If recent reports hold true, the Washington NFL team name is finally on its way out. Despite a lot of grand declarations about tradition, legacy, and tribute, it seems that the winds have shifted enough to make the rich people in charge of such decisions a little less eager to be attached to a slur franchise: Three owners, with a combined 40 percent stake in the team, have said they intend to sell if the R-word remains. Nike, Amazon, and Walmart took a stand at the last possible second, pulling their Washington merchandise. Even head coach Ron Rivera told The Washington Post that the team must find a new name, with the paper reporting that his preference is for something that is “respectful of Native American culture and traditions and also is a tribute to the military.”

It’s uncertain what will happen next, but it would be a mistake to treat whatever it is—a new name, a new logo, some pat apologies from the people who fought to maintain the slur for so long—as the end of the issue. The Washington franchise was the most public facing and egregious example of the problem, but more than just a set of derogatory or reductive names and symbols, the phenomenon has always been in service of maintaining a fantasy version of history and a practice of tokenizing or mythologizing Native people and communities. As put to me by Bryan Brayboy, a Lumbee citizen and the President’s Professor of Indigenous education and justice at Arizona State University, “It’s a myth that has become a truth, one that gets re-instantiated with each telling, and the telling is frequent—the telling that we don’t exist anymore.”

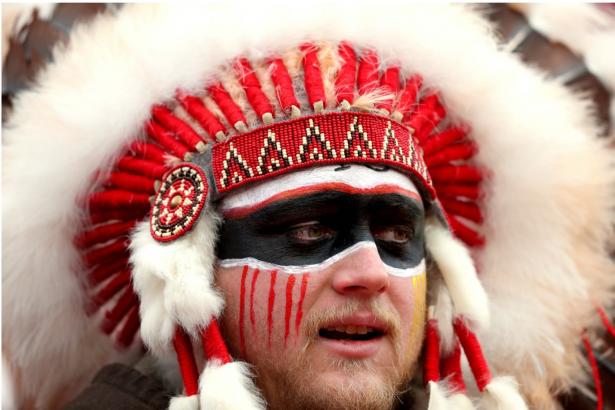

The goal in this fight is not only to do away with racist caricatures like Chief Wahoo and slurs like the R-word, though they should have already been scorched a century ago. But these symbols are only the latest weapons wielded against Native peoples. Their continued presence seeks to lock us in the past, even in a moment where we are standing fully in the spotlight, reminding this nation that despite its sustained efforts to marginalize and erase our communities, we are still here and have many voices. Combatting this systemic diminishment starts with acknowledging that America’s history of physical violence, malicious stereotypes, invisibility in the media and American curricula, and caricatures in both professional sports franchises and local high schools are not separate matters. They all feed the same monster of colonization.

“The power of erasure is profound. Originally, it was about de-territorialization and the erasure was the physical erasure of people,” Brayboy said, referencing the practice of scalping by Europeans that the R-word refers to and the wider history of violent colonization. “But it has become rhetorical and discursive at this point,” he continued. “Erasure now happens by suggesting that two percent of the country’s population doesn’t exist. And that’s a pretty profound movement. It doesn’t mean it’s not violent. It just means it’s not physically violent.”

Try and apply this line of argument to an ardent defender of one of these racist mascots, though, and the response will likely be the same one issued for years: The team names are meant to honor Native people, not denigrate them. The mindset that undergirds this kind of thinking is best seen on the local level, away from the politicized discourse that surrounds the Washington NFL team. This myth—that Native people offered their land willingly and faded away peacefully and now need white people to remember us in this specific fashion—is coiled around the DNA of hundreds of communities. A single mascot is effectively the only connection many Americans have to the hundreds of Native communities and cultures that are still thriving, still governing, still producing art, still participating in civic life, still navigating the same systemic foreclosures and barriers that have long existed. Without these pan-Indian shields of ‘honor’, the truth of a stolen land—raw and ugly—would barrel into them.

So once we have seen the end of Native mascots, a horizon we may finally be approaching, the country will still be left with the erasure, tokenization, and colonization that it was built on—these founding myths and recurring violences. In order to reconcile those wrongs, Native voices, and the desires of Native communities, must lead the way forward.

“We’ve been trying to, in a very concrete way, say it’s not okay for anyone to take unilateral action affecting our land, territories, resources, and people,” Fawn Sharp, president of the National Congress of American Indians, told me, pointing to the Dakota Access pipeline as a prime example of what happens when tribal nations are ignored. “If we can concretely demonstrate how we can turn those who degrade, exploit for profit, and inflict harm on Native people into allies, and how, through that relationship, truth can be told and people can be educated,” Sharp continued, “then we can walk a collective path of reconciliation and understanding that can be a very powerful in my mind.”

The end of Native mascots is one piece of righting this historic wrong, but it also has immediate material impacts that shouldn’t be overlooked: These mascots are actively harmful to both Native and non-Native youth. Last month, before the R-word was even on the chopping block, Indian Country Today reported on a recent study published in the journal Race Ethnicity and Education that thoroughly reviewed other studies about the effects of Native mascots on children. The researchers concluded that, “Regardless of the stated intent of those who support Native mascots (i.e., to `honor’ Native Americans) and regardless of opinions about them, these mascots induce or correlate with negative psychosocial outcomes.”

“I talked to the leaders at the Lummi Nation last year, because there was a young kid who was kicked on the basketball court and the ref kind of high-fived the guy,” Sharp said. “At the same time, a young Native girl was forced to cut her braids by one of her teachers in New Mexico. And then that same weekend, as I heard all these things happening, Chief Hoskin at the Cherokee Nation announced they were going to withdraw their charitable contributions to the local schools until they addressed institutional racism in the schools.”

Sharp, who told me that she experienced similar forms of discrimination growing up as a child in the Quinault Nation, saw these three concurrent examples as sign of just how deep this mentality has been embedded not just in athletics, but in the Native childhood experience. “It’s unthinkable that every single day, when our kids are in schools, they’re facing that level of hurt,” she said.

In a recent article for The Wall Street Journal, reporter Andrew Beaton put a magnifying glass over the case of Anderson High School in Ohio, which uses the R-word as its mascot. “If the name is changed, it will destroy the community,” an Anderson alumni said in a video posted to a website dedicated to keeping the slur. Last summer, the Idaho Statesman reviewed the case of Teton High School, which finally changed its name after nearly a decade of debate. “We wanted to be as brave, as fearless and as strong as they were,” wrote one name defender. “We are keeping the memories of those who were here actually alive.” (On the topic of alive Natives, at a two-hour school board meeting, numerous Shoshone-Bannock citizens, including the tribal nation’s vice chairman, explained to the community why they took offense to the name.)

“We have to have a larger conversation about the connection between these mascots and these iconography and things like monuments,” Brayboy said. “How do we begin to think about people’s connections and ties to these things—so much so that it becomes so emotional for them, that they enter into a range the thought of taking it away from them? These things are not alive. They are not our relations. They serve no purpose except for instantiating often, some false narrative—a myth that has become truth. We have to reckon with some of that.”

The active harm caused by these mascots, though, gets lost when the discussion about the issue is being chiefly viewed through the lens of the Washington NFL team. The conversation immediately becomes narrowed and flattened—Trump’s decision to waddle into the debate all but solidifies the limitations of the conversation’s usefulness. Defending the R-word becomes less about reason and compassion and more about not being “too PC.” So look beyond Washington. Look anywhere. When you remove the politics of the fight around the Washington NFL team and look at how these mascot debates play out on a local level, where money is mostly removed from the equation, it becomes clearer why it is such a trying task to get people to understand that all Native mascots, not just the particularly heinous ones, are harmful. And why, long after the mascots are gone, there will be more work to do to reconcile why they lasted as long as they did.For the most part, the people who show up these kinds of school board meetings are not extremists. They’re not on the fringe of society. They are regular, working people who remained in their hometowns and have been subjected to an incorrect education of who Native people are, in a present tense. They maybe hold conservative political views and consume a bit too much Facebook or cable news, as many normal people do, and so rather than take the opportunity to engage with any tribal communities, they follow lock-in-step with the right’s desire to declare all critiques against their version of institutional racism as cancel culture run amok. (This emboldened mentality is not helped by the fact that these local fights to keep the names are often supported the likes of the Native American Guardian Association, which is paid by school boards to come to board meetings like these across the country to lobby in favor of the names, arguing that erasing the name will wholly erase Native people from the national consciousness.)

I’ve written posts like this in the past about the NFL franchise Kansas City Chiefs and Major League Baseball’s Atlanta Braves and Cleveland Indians. I’ve blogged about why it’s harmful for high school athletes to wear pan-Indian regalia, call themselves a “tribal family,” and put on a fake war dances. At a certain point, even if it’s a veritable fact that Native mascots are on the decline, it feels like screaming into a void, where the only people actually taking the time to listen to the arguments being laid out are the people screaming alongside me. Julian Brave Noisecat addressed this point poignantly in a recent essay for The Undefeated: On a personal level, being forced to spend your time constantly explaining in detail why these mascots are demeaning and belittling to the same people who don’t even think you exist feels like the wrong fight to be picking. As Noisecat wrote, “It feels basic and tiresome. And no one wants to be basic or tiresome.”

But at a certain point, the basic and tiresome work becomes the important work. It may not be the most important work, but when I think about myself in ten years, when I think about any future children I might have, I know for a fact that I want that future to be one where our people are not marginalized and capitalized on by billionaires and underfunded schools alike. I don’t want my kid to look up at a stranger’s hat with a grinning Chief Wahoo and feel that familiar lump in their throat, or have to ask me why all these people are shouting a slur, or why their high school mascot is a deformed version of their ancestors.

“I have an 18 year old who is about to go off to college,” Brayboy said. “And he’s on social media and I see him engaged in conversation with people about this. And it was a remarkable thing for me to watch how he managed the conversation as people tried to pull him into these places—demanding proof of his ancestry and him saying, ‘I am who I am, and I don’t have to prove anything to you.’” just mine, but others who are figuring out ways to respond to this, which is one of the things that gives me some hope,” he continued. “It also fills me with a profound sense of sadness that my child has to be doing this.”

It does feel like we’re reaching a tipping point on the subject, but a world without Native mascots will not be a perfect world for Indian Country. The same strikes against sovereignty and citizenship and our place on this land will remain. So too will the work of unwinding the lingering effects of a century of being tokenized and caricatured. Native communities are very clearly up to the task of doing this work. The question is whether the American people are willing to embrace their past to forge a more just future. And if the only time that they think about us is when they see these symbols, then let them forget us again. It would be better to be forgotten than to be misremembered like this.

Nick Martin is a staff writer at The New Republic. Nick Martin @nicka_martin

Support creative journalism. Get a trial subscription to TNR.

Spread the word