Our unemployment insurance system has failed the country at a moment of great need. With tens of millions of workers struggling just to pay rent and buy food, Congress was forced to pass two emergency spending bills, providing one-time stimulus payments, special weekly unemployment insurance payments, and temporary unemployment benefits to those not covered by the system. And, because of their limited short-term nature, President Biden must now advocate for a third.

The system’s shortcomings have been obvious for some time, but little effort has been made to improve it. In fact, those shortcomings were baked into the system at the beginning, as President Roosevelt wanted, not by accident. While we must continue to organize to ensure working people are able to survive the pandemic, we must also start the long process of building popular support for a radical transformation of our unemployment insurance system. The history of struggle that produced our current system offers some useful lessons.

Performance

Our unemployment insurance system was designed during the Great Depression. It was supposed to shield workers and their families from the punishing costs of unemployment, thereby also helping to promote both political and economic stability. Unfortunately, as Eduardo Porter and Karl Russell reveal in a New York Times article, that system has largely failed working people.

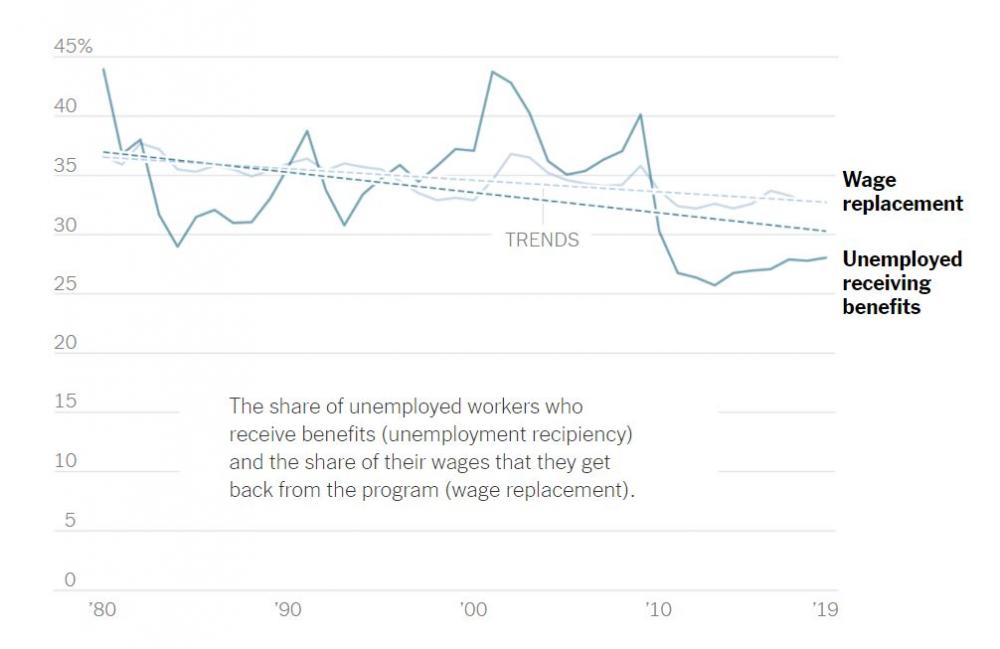

The chart below shows the downward trend in the share of unemployed workers receiving benefits and the replacement value of those benefits. Benefits now replace less than one-third of prior wages, some eight percentage points below the level in the 1940s. Benefits aside, it is hard to celebrate a system that covers fewer than 30 percent of those struggling with unemployment.

A faulty system

Although every state has an unemployment insurance system, they all operate independently. There is no national system. Each state separately generates the funds it needs to provide unemployment benefits and is largely free, subject to some basic federal standards, to set the conditions under which an unemployed worker becomes eligible to receive benefits, the waiting period before benefits will be paid, the length of time benefits will be paid, the benefit amount, and requirements to continue receiving benefits.

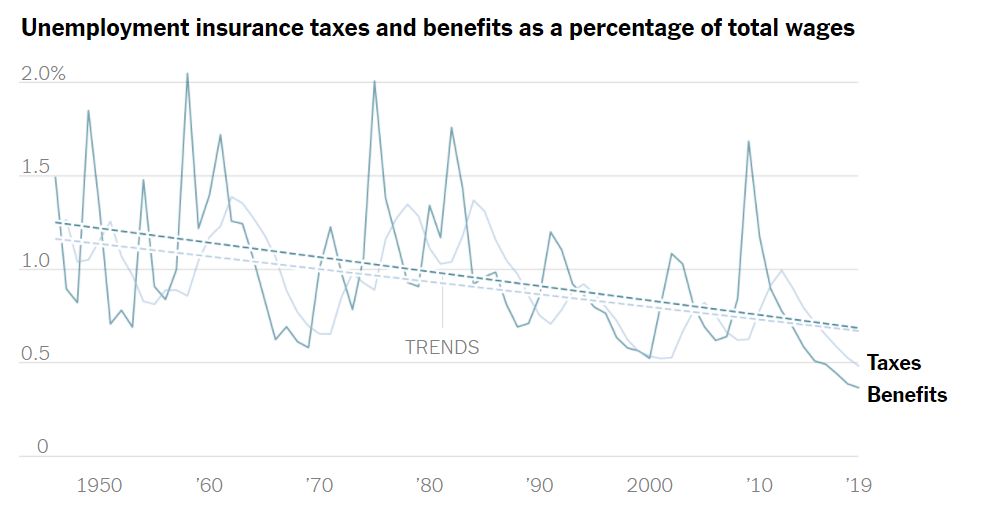

Payroll taxes paid by firms generate the funds used to pay unemployment insurance benefits. The size of the taxes to be paid depends on the value of employee earnings that is made taxable (the base wage) and the tax rate. States are free to set the base wage as they want, subject to a federally mandated floor of $7000 established in the 1970s. States are also free to set the tax rate as they want. Not surprisingly, in the interest of supporting business profitability, states have generally sought to keep both the base wage and tax rate low. For example, Florida, Tennessee and Arizona continue to set their base wage at the federal minimum value. And, as the figure below shows, insurance tax rates have been trending down for some time.

While such a policy might help business, lowering the tax rate means that states have less money in their trust funds to pay unemployment benefits. Thus, when times are hard, and unemployment claims rise, many states find themselves hard pressed to meet their required obligations. In fact, as Porter and Russell explain:

Washington has been repeatedly called on to provide additional relief, including emergency patches to unemployment insurance after the Great Recession hit in 2008. Indeed, it has intervened in response to every recession since the 1950s.

This is far from a desirable outcome for those states forced to borrow, since the money has to be paid back with interest by imposing higher future payroll taxes on employers. Thus, growing numbers of states have sought to minimize the likelihood of this happening, or at least the amount to be borrowed, by raising eligibility standards, reducing benefits, and shortening time of coverage, all of which they hope will reduce the number of people drawing unemployment benefits as well as the amount and length of time they will receive them.

Porter and Russell highlight some of the consequences of this strategy:

In Arizona, nearly 70 percent of unemployment insurance applications are denied. Only 15 percent of the unemployed get anything from the state. Many don’t even apply. Tennessee rejects nearly six in 10 applications.

In Florida, only one in 10 unemployed workers gets any benefits. The state is notably stingy: no more than $275 a week, roughly a third of the maximum benefit in Washington State. And benefits run out quickly, after as little as 12 weeks, depending on the state’s overall unemployment rate.

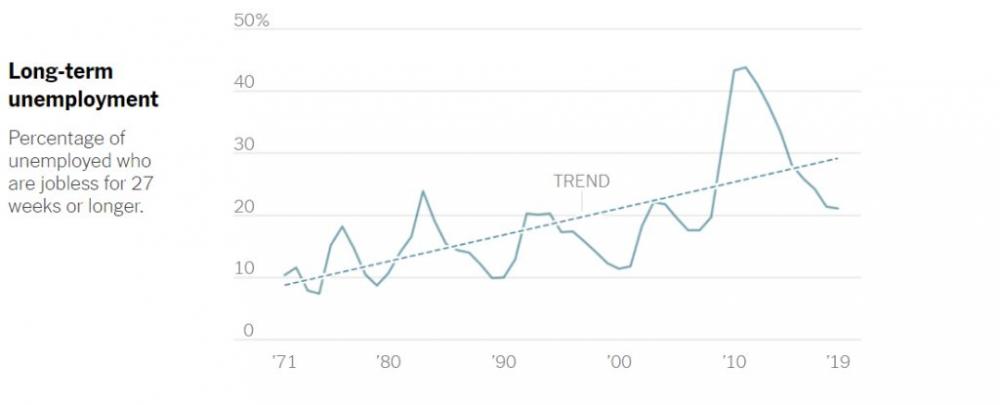

And, the growing stagnation of the US economy, which has led to more precarity of employment, only makes this strategy ever more fiscally “intelligent.” For example, as the following figure shows, a growing percentage of the unemployed are remaining jobless for a longer time. Such a trend, absent state actions to restrict access to benefits, would mean financial trouble for state officials.

Adding to the system’s structural shortcomings is that fact that growing numbers of workers, for example the many workers who have been reclassified as independent contractors, are not covered by it. In addition, since eligibility for benefits requires satisfying a minimum earnings and hours of work requirement over a base year, the growth in irregular low wage work means that many of those in most need of the system’s financial support during periods of unemployment find themselves declared ineligible for benefits.

By design, not by mistake

Our current unemployment insurance system and its patchwork set of state standards and benefits dates back to the depression. While President Roosevelt gets credit for establishing our unemployment insurance system as part of the New Deal, the fact is he deliberately sidelined a far stronger program that, if it had been approved, would have put working people today in a far more secure position.

The Communist Party (CP) began pushing an unemployment and social insurance bill in the summer of 1930 and, along with the numerous Unemployed Councils that existed in cities throughout the country, worked hard to promote it over the following years. On March 4, 1933, the day of Roosevelt’s inauguration, they organized demonstrations stressing the need for action on unemployment insurance.

Undeterred by Roosevelt’s lack of action, the CP-authored “Workers Unemployment and Social Insurance Bill” was introduced in Congress in February 1934 by Representative Ernest Lundeen of the Farmer-Labor Party. In broad brush, the bill mandated the payment of unemployment insurance to all unemployed workers and farmers equal to average local full-time wages, with a guaranteed minimum of $10 per week plus $3 for each dependent. Those forced into part-time employment would receive the difference between their earnings and the average local full-time wage. The bill also created a social insurance program that would provide payments to the sick and elderly, and maternity benefits to be paid eight weeks before and eight weeks after birth. All these benefits were to be financed by unappropriated funds in the Treasury and taxes on inheritances, gifts, and individual and corporate incomes above $5,000 a year.

The bill enjoyed strong support among workers—employed and unemployed—and it was soon endorsed by 5 international unions, 35 central labor bodies, and more than 3000 local unions. Rank and file worker committees also formed across the country to pressure members of Congress to pass it.

When Congress refused to act on the bill, Lundeen reintroduced it in January 1935. Because of public pressure, the bill became the first social insurance plan to be recommended by a congressional committee, in this case the House Labor Committee. However, it was soon voted down in the full House of Representatives, 204 to 52.

Roosevelt strongly opposed the Lundeen bill and it was to provide a counter that he pushed to create an alternative, one that offered benefits far short of what the Workers Unemployment and Social Insurance Bill offered, and was strongly opposed by many workers and all organizations of the unemployed. Roosevelt appointed a Committee on Economic Security in July 1934 with the charge to develop a social security bill that he could present to Congress in January 1935 that would include provisions for both unemployment insurance and old-age security. An administration approved bill was introduced right on schedule in January and Roosevelt called for quick congressional action.

Roosevelt’s bill was revised in April by a House committee and given a new name, “The Social Security Act.” After additional revisions the Social Security Act was signed into law on August 14, 1935. The Social Security Act was a complex piece of legislation. It included what we now call Social Security, a federal old-age benefit program; a program of unemployment insurance administered by the states; and a program of federal grants to states to fund benefits for the needy elderly and aid to dependent children.

The unemployment system established by the Social Security Act was structured in ways unfavorable to workers (as was the federal old-age benefit program). Rather than a progressively funded, comprehensive national system of unemployment insurance that paid benefits commensurate with worker wages, the act established a federal-state cooperative system that gave states wide latitude in determining standards.

More specifically, the act levied a uniform national pay-roll tax of 1 percent in 1936, 2 percent in 1937, and 3 percent in 1938, on covered employers, defined as those employers with eight or more employees for at least twenty weeks, not including government employers and employers in agriculture. Only workers employed by a covered employer could receive benefits.

The act left it to the states to decide whether to enact their own plans, and if so, to determine eligibility conditions, the waiting period to receive benefits, benefit amounts, minimum and maximum benefit levels, duration of benefits, disqualifications, and other administrative matters. It was not until 1937 that programs were established in every state as well as the then-territories of Alaska and Hawaii. And it was not until 1938 that most began paying benefits.

In the early years, most states required eligible workers to wait 2 to 4 weeks before drawing benefits, which were commonly set at half recent earnings (subject to weekly maximums) for a period ranging from 12 to 16 weeks. Ten state laws called for employee contributions as well as employer contributions; three still do today.

Over the following years the unemployment insurance system has been improved in a number of positive ways, including by broadening coverage and boosting benefits. However, its basic structure remains largely intact, a structure that is overly complex, with a patchwork set of state eligibility requirements and miserly benefits. And we are paying the cost today.

This history makes clear that nothing will be given to us. We need and deserve a better unemployment insurance system. And to get it, we are going to have to fight for it, and not be distracted by the temporary, although needed, band-aids Congress is willing to provide. The principles shaping the Workers Unemployment and Social Insurance Bill can provide a useful starting point for current efforts.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is Professor Emeritus of Economics at Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon and Adjunct Researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea. His areas of teaching and research include political economy, economic development, international economics, and the political economy of East Asia.

He is the author of seven books on issues related to globalization and the political economy of East Asia, with a focus on China, Japan, and Korea; his work has been translated into Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, Turkish, and Norwegian. He has also published numerous articles in journals such as Monthly Review, Critical Asian Studies, Journal of Contemporary Asia, Review of Radical Political Economics, Against the Current, and Historical Materialism.

He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Korea Policy Institute and the steering committee of the Alliance of Scholars Concerned About Korea, and has served as consultant for the Korea program of the American Friends Service Committee. He is also the chair of Portland Rising, a committee of Portland Jobs With Justice, and a member of the organizing committee of the Workers’ Rights Board (Portland, Oregon).

Spread the word