We now live in a world where public servants informing the public about government behavior or wrongdoing must practice the tradecraft of drug dealers and spies. Otherwise, these informants could get caught in the web of administrations that view George Orwell’s 1984 as an operations manual.

With the recent revelation that the Department of Justice under the Obama administration secretly obtained phone records for Associated Press journalists — and previous subpoenas by the Bush administration targeting the Washington Post and New York Times — it is clear that whether Democrat or Republican, we now live in a surveillance dystopia beyond Orwell’s Big Brother vision. Even privately collected data isn’t immune, and some highly sensitive data is particularly vulnerable thanks to the Third Party Doctrine.

So how can one safely leak information to the press?

Well, it’s hard. Even the head of the CIA can’t email his mistress without being identified by the FBI. With a simple subpoena or warrant, the FBI can obtain historical calling information (and with cellphones, location history); email messages (and records revealing the pattern of where and when the target accessed these accounts); internet activity; and much more.

Since even separate, innocuous contacts between a reporter and source may be sufficient for the FBI to establish a relationship in its investigations — and who knows what kind of leak triggers a crackdown — here’s my guide for potential leakers.

Leaking by Email

The CIA supposedly already provided a guide to secure email, which the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) translated back to English — convenient, given the situation we now find ourselves in.

Get a dedicated computer or tablet: the cheapest Windows laptop will do. And pay cash, as our normal laptops have a host of automatic synchronization and similar services. Our personal web browsers also contain all sorts of location-identifying cookies. Even if you’re logged in to but don’t actually visit Facebook’s home page, a subpoena to Facebook can still reveal where you connect and what pages you visit — every “Like” button reports to Facebook that you are visiting that particular page, at a particular time, from a particular IP address.

Leave your cellphone, your normal computer, and your metro card (like SmarTrip) at home: anything that speaks over a wireless link must stay behind. Then go to a coffee shop that has open Wi-Fi, and once there open a new Gmail account that you will only use to contact the press and only from the dedicated computer. When registering, use no personal information that can identify you or your new account: no phone numbers, no names.

Don’t forget: if you get anything at the cafe, or take public transit, pay cash. Be prepared to walk a bit, too; you can’t stay close to home for this.

Of course, the job still isn’t finished. When you are done you must clear the browser’s cookies and turn off the Wi-Fi before turning off the computer and removing the battery. The dedicated computer should never be used on the network except when checking your press-contact account and only from open Wi-Fi connections away from home and work.

Leaking Over the Phone

Again, start by leaving all electronic devices at home. Go to a small liquor store in a low-income neighborhood, and buy a pre-paid cellphone (TracPhone or similar) with cash. Make sure it has enough airtime to not expire for a few months — T-mobile prepaid is particularly good since the pay-as-you-go plan doesn’t expire for a full year if you buy $100 of airtime.

By the way, I would personally look for a store with security cameras that look old — a continuous tape or similar setup — since once the FBI has the number, the next step is to contact the store that sold the phone. Alternatively, you can get someone else to walk into the store and buy it for you.

You now own your very own “burner” phone — remember The Wire? – and this phone must remain off with the battery removed at all times. Because every active cellphone is effectively a continuous GPS, monitoring your location and feeding the information to the phone company which retains this information for weeks, months, even years. Just a warrant-step away.

Now, to use the phone … Once again, go to a different location without carrying your normal devices, turn on the phone, check your voicemail, make your call, turn it off again, and pull out the battery. Your phone calls are now (hopefully) anonymous so that when the FBI leak-hunt starts, there is no trail for them to follow.

Of course, the burner laptop or phone could still identify you if it’s ever found, as they both contain network identifiers built into the hardware. So if you ever need to abandon your device, first wipe the device back to its factory fresh configuration using any “secure erase” options available, then take a hammer and break the device. Put it in some other piece of trash (like an empty McDonald’s sack), go for another stroll, and drop in a public trashcan.

But if the feds are already following you, you’re caught anyway, so it doesn’t matter if they catch you taking out the trash instead of finding something when they search your home.

***

All of this may seem like a script for a fictional T.V. show. But it’s the situation we’re in if you want to share information you have the right to — such extreme measures are a modern necessity.

Does whoever leaked the Justice Department’s memo justifying drone strikes on Americans need to fear prosecution? Should someone even at a seemingly innocuous agency like the FDA need the above precautions before talking to the press or Congress? Yet with prosecution’s like Thomas Drake’s — triggered by his revealing unclassified information about NSA mismanagement — its now become clear that simply leaking embarrassing information carries substantial risk.

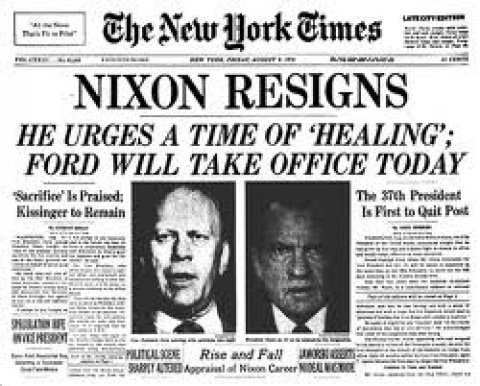

Any future Deep Throat needs to follow these sorts of procedures if he or she wishes to talk to the press … though just imagine if Mark Felt had to do all of the above when leaking to Woodward and Bernstein.

UPDATED May 15: There’s another option I didn’t originally mention here — leaking over mail. Investigative journalist Julia Angwin of the Wall Street Journal points out that physical mail, dropped in a random post-box with a bogus return address, is perhaps the best way for anonymous one-way communication. Though the U.S. Postal Service will record address information when asked by law enforcement, it doesn’t (at least currently) record this information on all mail. There’s no history. And even if there were, it can only be traced to the processing post office. So perhaps the best use of mail is simply to send the reporter a burner phone pre-programmed to only call your burner.

Nicholas Weaver is a researcher at the International Computer Science Institute in Berkeley and U.C. San Diego (though this opinion is his own). He focuses on network security as well as network intrusion detection, defenses for DNS resolvers, and tools for detecting ISP-introduced manipulations of a user’s network connection. Weaver received his Ph.D. in Computer Science from U.C. Berkeley.

Spread the word