Ralph Fasanella, the former UE organizer who became recognized as one of America’s greatest painters of working-class life and struggle, passed away twenty-five years ago, on December 16, 1997. His paintings — which he intended to be viewed in union halls, not private homes — depict a working class that is diverse, politically engaged yet exuberant in their leisure, and, most importantly, organized and willing to engage in struggle.

His large canvases of urban and workplace scenes are filled with people, each one lovingly rendered as an individual, yet tied together into a collective through Fasanella’s use of vibrant color, cutaway views and creative perspective. The figures looking out of the windows of the tall apartment blocks that form the backdrop of many of these paintings are not lonely, alienated individuals, but people fully engaged in the life of their city.

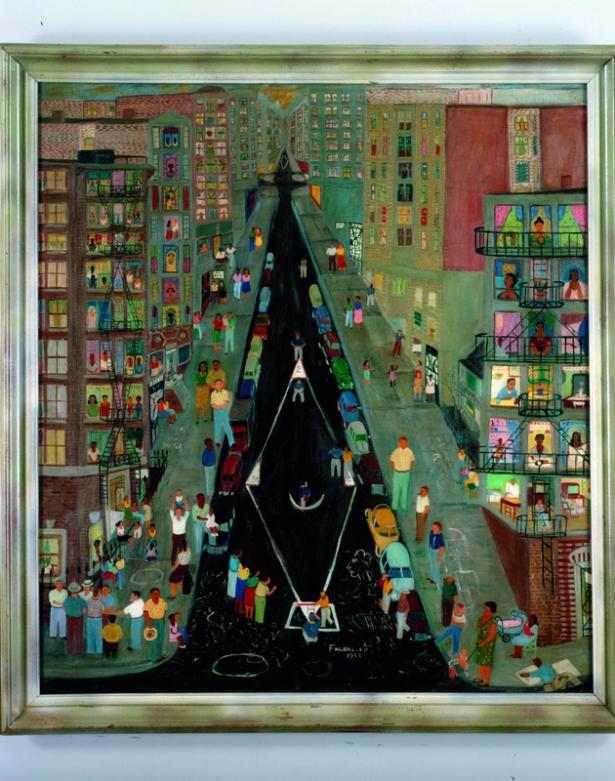

In Sunday Afternoon, from 1953, Fasanella depicts a street baseball game. The contrast of the chalked diamond against the black asphalt establishes the central story of the painting: neighborhood kids have claimed this space for play. Adults watch from the sidewalks and apartment windows above; couples stroll down the sidewalk; in the lower left-hand corner a group of men gather to chat. The human figures tower over the cars and trucks parked along the street; there are no angry motorists honking at the kids to get out of the way. As in all of Fasanella’s sports paintings, there isn’t a clear distinction between players and spectators — all are part of a whole, even those not directly watching the game.

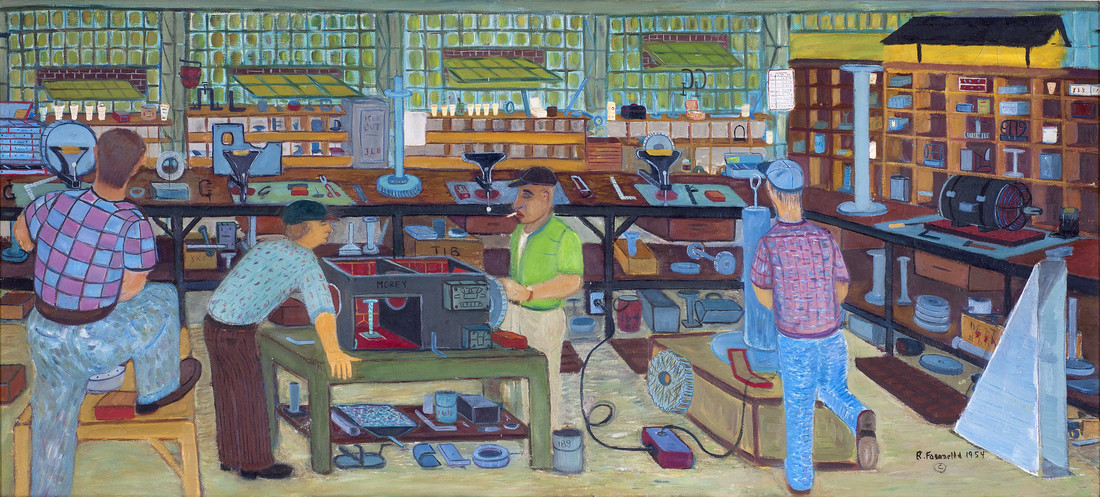

He also painted smaller groups of people — families gathered for supper, or small groups of workers. Bench Workers—Morey Machine Shop, from 1954, shows four workers, including Fasanella (on the right), who worked at Morey (a UE shop) in the late 1930s and then again in the early 50s. The workers are unhurried and confident in their skill. In the words of Paul S. D’Ambrosio, who wrote the text for a Labor Arts online exhibit of Fasanella’s work, the painting shows Fasanella’s “ideal of a humane and productive work environment: the goal of a stable union shop.”

A theme Fasanella returned to repeatedly in his work was the shop organizing committee. While not as dramatic as the marches, strikes or picket lines he also painted, a well-organized committee of workers is perhaps the single most important means for achieving that ideal of a stable union shop. Undoubtedly drawn from his time on UE staff, when he organized the Western Electric plant in Manhattan, Sperry Gyroscope, and numerous other electrical equipment and machine plants in and around New York, one of his Shop Organizing Committee paintings shows UE organizing and educational materials on the wall — “Know Your Union: UE,” a copy of the UE NEWS, a poster describing the UE steward system, and a wall chart for tracking progress in signing up members.

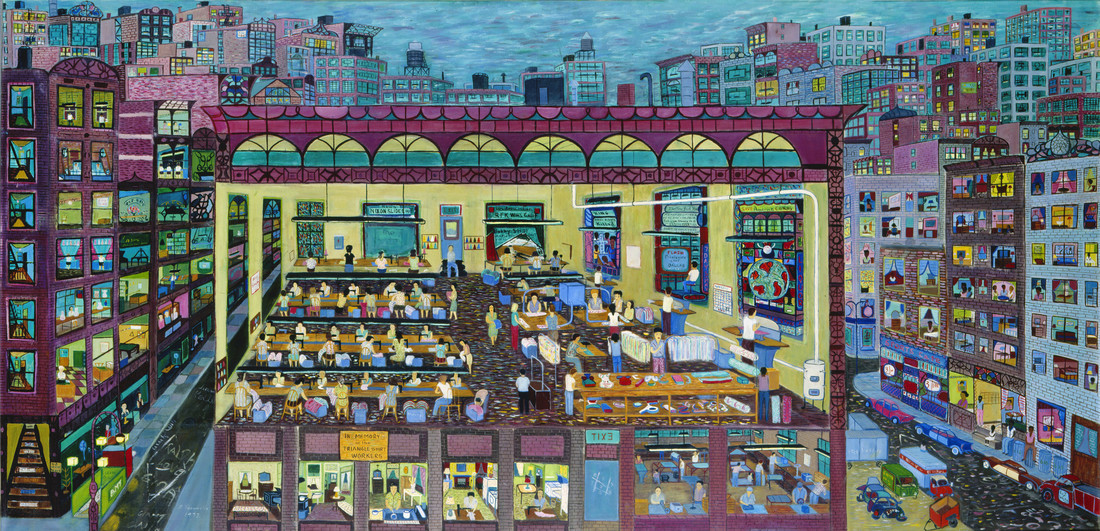

Fasanella’s paintings are infused with his deep familiarity with the rhythms of working-class life. “I loved these people,” he said of his 1972 painting Dress Shop, which depicts workers in a garment factory like the one his mother worked in, and to which he was brought as a small child. “They were a part of me. I think the painting shows a feeling for people, how they live, what they do. That’s what the painting is all about. Those people, I know them all.”

“I had to paint”

He was born on Labor Day, 1914, to working-class Italian immigrants in the Bronx. His father operated an ice truck, delivering blocks of ice in the days before electric refrigeration, and his mother worked in a garment factory, sewing buttonholes. His mother was also an active antifascist, and in 1938 Fasanella joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a group of volunteers who fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

Returning to New York City, Fasanella became a member of UE Local 1227 when he got a job as a machinist at the Morey Machine Shop in Brooklyn. He came on UE staff in 1940.

Originally taking up sketching as a form of therapy for the arthritis he suffered in his hands, Fasanella found painting to be his true calling. Asked by the UE NEWS in 1972 why he left the union’s staff in 1946, he said simply, “I had to paint. I couldn’t do both.” (Fasanella did briefly return to the UE staff in 1950 to help repel raids from other unions.)

Fasanella’s uncompromising political ideas (and, perhaps, his association with UE) led to him being blacklisted by many galleries during the red-baiting of the Cold War. He exhibited his work at union halls of progressive unions like the Distributive Workers Union, Local 65 and even got a mention in Sports Illustrated in 1956 for his baseball paintings, but was unable to support himself with his painting. As the UE NEWS reported in 1972, Fasanella was “lacklisted and hounded as many militant organizers and working people were during the late forties and fifties”; he “went from shop to shop and finally ended up pumping gas at a Bronx garage in order to keep food on the table and a roof over his family’s head.”

“A theme which has been ignored by American painters”

In that year, Fasanella’s work was discovered by the “art world.” He was featured on the cover of New York magazine, which declared “This man pumps gas in the Bronx for a living. He may also be the best primitive painter since Grandma Moses.” (The label “primitive” — which Fasanella rejected — was the term used at the time to refer to artists who had not had formal training, many of whom were from the working class, women, or people of color. Now the term “outsider art” is more commonly used.)

The UE NEWS reported that a showing of Fasanella’s work at the Automation House Art Gallery in the fall of 1972, following the New York article, drew “the sort of crowds that an exhibit of the works of an established, world-famous artist might attract.”

The centerfold UE NEWS article explained that “eople from all walks of life — working people, intellectuals, art connoisseurs, school children, black and white, rich and poor — were flocking to see this exhibit. … Readers [of the New York article] could see from the reproductions in the magazine that Fasanella was an artist with something to say and said it in terms they could understand, but which are never trite. …

“Viewing sixty of these canvases, one gets the impact of Fasanella’s life work. He has done what he set out to do, paint the heroism of the working class in the organizing struggles of the thirties and forties and the continuing struggles, the jobs and the sorrows and the hopes that make up the lives of workers and their families. ... ere, for the first time, is a body of work by an important artist that deals with a theme, which, with very few exceptions, has been ignored by American painters.”

Following his “discovery,” at age 58, Fasanella was finally able to paint full-time. One way that he took advantage of this new freedom was to travel to the mill town of Lawrence, Massachusetts, where more than 20,000 immigrant textile workers launched the famous “Bread and Roses” strike in 1912. Staying in modest quarters at the local YMCA, Fasanella walked the city, talking to residents and sketching its brick mill buildings. He eventually completed eighteen paintings which, Anne Broyles wrote in Merrimack Valley magazine in 2017, “aren’t a historical record as much as a reimagining of what life in Lawrence might have been like for the community.”

His paintings of the strike are perhaps Fasanella’s most famous. As Broyles writes,

According to Jim Beauchesne, visitor services supervisor at Lawrence Heritage State Park, the city’s “official story” considered the strike “a shameful episode in history, with outside agitators stirring up immigrant workers.” Workers were not yet protected by the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were viewed, Beauchesne says, as “beyond the pale of American society” when they protested the wage cuts that caused the workers to strike.

Just ten years later, in 1987, the city would host an exhibit of Fasanella’s paintings to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the strike, and one of his strike paintings hangs on permanent exhibition in the state park’s visitor center.

“Against the exploitation of people and places”

Fasanella’s son Marc recalls growing up in “a very activist household,” where he had “a really great relationship” with his father. Fasanella’s wife, Eva Lazorek, was involved in many social causes including the United Farm Workers grape boycott; Marc recalls UFW leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta in his family’s living room.

“Every holiday I had growing up was a political discussion,” Marc told the UE NEWS, and regular visitors to the house included UE International Representative Joseph Dermody and former UE District 11 President Ernie DeMaio, who worked at the United Nations following his retirement in 1974. The younger Fasanella praised the way his parents and their comrades connected struggles for workers rights, peace and civil rights: “They had this universal notion that we’re against the exploitation of people and places.”

He said that his father felt “disoriented” by the rightward shift of the country in the 1980s. Nonetheless, Fasanella remained connected to current labor struggles, such as in his 1993 painting The Daily News Strike, which commemorates the five-month strike against the New York Daily News in 1990-91, one of the most prominent labor struggles of the early 90s.

An Ongoing Legacy of Art for Social Justice

In 1986, UE Organizer Ron Carver launched Public Domain, an initiative to purchase Fasanella’s paintings from private collectors and hang them in public places. After his departure from UE’s staff in 1988, Carver spent two years working full-time on the project, supporting himself with consulting work. Public Domain was successful in placing a dozen Fasanella paintings in public locations in several states. Most prominently, a group of 15 unions purchased one of the Lawrence strike paintings, Lawrence 1912: The Great Strike, and donated it to Congress, where it hung for years in the hearing room of the House Subcommittee on Labor and Education. (In 1994, after the Republican takeover of Congress, they removed the painting. It now hangs at the Labor Museum and Learning Center in Flint, Michigan.)

“When I painted these things, I thought they would be hanging in union halls,” said Fasanella, commenting on the project in 1990. “That’s why I made them so big — four, five, six feet. I never really painted for individuals.”

Public Domain eventually found an institutional home at Michigan State University, which hosts the website fasanella.org.

Fasanella’s legacy lives on, not only in his artworks, but in the inspiration his work has given to others. Since his death in 1997, Fasanella’s son Marc has been managing the artist’s estate, and working to make sure new generations have access to his father’s art and vision of using art for social justice. He is currently working with Michigan State University to develop the Ralph Fasanella: Art of Social Justice Project, and with Florida Atlantic University to develop a Fasanella Fellowship in Italian-American Studies. And in 2023, author Anne Broyles will be publish a children’s picture book, I'm Gonna Paint: Ralph Fasanella, Artist of the People.

All images courtesy of the estate of Ralph Fasanella. The American Folk Art Museum in New York City hosts a large collection of Fasanella’s paintings. Reproductions of Fasanella’s paintings can be purchased from museums.co, and original paintings from Hill Gallery. Fasanella paintings will also be featured at the Outsider Art Fair in March in New York City.

Spread the word