The history of documentary film-making would look very different without DA Pennebaker, who has died aged 94. Though best known for his revelatory film Dont Look Back, about Bob Dylan’s 1965 UK tour, Pennebaker made bold and idiosyncratic films across a broad range of subject matter, from White House politics, showbusiness and the car-maker John DeLorean to global energy supplies and a competition among elite French pastry chefs. He was also a pioneer of portable cameras that could record sound synchronised with images, a technical leap that revolutionised documentary-making and inspired the “direct cinema” movement of the late 1950s.

Dont Look Back stands as one of the most memorable and influential films of its era, as both a musical and social document. “Dylan suddenly turned pop music upside down,” Pennebaker said. “He did it in a funny, naive way but he did it by making up a whole new kind of music. He was an existentialist model and nobody could figure out where to stick him.” In 2007 Pennebaker released 65 Revisited, which included full-length musical performances absent from the original Dont Look Back.

“It requires a certain amount of luck and you assume it will happen,” Pennebaker said of his approach to film-making. “It’s like playing blackjack in Vegas – you assume you’ll be lucky or you wouldn’t do it at all.” But Pennebaker’s “luck” was rooted in technical expertise and a gift for patient observation.

Donn Alan Pennebaker was born in Evanston, Illinois, the only child of John Paul Pennebaker, a commercial photographer, and his wife, Lucille (nee Levick). Soon after he was born his parents divorced, after which Donn lived in Chicago with his father. He went to Yale University, but his studies were interrupted by the second world war, during which he served as an engineer in the naval air corps.

He graduated from Yale in 1947 with a degree in mechanical engineering, and started Electronics Engineering, a company which exploited then-primitive computer science to create a pioneering airline reservation system. He sold the company, proposing to try his hand as a writer and painter, but a friendship with the film-maker Francis Thompson spurred him to make Daybreak Express (1953), a dynamic vision of New York shot from an elevated subway train, with a Duke Ellington soundtrack.

DA Pennebaker in his offices in New York City, 1995. Photograph: David Corio/Getty Images

In the late 1950s, Pennebaker formed the production company Drew Associates with the director Richard Leacock and the former Life magazine editor Robert Drew. The company made films for a variety of outlets, notably the ABC News series Close-up and Time-Life Broadcasting’s Living Camera. Their first major effort was Primary (1960), for which Pennebaker and his partners filmed five days of campaigning for the 1960 Democratic presidential primary which led to the nomination of John F Kennedy. Pennebaker had developed a portable 16mm camera with synchronised sound recorded on a Nagra tape recorder, using a Bulova clock movement to guarantee accuracy. Previously, sound would be separately recorded and added to the film later.

“There was nobody else working on a camera that you could haul around with you outside and get sync dialogue,” Pennebaker said. “At the time, the kind of documentary films being made were all covered with hymn-like music and everything was virtuous. The idea was to use the documentary concept as evidence of how well your government was treating you.”

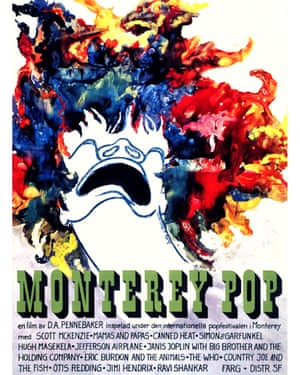

Poster for DA Pennebaker’s 1967 documentary Monterey Pop, about the California music festival. Photograph: John D Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images

Primary was hailed for its revolutionary techniques, but as Pennebaker pointed out, TV networks were suspicious of this new form of film-making. “It denied editorial control, because if you sent a person out with a camera you couldn’t tell him what to do,” he said. “TV wanted people running cameras in the studio and management was in the room selecting the shot. Control was part of the process that this sort of film-making was denying.”

Further work for Drew Associates included Crisis, about Robert Kennedy’s confrontation with Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace, and Jane, a profile of the young Jane Fonda, but in 1963 Pennebaker and Leacock left to form Leacock Pennebaker Inc. The move seemingly had a liberating effect on Pennebaker, and he was soon at work on Dont Look Back (having been invited to join the UK tour by Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman, as long as he paid his own way). It was shot in 1965 and released in 1967.

In that year, too, Pennebaker made Monterey Pop, another memorable artefact of the period capturing the eponymous California pop festival, which featured the Who, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. He then worked as cinematographer on Norman Mailer’s films Wild 90, Beyond the Law and Maidstone. A collaboration between Leacock, Pennebaker and the French director Jean-Luc Godard failed to fulfil its original aspirations – Godard envisaged a document of American social upheaval in the shadow of the Vietnam war – but Pennebaker eventually released his own version of it called 1 PM (1971).

Norman Mailer and Germaine Greer debating in the 1979 documentary Town Bloody Hall, by DA Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus. Photograph: UCLA Film & TV Archive

He made another celebrated pop music film with Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1973), documenting David Bowie’s final Ziggy Stardust concert, at the Hammersmith Odeon in London.

Pennebaker had been married twice (both marriages ended in divorce) before he met Chris Hegedus, who joined his film company in 1976. By the time they married in 1982 they had already collaborated on a string of significant documentaries. The Energy War (1978) was a three-part “political soap opera” for PBS television, chronicling President Jimmy Carter’s 1977 battle to pass a bill deregulating natural gas. Town Bloody Hall, in which Mailer debated fiercely with a group of radical feminists including Germaine Greer and Diana Trilling, had been filmed by Pennebaker in 1971, but he had considered the footage unusable. Hegedus disagreed, and made a new edit for a 1979 release.

DeLorean (1981) gave a unique insight into the controversial sports car entrepreneur who set up a factory in Northern Ireland, while the pair delivered their most impressive political film with The War Room (1993), which probed behind the scenes during Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. It won riotous acclaim from critics, and brought a terse “Good movie – Bill” from Clinton. It later provided inspiration for George Clooneyand Steven Soderbergh’s 2003 political TV series for HBO, K Street.

Don Pennebaker and his wife Chris Hegedus, with whom he collaboratored on a string of documentaries, photographed in 2003 while promoting Down From the Mountain. Photograph: Graham Turner/The Guardian

Pennebaker got back on the rock’n’roll tour bus for 101 (1989), a film about Depeche Mode, which focused on the 101st date of the band’s world tour at the Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena. However, in contrast to Pennebaker’s earlier nimble hit-and-run style, this was a consciously grandiose effort. He had had difficulty getting Monterey Pop shown on TV and did not want a repeat performance. “We didn’t even want to use the word ‘documentary’, we wanted to make a big film,” he confessed. “If it was perceived as a big film, then TV would buy it. So with 101, instead of a little gas station, we were making a gigantic Taj Mahal.”

Music and showbusiness continued to exert an attraction. Branford Marsalis: The Music Tells You (1992) was a portrait of the jazz saxophonist, while Down from the Mountain (2000) was a documentary and concert film about the country musicians who recorded the soundtrack for the Coen Brothers’ movie O Brother, Where Art Thou?

In 1970 Pennebaker had made Original Cast Album: Company, about the soundtrack recording of Stephen Sondheim’s Broadway musical, and in 2004 he delivered Elaine Stritch: At Liberty, a documentary record of the Company star’s one-woman show.

Kings of Pastry (2010) was Hegedus/Pennebaker’s account of 16 French pastry chefs competing for the coveted Meilleur Ouvrier de France award in Lyon. In 2016 came Unlocking the Cage, a documentary about attempts to secure legal rights for animals.

Whatever the subject matter, Pennebaker never lost his faith in the power of the documentary medium. “Ideas are probably the most powerful weapons around, and the documentary film is a fantastic way to express an idea,” he said. “It can take hold and spread so fast and I think it can’t be controlled the way movies can be controlled, by how much money you spend on advertising and what theatres you put it in.”

In 2012, Pennebaker received an honorary Oscar for his lifetime body of work.

He is survived by Hegedus, their son, Kit, and daughter, Jane; his daughters, Stacey and Linley, and son, Frazer, from his first marriage, to Sylvia Bell; and son, Jojo, and daughters, Chelsea and Zoe, from his second marriage, to Kate Taylor.

• Donn Alan Pennebaker, film-maker, born 15 July 1925; died 1 August 2019

Spread the word