Two years ago, Nicole McCormick was so passionate about teaching that she ran for vice president of the West Virginia Education Association. A music teacher for 11 years, McCormick “always had high expectations of what a music teacher should do,” and on top of lesson planning and caring for her family, she put in extra hours after school to make her union stronger, too.

But now she has left the classroom and is unsure if she will ever return. The increasing workload, the uncertainty and pressure of the pandemic, the combined stress of parenting her own four children, looking after her ill mother, worrying about the health and safety of her students, and the low pay and constant disrespect drove her out.

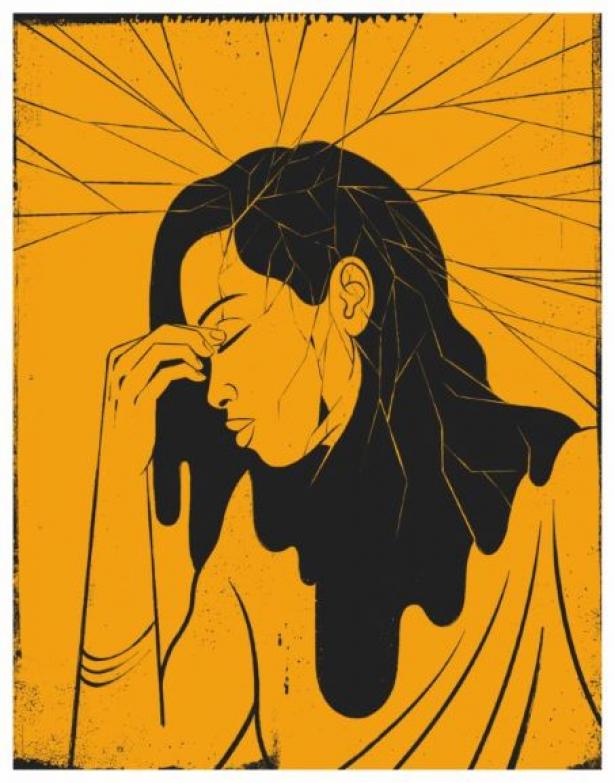

“Part of teaching is putting on a show,” McCormick said. “Because we all know that these children are living with trauma. I couldn’t put on a show anymore. Because if I did, if I successfully put on that show during the day, by the time I got home, there was nothing left.”

She is not alone. Many teachers around the country are reaching a breaking point. They have been demonized in the press and blamed for school closures, and the ways COVID-19 has dramatically changed public education have piled heavily on top of attacks and shortages educators and public schools have been enduring for years. No longer able to give their best to their students, many teachers are leaving the field and the impact on the future of public education could be catastrophic.

There are now 567,000 fewer educators in public schools than at the beginning of the pandemic, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the ratio of hires to job openings has reached new lows, with 0.57 hires for every open job. A poll released in February by the National Education Association also found that 55 percent of polled educators plan to leave the field earlier than they originally thought because of the pandemic, and 80 percent of union members reported that “unfilled job openings have led to more work obligations for the educators who remain.”

Moreover, a February report from the Economic Policy Institute noted that nearly every state is seeing “substantial losses” in public education employment, with 16 states having losses of 5 percent or more. And it’s not just teachers either. Support staff, from bus drivers to custodians, have also been leaving as districts scramble to fill positions. In Massachusetts, some 200 members of the National Guard were even called in for a couple months to help drive kids to school.

McCormick’s story is increasingly common, so much so that there’s a whole “Teacher Quit Tiktok” on the social media platform, and news organizations that spent months demonizing teachers are now running headlines like “Teachers Are Quitting, and Companies Are Hot to Hire Them” (The Wall Street Journal) and “The Number of Philly Teachers Quitting Midyear Is Up 200 Percent, and Staffing Challenges Are Likely to Continue” (The Philadelphia Inquirer). It’s part of the phenomenon known as the “Great Resignation” — in which teachers are not alone — that has seen sky-high quit rates across multiple sectors in the economy, as well as rumblings of worker unrest among workforces ranging from food manufacturing to film sets.

Kate Bahn, a labor economist at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth whose research focuses on teacher labor, pointed out that teachers’ quit rates are still lower than the average across industries in the “Great Resignation” — 0.7 percent in state and local education, compared to 2.6 percent everywhere, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — but they’re going up, and even more teachers are expressing their intent to quit. It’s worse for Black teachers “and the field is already getting whiter,” she said, citing a RAND Corporation study from last year that found one in four teachers, and almost half of Black teachers, were likely to leave their jobs by the end of the year. This is exacerbating long-term trends that see people steering away from the field or leaving teaching earlier in their careers.

“Teaching’s not easy and it’s really hard to stay,” McCormick said. “It’s hard to stay in the profession and it’s hard to stay in southern West Virginia. It doesn’t matter how much you love the place, how much you want to save it.”

In Boston, James Carroll (not his real name) also feels the strain and is looking for exits. He’s been teaching at a pilot school where teachers had been given autonomy and democratic power over how the school was run. But he feels “it has been essentially crushed by the school district over the last year and a half in both intentional and unintentionally malicious ways.” The pandemic served to separate parents and teachers from one another, he felt, and made it easier to push through changes at the school, from the scrapping of the teacher-designed curriculum to the loss of a few valued colleagues.

Like McCormick, Carroll noticed how his exhaustion and burnout made it hard to be present for his students. “I can feel in moments when I’m responding to kids that I’m like ‘This is not how I like to be responding to kids.’” So he’s weighing his options — he hopes to teach somewhere next year, but is clear that he needs out of this situation.

Susan Jones (not her real name), a teacher in Michigan, feels the stress in her body. “I wake up with migraines. I was up with stomachaches and there’s so much guilt if you try to take a day off because we’re so short-staffed. It’s slowly destroying my health and my ability to enjoy my own family,” she said.

Jones has taught for 17 years and has won statewide awards for her work as a language teacher. “Before the pandemic, even though it was rough for teachers, I would never have considered leaving the classroom,” she said. But even then, she was feeling stretched. “I went from having three schools to teaching at five schools. My first year in education, you could go into the supply room and grab pencils or crayons or paper for the kids, and now those things are under lock and key because we don’t have the money. There’s less and less to do it with, there’s more and more cost to teachers.”

And then last November, a 15-year-old student brought a gun to school and killed four students in nearby Oxford. “I was actually in the middle of a lockdown drill with my students when the shooting happened. I felt so horrible afterward because they were scared and I said, ‘I’ve been teaching for 17 years. We do this for it to be safe, but I really don’t think we’ll ever be in a situation.’ And then, at that exact same time, the shooting was happening.” She was horrified, too, to hear some in the community and the press blaming teachers for not having prevented the shooting. “Kids don’t learn from people who they don’t have trust for. So, if teachers have to become police and check everyone’s bag, then all your chances to learn and connect with that student go out the door.”

Jones is not sure what she’s going to do next, but she too knows she’s leaving. “The essential problem for myself and most teachers right now is this: If we choose the profession that we love, that we believe in, that serves our communities and the future of our country, we are also often choosing exhaustion, debt, poor health, ridicule, and no time or energy for our own families.”

***

The teacher shortage and increasing trend of teachers thinking of leaving the profession early runs counter to what research shows is necessary for learning and for children’s stability. “What we must have is a high-quality, experienced, certified, and stable public education workforce,” said Amy Mizialko, president of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association. What kids need more than anything are teachers who stay in the profession and make long-term commitments.

And teacher turnover is higher in many states hostile to worker power and with less access to public services, like Arizona, Texas, and Montana. In Arizona, there are nearly 7 percent fewer teachers now than in 2019; in Montana, it’s 9.5 percent. Conversely, union power and grievance procedures tend to help teachers stay in the profession, Bahn said, and develop the skills that make them highly effective teachers. Yet right now, the Right and many supposed liberals and public education supporters are doubling down instead on attacking teacher unions.

And it’s not enough for them to blame teachers for school buildings being closed. The Right has amplified the attacks on teachers and public education that have been going on for decades by now targeting teachers for teaching about racial justice and talking about sexual orientation. The combination of these vicious campaigns with the pandemic crisis has created a pressure cooker for many educators, but longtime teachers have dealt with these types of onslaughts for decades.

“Our great resignation [in Wisconsin] started more than 10 years ago with Act 10,” Mizialko noted. The teacher pipeline virtually dried up after former Gov. Scott Walker stripped public sector workers of collective bargaining rights, and they’re seeing the results now in staffing shortages all over the state. For the union, that’s meant a revolving door of trying to sign up new members and begging longer-term teachers not to leave.

Since the pandemic began, there have been two consistent experiences for teachers, said Barbara Madeloni, education coordinator for Labor Notes. “One is that you are on your own. And the other is that it’s absolute chaos.”

Madeloni noted that combination leads to resignation rather than organization. People quit jobs when they don’t feel capable of changing them, or when they lack the trust with co-workers to fight together. In the early days of the pandemic, there was a feeling that we were all in this together, and that, Madeloni said, everybody would want to organize around health and safety. But it turned out that parents, teachers, and students had different experiences of health and safety because of existing structural inequalities like racism, poverty, urban versus rural, and more.

Stacy Davis Gates, vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union, pointed out that for many children and teachers, the kind of instability the pandemic brought has been the norm for years. Schools closing in Chicago, after all, have seemed perfectly fine over the years to administrators when they’re in communities of color. Teachers in Chicago have been locked in an ongoing battle over school reopening with Mayor Lori Lightfoot, and within the union there has been disagreement about the right path to take. Davis Gates noted that in their strong union, there have been fewer teacher exits than elsewhere, but she’s still seeing teachers in Chicago leave too.

“My son has lost three teachers this year,” she said. “One of his former teachers is a new parent, and every day leaving the school building was completely afraid of infecting a baby who can’t be vaccinated.” Teaching is an overwhelmingly female profession and “when people talk about how difficult this pandemic has been on mothers, they often forget that we’re real people too,” she said. “Being a woman is one thing. Now layer that on top of being a woman who’s also an educator whose identity is never acknowledged as female and mother, and feeling expendable when you are responsible for your family at the same time.”

Teachers are also frustrated that the mitigations they’ve had to fight for just become more work for them. They now have to make sure students wear masks and wash hands and all the rest. They have to support students whose parents have died of the virus. They’re still getting sick, and then the workload increases as they scramble to cover one another’s classes. They use sick days to do childcare if their own children are ill or their school or daycare closes, and then if they get sick themselves, there are no sick days left. Like so many other so-called essential workers during the pandemic, the word teachers used in interviews over and over was “expendable.”

***

McCormick had hoped that the COVID-19 crisis would be an opportunity for those in power to realize what needed to be done to support teachers and improve schools. But so far, it’s been just the opposite, and teachers and parents already tired of fighting before the pandemic have been pushed to the brink.

And the disrespect for teaching has been particularly profound in these times of acute staffing shortages, when teachers see everyone from the National Guard to police to parent volunteers being drafted into schools. Even though it’s not widespread, “seeing the national guard, police, and anyone they can find called in to cover classes — instead of fully funding schools and supporting current staff — is another slap in the face,” Jones said. “It shows that to many we are just babysitters.”

The cost to those students of not having qualified, experienced teachers will be real, Mizialko noted, and National Guard soldiers will not be able to pick up the slack, nor will feel-good stories about superintendents driving the bus and mayors substitute teaching. It’s been bad enough, Jones said, for teachers to have to answer to legislators who have never set foot in a classroom, who never ask for their opinion. Now they’re essentially being told anyone can do their jobs.

Madeloni noted that the language of breaking points and of stressed mental health can lend itself to feeling further isolated, when the reality is that so many people — certainly parents and teachers — feel the same pains, the same stresses, and they’re related to working and living conditions. In this moment, she said, “The answer to the problem of our mental health is to organize not only in order to win different conditions, but because by coming together and organizing, we are transforming ourselves, creating the different experience that we want in the world.”

That organizing, Mizialko said, has to itself create space to “acknowledge the suffering and sit with it. It exists; don’t try to deny it, don’t try to pretty it up. But then how do we use that to fuel a fight?” All of the teachers interviewed for this article agreed that it has been hard to feel the kinds of connections that used to fuel their work. But in the bleakness of the past two years, the moments of connection — when a parent sends a thank-you card or the organizing that parents at school are doing — have been even more beautiful to teachers. And, economist Bahn noted, research backs up the idea that when teachers fight, the community learns better how to support them and join in the struggle.

And the end goals of that struggle are the things that, once again, social justice teachers and their unions have been asking for for years. Standardized testing seems like systematized cruelty at this point. Smaller class sizes not only to help mitigate the spread of the virus, but allow more sensitivity to the trauma and socialization needs that kids have after two years of pandemic. During hybrid teaching, McCormick noted that she got to see a slice of what it would be like to have 10 students in a class rather than 25 or 30. “I had no discipline issues when half of my students were there. I could reach the children who struggled and I could push the children who excelled. I could focus on them. I could get through twice the amount of material.”

The teachers interviewed for this article also spoke of the need for pay raises to keep educators in the profession. “I don’t see many politicians saying we need to increase teacher pay and that we need to increase respect for the profession,” Jones said.

The unions are pushing for raises, too. “Because of the shortage, it’s going to allow us to make a pretty strong appeal that we’re not going to be able to staff our schools if we don’t make this career a way so that you can live in Los Angeles,” said Noriko Nakada, a middle school teacher who also organizes with United Teachers Los Angeles. Mizialko is working on a proposal to incentivize teachers who may be near retirement to stay with financial bonuses for three-year commitments. “But again,” she warned, “that’s survival. That’s not growth.”

“If I got a $20,000 raise, I was guaranteed that my class sizes wouldn’t be more than 15 and 18 kids, we actually had collective bargaining, and my health care was affordable, I would go back tomorrow,” McCormick said, adding that she fears for the future. “My youngest daughter, who is 5, she asked, ‘Do you know what I want to do when I grow up? I want to be a teacher.’ And I would never discourage her. But in my mind I was going ‘Don’t do it. Don’t do it.’”

Madeloni pointed out that the pandemic has also proved that one of the goals of the corporate-backed “education reform” movement is untenable. “Remote learning doesn’t work for the economy, and parents hate it. So in some ways the conclusion that the elite have to be drawing is ‘We actually need a thing called schools. We thought we could just undermine them completely.’ But what does it look like for schools after they’ve lost some significant percentage of their veteran teachers? Is it Teach For America? Is it just anybody comes in?”

And to the teachers and union leaders interviewed, this feels like an emergency, not just for them, but for public schools broadly. “If people do not start speaking out and demanding that legislatures listen to teachers and support and fund our public education, I think we’re nearing the end of good public education in our country,” Jones said.

Mizialko agreed: “It feels like another Hurricane Katrina moment right now for public education. There’s this denial and refusal to publicly acknowledge that this is going down and we’re going to go down together if we don’t do something drastically different and right now.”

[Sarah Jaffe is the author of Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone.

Illustrator Adrià Fruitós’ work can be seen at instagram.com/adria_fruitos.]

Spread the word