The search for life in our solar system got a lot more exciting this week. On Monday, a team of scientists announced its members had detected phosphine gas in the caustic, hot atmosphere of Venus. So what? The gas — which you’d recognize by its fishy odor — is thought to be a byproduct of life.

“We did exhaustively search through all known chemistry ... and we didn’t find anything that could produce more than the tiniest amount of phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere,” says MIT planetary scientist Sara Seager, who was one of the co-authors on the discovery published in Nature Astronomy, says. That leaves us two possibilities: The gas was created by life or by some chemical interaction scientists don’t yet know about.

Seager is one of the leading dreamers and thinkers in astronomy, looking for life beyond our planet. She studies planets orbiting stars many light-years away and thinks about how to detect life on them and others closer to home, like Venus.

She’s also thinking creatively about the microscopic life forms that could potentially survive there. This summer, before the phosphine announcement, she and her co-authors published a speculative, hypothetical sketch of what life on Venus could look like. The vision is beautiful: a living rain of microbes floating, cyclically, in the clouds, blooming and desiccating continually for millions of years.

I wanted to hear more about this vision of life in a world so very different from our own, so I called her up.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Evidence for life on the planet next door

Brian Resnick

To start off: What’s the gist of the discovery that you and the team announced this week?

Sara Seager

We aren’t claiming we found signs of life. We are claiming we have a robust detection of the gas phosphine in the atmosphere.

[After searching] all the known chemistry — volcanoes, photochemistry, lightning — we didn’t find anything that could produce more than the tiniest amount of phosphine in Venus’s atmosphere. So we’re left with two possibilities. One is that there is some kind of unknown chemistry, which seems unlikely. And the other possibility is that there’s some kind of life, which seems even more unlikely. So that’s where we’re at. It took a long time to accept it.

Brian Resnick

Okay, so it’s very unlikely. Has Venus historically been thought of as a place life might exist in the solar system?

Sara Seager

It’s been fringe pretty much the whole time that it’s been a topic. Carl Sagan first proposed there could be life in clouds. There is a small group [of scientists] that writes about this topic. A lot of people love it. It’s like a closeted love because a lot of people are enthusiastic about it, but they either didn’t want to say so or they never had a reason to say so.

Brian Resnick

What do they love about it?

Sara Seager

I think it’s just the intrigue that there could be life so close to home.

[Venus is closer to Earth than Mars. It’s also the second-brightest object in our night sky, other than the moon.]

Why life would have to exist in Venus’s clouds, not on the surface

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21893647/venus_volcanoes_home.jpg)

An artist’s concept of active volcanoes on Venus.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Peter Rubin

Brian Resnick

As I understand it, if life exists on Venus, it wouldn’t be on the surface of the planet, but in its sulfuric acid clouds?

Sara Seager

It’s always been the theory because the surface is too hot for complex molecules.

Brian Resnick

What is too hot? What happens there?

Sara Seager

Molecules break apart. If you took a protein or an amino acid, or anything, and put it in high temperature, it would come apart into smaller fragments and atoms.

Brian Resnick

Why, then, is the atmosphere a better place to look for life?

Sara Seager

It has the things that astrobiologists think life needs. It needs a liquid of some kind. And there is liquid in the atmosphere, although it is liquid sulfuric acid.

Life needs an energy source. So there’s definitely the sun, at least as an energy source. Life needs the right temperature. In the atmosphere, there is the right temperature. And life needs a changing environment to promote Darwinian evolution. So if you want to break it down like that, that’s why. To simplify, it’s mostly the temperature argument. Temperature and liquid.

Brian Resnick

Do we know of any life form on Earth that can exist in liquid sulfuric acid?

Sara Seager

No, we don’t.

Brian Resnick

What makes it seem possible for life to exist in sulfuric acid?

Sara Seager

We simply don’t know. I think your questions are the next decades of research, basically.

Brian Resnick

How do you even begin to imagine life in such a different world — life that has to live in conditions that would be deadly for any life on Earth?

Sara Seager

It has to be made up of different building blocks than our life is made up of. Our building blocks — like proteins, and amino acids, and DNA — wouldn’t survive in sulfuric acid. Or life has to have found a way to have a protective shell, made of materials that are resistant to sulfuric acid.

The dance of (potential) life on Venus

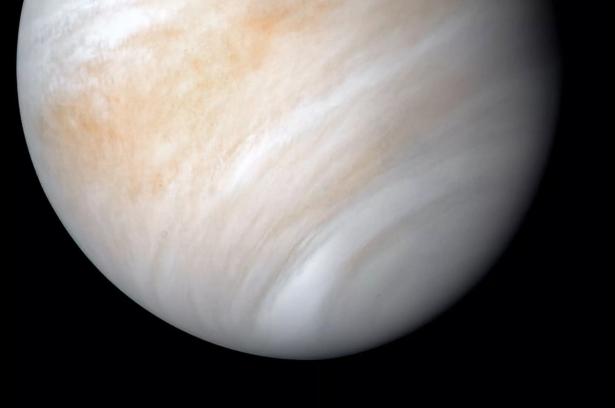

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21893652/venus20191211_16.jpg)

The surface of Venus, stitched together in a composite image.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Brian Resnick

Over the summer, you and your colleagues published a paper speculating on what life on Venus could look like. You describe that it could basically dance in the atmosphere, alternating between an active phase up high and a dormant phase down low. I found it to be kind of beautiful. Can you describe how you came up with this?

Sara Seager

I had to help plug a hole in the concept of life in the atmosphere. That’s where it came from. Life has to live inside the liquid droplets, to be protected from the outside.

But in these droplets — where life is living, reproducing, metabolizing — the droplets would collide and grow.

Over time, like four months or a year or so, the droplets get big enough, so they start settling out of the atmosphere, like rain, but really slowly.

And so my colleagues told me I had to figure out how life could survive. If it all just rains out, it couldn’t stay in the atmosphere for billions of years, or hundreds of millions of years.

Brian Resnick

How did you solve this?

Sara Seager

So I came up with this life cycle idea: as the droplets fall, they evaporate, and we’re left with a dried, spore-like life form. Now that’s not very massive; it stops falling and becomes suspended in a haze layer [lower down in the atmosphere]. And this haze layer is known to exist beneath the clouds of Venus. It’s very stable and long-lived. So the concept is that this haze layer is populated by dried-out spores, which can stay there for days, weeks, months years — and eventually they get updrafted back up to the region that has the right temperature for life, where it can attract liquid, hydrate it, and start their life cycle again.

Brian Resnick

It’s like a living rain, of sorts.

Sara Seager

Right.

Brian Resnick

Why wouldn’t the spore die suspended in that lower layer?

Sara Seager

It’s pretty warm there, so some might die. And this is all just a hypothesis, so it’s not a proven theory or anything, but for this to work, some of them have to live. We have examples on Earth of dried-out spore living a long time.

What it would mean to discover life on Venus

Brian Resnick

Why is it important to do this type of exercise, to be so speculative, and imagine life in a world so seemingly hostile to life?

Sara Seager

If we think about it and couldn’t find any possible way for life to be in the atmosphere indefinitely, that would be bad news for the enthusiasts for life on Venus. Does that make sense?

Brian Resnick

Yeah, if you can’t think of any hypothetical that allows life to survive, it’s hard to make a case to go look for it. Does the life you imagined fit in with in the new discovery of the phosphine gas?

Sara Seager

Yes. Well, it was motivated by the phosphine work.

Brian Resnick

What would it mean to find life on Venus?

Sara Seager

I think it would mean that if there’s life there, it has to be so different from Earth, and that we could show that it had a unique origin. It would just give us confidence that life can originate almost anywhere. And that would mean that our galaxy would be teeming with life. All the planets around other stars. It just sort of ups our thinking that there could be life everywhere.

Brian Resnick

Are you talking about a second genesis of life happening separately on Venus? Or would we have to figure out if there’s a common origin of life in our solar system? That something seeded life on both Earth and Venus?

Sara Seager

We’d have to figure it out.

How to find life on Venus, once and for all

Brian Resnick

What are the next steps, ideally?

Sara Seager

Our ideal next step would be to send a spacecraft or spacecrafts, plural, to Venus, that could involve a probe going into the atmosphere and measuring gases confirming phosphine, looking for other gases, looking for complex molecules that might indicate life, and maybe even searching for life itself.

Brian Resnick

Anyone working on that?

Sara Seager

Rocket Lab had mentioned about a month ago that they were planning to send a rocket to Venus. There are two NASA discovery class missions under a phase A competition [meaning they’re just mission proposals and need to be greenlit]. if they get selected for launch, they will get to go. Russia and India are planning to send something there. And I’ve started to lead a privately funded study. It’s not a mission. It’s just a study of what it would really take.

Brian Resnick

Can we answer this question — is there life on Venus — in our lifetimes?

Sara Seager

I think it is answerable in a human lifetime.

Brian Resnick

Is too much time and money spent on finding life on Mars? Venus seems to be neglected in terms of big NASA missions.

Sara Seager

Well, we don’t have infinite resources, unfortunately, but it sure would be nice to see more spent on Venus. We haven’t explored Venus for a very long time. You’d have to look up when the last time the US went to Venus. [It was the Magellan mission that launched in 1989.]

Brian Resnick

What would you love the public to think about and dwell on with this topic?

Sara Seager

Our solar system, our galaxy, our universe is full of mysteries. We’d like to solve them, but some end up being unsolvable and they just leave us in limbo. So hopefully that’s not going to be the case here.

Brian Resnick is a science reporter at Vox.com, covering social and behavioral sciences, space, medicine, the environment, and anything that makes you think "whoa that's cool." Before Vox, he was a staff correspondent at National Journal where he wrote two cover stories for the (now defunct) weekly print magazine, and reported on breaking news and politics.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Spread the word