Marvin Gaye’s classic 1971 record What’s Going On turns 50 this month, which means more people than ever will have occasion to note how timely it is. “He could have written What’s Going On yesterday,” poet Nikki Giovanni noted in an interview last autumn, explaining that the cover portrait of her 2020 collection, Make Me Rain, pays homage to Gaye’s album cover, picturing Giovanni in a raincoat, her collar upturned. The record’s endurance – most movingly displayed by Nelson Mandela, who, shortly after his release from prison in 1990, recited lines from the album at Tiger Stadium in Detroit – has practically become a cliche.

No one is wrong, of course, to say that Gaye’s album cuts as deeply today as it did in 1971. A divinely inspired work driven by social rage – one that braided doo-wop harmonies, jazz and the hymns Gaye had loved as a child – What’s Going On was also Gaye’s declaration of creative independence from Berry Gordy’s Motown machine. After a decade of polished pop hits, Gaye, now in his early 30s, revealed there was a lot on his mind: the outrage of the war in Vietnam (What’s Happening Brother?); the strangulation of the natural world (Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)); the strategic enforcement of urban poverty and police violence (Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)). The insurgent subject matter was accompanied by a change in Gaye’s personal style: he stopped wearing ties and grew a beard. “Black men weren’t supposed to look overtly masculine,” he told his biographer David Ritz: “I’d spent my entire career looking harmless, and the look no longer fit. I wasn’t harmless. I was pissed at America.”

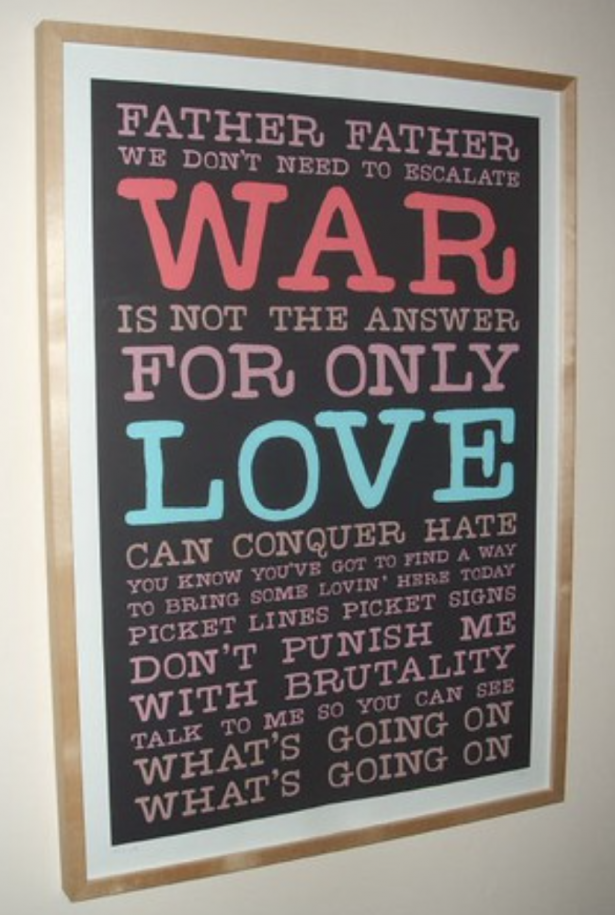

What’s Going On remains vital, above all, for how it turns away from that “America” and instead addresses the title question to a closer-knit group – those people gathered at the house party Gaye stages in the album’s opening moments; the “mother, mother” and “father father” he calls out to (and that the party setting might embolden him to candidly address). “Are things getting better like the newspapers say?” the speaker asks in What’s Happening Brother?, checking the claims of those in power against the authority of everyday Black people.

It is one thing to celebrate Gaye’s enduring and prescient mode of creation; another to applaud the continued resonance of his album’s concerns. We should not be sanguine, for instance, that Gaye’s understated blues critique of “trigger-happy policing” has stayed so relevant; or that anti-Black violence has so persisted over the last 50 years that it remains necessary for Black artists and everyday people to approach the task of surviving and thriving in America with the energy, elegance and grace that Gaye modelled in this landmark work. He might have hoped it would be more occasional, that his efforts might by now appear more dated. This, in any case, is the impression I get when watching Gaye introduce the title track at the Montreux jazz festival in the summer of 1980. Maybe he was tired – it was the last song of a long set – but the 40-year-old Gaye, in his frilled white shirt and sequinned red suit jacket, appears to not just work the crowd but pander to it with some contempt: “This was our very first No 1 record ever in the world, ladies and gentlemen. We were so proud. Thanks to you – you made it so. Hope you still enjoy it!”

He would be dead just four years later, shot by his own father in his parents’ house in Los Angeles. In the decades since, Black artists have continued to treat the lasting relevance of What’s Going On as both problem and promise. “I’m tired of Marvin askin’ me what’s going on,” Janelle Monáe sings in her 2013 track QUEEN.

This is precisely the kind of galvanising work that Gaye was doing with What’s Going On, for his own people in his own time – a historical point that is often obscured when we fixate on the record’s timelessness. Gaye’s critique of the Vietnam war, for example, which was informed by his brother Frankie’s experiences of the conflict, was disarmingly distinctive. So, too, was Gaye’s growing maturity, in which Black fans heard both his commitment to Black life and their own potential. “Beyond the brilliance of the string arrangements and the improvised basslines by James Jamerson, he was making power moves to give us what we needed,” music historian Rickey Vincent recently told me. “It was motivation music. Because we could tell Marvin was motivated.”

Vincent sees Gaye’s actions as “the driving force” behind Stevie Wonder’s political turn at Motown, as well as the rigorous funk of Sly and the Family Stone and the righteous soul of Aretha Franklin’s 1972 album Young, Gifted and Black. These stars, along with countless session musicians, were “doing their best work ever at this crucial moment in time” – setting the standard, in the case of Gaye and his collaborator David Van De Pitte’s meticulous string, conga, bass and vocal arrangements – for what Vincent calls “soul music as high art”.

To be sure, What’s Going On is an impeccably composed suite. Sonic recurrences are choreographed across the course of the LP: “What’s happening, brother?” one man asks another in the opening moments – a query that becomes the title of the next track, where the first song’s background harmony emerges as the foreground melody. But there is also a sense in which the sounds remain jarring and strange. So-called “timely” music often arrives before you know you need it, and is in that sense quite untimely: outrageous, out of joint, ill-fitting. Listen to how Gaye cranks the volume back up just as the title track starts to fade out – a sign of resilience as well as a petty refusal to let a track that Gordy hated end without a fight. Or how one man in the opening party scene greets another and then asks, “What’s your name?” Here is a conviviality you make just by showing up, where you don’t have to know someone to be glad they came.

What I listen for now are moments like these, which, despite repeated plays, cover versions and samples of Gaye’s songs, still sound discordant and unresolved. There are the searching chromatics of Save the Children: “Live life for the children! (oh, for the children),” Gaye sings, making his way up a haunting and halting musical scale, as if toward a future just out of reach. In this portion of the record, timing and melody come unmoored, as Gaye makes room for hard, even despairing questions: is it possible to “save a world that is destined to die”?

Things snap into place with the up-tempo Right On, but I still don’t know what that song is about. If at first Gaye seems concerned with parsing good from bad actors, “those of us who simply like to socialise” v “those of us who tend the sick and heed the people’s cries,” he also gathers them all into an affirmative, right-on roll call that mellows out into an oblique paean to sex: “And my darling, one more thing / If you let me, I will take you to live where love is king.” The song seems to gather all of “us” into a broad sonic space (marked by cosmopolitan instruments ranging from guiro to flute), and to make everyone’s existence holy via the sanctification of sex.

But then there are the screams. The squawking tenor saxophone solo with which Wild Bill Moore tears through Mercy Mercy Me might be the most dramatic performance of the “holler” Gaye sings about in Inner City Blues – but which Gaye himself delivers, at the end of that song, as a stylised cry: “Owwww!” It often seems to me that that holler, the culmination of the growling tones Gaye sings on the track, should be fiercer, more unhinged. What Gaye performs instead is the virtuosic, militant control required, in the midst of panic, of Black people in America, no less than in that other war overseas.

These elements are not easily absorbed or conscripted into narratives about Gaye’s moment or our own; precisely because they are the record’s jagged edges, they keep reaching out to grab listeners through time. It’s not that they speak so clearly to this moment or what it requires, so much as they remind us of the unruly ways of grief, love, and revival. How those parts of yourself you thought you had processed can come roaring back; how the people you’d given up on might suddenly come through. The record bristles, for all its impossible beauty, with unmanageable, going-on life.

Emily Lordi is a professor at Vanderbilt University and the author of The Meaning of Soul: Black Music and Resilience Since the 1960s.

Spread the word