000 women rioted overturning peddler’s pushcarts and setting them on fire after food prices spiked. On New York City’s Lower East Side an army of women, mostly Jewish, invaded a kosher poultry market and blocked sales the day before the Jewish Sabbath. They protested that the price of chicken had risen in one week from between 20 and 22 cents a pound to between 28 and 32 cents a pound. Pushcarts were overturned on Rivington Street and at a similar protest in the Clermont Park section of the Bronx. Four hundred of the Lower East Side mothers, many carrying babies, then marched on New York City Hall shouting in English and Yiddish, “We want food!” “Give us bread!” “Feed our children!” The Manhattan protests were organized by consumers committees led by the Socialist group Mothers’ Anti-High Price League, which had also organized a successful a boycott on onions and potatoes.

At the City Hall rally, Ida Harris, President of the Mother’s Vigilance Committee, declared: “We do not want to make trouble. We are good Americans and we simply want the Mayor to make the prices go down. If there is a law fixing prices, we want him to enforce it, and if there isn’t we appeal to him to get one. We are starving – our children are starving. But we don’t want any riot. We want to soften the hearts of the millionaires who are getting richer because of the high prices. We are not an organization. We haven’t got any politics. We are just mothers, and we want food for our children. Won’t you give us food?”

After the rally the police arrested Marie Ganz, known in leftwing circles as “Sweet Marie,” when Police Inspector John F. Dwyer claimed he heard her inciting a group of women to continue rioting while she was speaking in Yiddish, a language it is unlikely that Dwyer understood. Ganz was soon released with a suspended sentence. Dwyer, four years later, was implicated in a Congressional investigation of real estate fraud in New York City.

New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, who was away from City Hall during the protests, finally meet with the group’s leaders and then directed city commissioners of Charities, Health and Police to determine whether there were cases of starvation or of illness from insufficient nourishment amongst the city’s working class and poor.

At a public hearing the city’s Board of Estimate and Apportionment unanimously passed a resolution instructing its Corporation Counsel to draw up a bill to be presented to the State Legislature City that would authorize the city to purchase and sell food at cost during emergencies. It also urged Congress to fund an investigation of food shortages and price spikes. Speakers at the hearing in favor of immediate action to address food shortages and price hikes included Lillian D. Wald of the Henry Street Settlement, “Sweet Marie” Ganz, and Rabbi Stephen Wise of Manhattan’s Free Synagogue.

Ganz told the hearing, “We are all of a common people and we would lay down our lives for this country. The people are suffering and ask you to do what you can for them. What you should do is get after the people who have been cornering the food supply.

Rabbi Wise demanded to know if “there is food enough the city or there is not food enough. If there is not food enough here then the city officials should do what England and Germany have done. They should have supplies passed around equally. If there is enough food, the question is: What can be done to control prices?”

Speaking directly to Mayor Mitchel, Rabbi Wise declared: “If an earthquake should happen, you would not hesitate a moment, Mr. Mayor, to go to the Governor or to telephone to the President at Washington if a telephone could be used, or go to General Wood at Governors Island and demand army stores. Of course, that would be an emergency, but this is an emergency also, though, of course, it is not as spectacular an emergency as an earthquake would cause. But the fact remains that you have got to take energetic steps. Let us have an end of this cheap peanut politics.”

In response, the Mayor launched a campaign to have women substitute rice for potatoes while George W. Perkins, the chairman of the city’s Food Committee, personally donated $160,00 for the purchase of 4,000,000 pounds of rice and a carload of Columbia River smelts from the State of Washington. Arrangements were also made with William G. Willcox, President of the New York City Board of Education, to distribute a flyer to every school child encouraging parents to purchase and serve rice as a way of holding down the price of other commodities.

Following the food riots, Congressman Meyer London, a Socialist who represented a Manhattan district, gave an impassioned speech in Congress where he argued: “While Congress is spending millions for armies and navies it should devote a few hours to starving people in New York and elsewhere. You have bread riots, not in Vienna, nor in Berlin, not in Petrograd, but in New York, the richest city of the richest country in the most prosperous period in the history of that country.”

Abraham Cahan, editor of the Jewish Daily Forward, a Socialist and Yiddish language newspaper, reported that they had investigated a number of cases and that families, even with working members, were suffering from hunger.

After speakers at the Boston rally denounced the high cost of food, as many as 800 people, mostly women and children, looted a grocery and provision store in the West End. Police finally suppress the rioters. Philadelphia was under virtual marshal law after a food riot led to the shooting of one man, the trampling to death of an elderly woman, and the arrest of four men and two women. Several hundred women attacked pushcarts and invaded shops.

The United States Attorney for Massachusetts announced the formation of a special Federal Grand Jury to investigate food shortages and price increases. He blamed “local intrastate combinations” that were forcing up prices. New York County District Attorney Edward Swann also began an investigation into reports that potatoes were being warehoused on Long Island while farmers and agents waited for prices to rise.

Another possible source of the probably were coal shortages caused by wartime demand that were disrupting food supply lines. The Bangor & Aroostook Railroad in Maine, that served the country’s chief source for potatoes, reported it had only a five-day supply of coal in stock.

The Times also reported on the formation of “Feed America First” in St. Louis, Missouri. Police officials warned the protest movement might be the result of pro-German propaganda designed to pressure the Wilson administration to embargo food shipments to European combatants. Federal investigators, however, argued that there were no facts supporting this rumor.

Pressure from protestors and the city government pushed New York State Governor Charles S. Whitman to endorse emergency measures to contain food prices. In a public announcement he declared that “There is no doubt in my mind that the situation is the most serious perhaps in the history of this State, and it will grow worse before it grows better. I intend to take any steps that may be necessary to bring relief to the famine-stricken poor in New York City and other communities where there is widespread suffering.” Whitman then called for the immediate passage of the Food and Market bill proposed by a special state legislative committee headed by State Senator Charles W. Wicks. However, by mid-March the original Wicks Committee bill, which would have allocated broad power to the city government to regulate food markets, was dead after facing fierce opposition from farm groups in upstate regions.

A month later everything changed when the United States entered the war. The Socialist Party of America continued its opposition to United States involvement and many of its leaders were imprisoned while the mother’s food campaign receded from public view.

Jasmine Torres, a student in the Master of Arts program in Forensic Linguistics at Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY, co-authored this essay

Spread the word