The communication about ending the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) has been atrocious. We’re confused. Everyone’s confused. Dr. Rivers and I have been asking a lot of questions and getting some answers. Here is our understanding of the situation right now and what it means for you.

Really complex

There isn’t one national emergency declaration surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. There are five. Each has a different purpose for a different part of our government. The five emergency “buckets” are:

-

FDA

-

Stafford Act (i.e., FEMA)

-

Public Health Emergency

-

National Emergency

-

PREP Act

Together, these are responsible for hundreds (thousands?) of flexibilities that we saw throughout the pandemic. For example, the emergency use authorization for vaccines occurred under bucket #1. Extending Medicaid to more people happened under bucket #3. (This recently changed; see more below).

These different mechanisms created a complicated system that needs to be untangled without collapsing all at once. To help prevent this, the five buckets of emergencies are ending at different times. Buckets #3 and #4 are ending in May 2023. All the others are yet to be determined. (Apparently, #5 is being discussed among lawyers right now, for example).

Tools

Throughout the pandemic we’ve been told that “we have the tools.” The May inflection point means different things for different tools:

Antigen tests

Supply is going be impacted, but not necessarily because of the PHE. It’s dependent on Congressional budget. The tests are already commercialized. The U.S. bought a stockpile of antigen tests for the USPS program this past winter and still has a stockpile for the coming months. It’s not clear when this supply will run out.

The industry (i.e. test makers) are unwilling to produce a surplus of tests because demand is unknown. Without a guaranteed purchase (like from the government) or knowledge that more waves are coming to drive demand, they are hesitant to manufacture more. It’s not clear whether antigen tests, and which ones, will be available on retail shelves after the emergency like they are now.

In addition, the PHE requires health insurers to reimburse for up to eight antigen tests, per person, per month. After May, insurers will be able to choose whether to reimburse for those tests or not. We don’t have word yet, either way.

What it means for you: Don’t stock up on antigen tests just yet, as the tests do expire. But pick up some closer to the May deadline.

Vaccines

The FDA emergency (#1 above) is not ending. This means COVID-19 vaccines will still be available. BUT available is different from accessible.

Vaccines will be covered by the government until the stockpile (vaccines which the U.S. government bought from pharma) dries up. After the stockpile dries up or we get a Fall 2023 new formula booster, the vaccine will be covered by private insurance (through employment) or public insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, etc.) for the 92% of Americans who have health coverage. Most vaccines are free, with no co-pay required, thanks to the Affordable Care Act. What happens to the 8% who are uninsured? It’s not clear. We’re told there’s a plan and that they won’t be left behind. TBD.

What it means for you: Get your updated bivalent booster soon if you haven’t already. For those of you wondering if you should get a second bivalent, we may get more clarity in mid-February during the scheduled ACIP meeting.

Paxlovid

This supply is safest right now because it has the largest stockpile. In other words, the U.S. bought a ton of Paxlovid from Pfizer, and individuals shouldn’t have to pay for Paxlovid for a while. (Maybe second half of 2023, or 2024?) Once that stockpile is gone, it will be privatized. The price will be determined by Pfizer, and the price that individuals pay at the pharmacy will depend on health insurance.

What it means for you: Do not worry about Paxlovid supply for now. But this may be a problem in 2024.

Monoclonal antibodies/Evushield

These don’t work against the newest subvariants, and pharma doesn’t want to make more because the market keeps evaporating (because the virus keeps changing). For people for whom Paxlovid doesn’t work or the vaccine doesn’t confer protection (e.g., organ transplant patients), it’s not clear what protections there will be.

What it means for you: The most vulnerable will be less protected than before. Keep this is mind as you decide what precautions to take.

National surveillance

This will continue to some extent:

-

Genomic surveillance: It’s our understanding the wastewater program will remain for now.

-

Test positivity rates: Will likely go away because CDC can’t compel labs to report.

-

Hospitalizations: CDC will still get data, but the frequency will likely slow down. (Weekly? Monthly?)

-

Vaccine uptake: Will likely remain, as CDC is working with states to continue monitoring.

-

Pharmacy testing: May go away. This turned out to be CDC’s fastest way to evaluate vaccine effectiveness. So we may be going back to a delayed system to know how well our vaccines are working, which is beyond disappointing.

What is means for you: We will have “skeleton monitoring” of COVID-19. Knowing if and when we are in a new wave to inform our behaviors, for example, will get more and more challenging.

Healthcare coverage

One of the most impactful tools during the emergency was Medicaid’s continuous coverage. During pre-pandemic times, states regularly checked whether people enrolled in Medicaid were still eligible. These “checks” were removed during the pandemic. When these “checks” resume on April 1, between 5.3 and 14.2 million adults and children will lose Medicaid coverage.

(Technically, this was under bucket #3, but the Omnibus bill passed in December uncoupled Medicaid from the PHE. So this doesn’t have to do with the PHE ending, but it’s still a big change we are going to see starting April 1.)

What this means for you: If you have Medicaid, your coverage may change soon. This is particularly dependent on your state.

National vs. state. vs. local

So far we’ve discussed national implications. Of course, things gets even more complicated because each state has its own authorities and emergency mechanisms. Everything will look different depending on your state, too.

States are responsible for what the transition from Medicaid continuous coverage back to “checks” look like, for example. Some states will follow up with people to let them know they are missing information so they don’t get dropped; some states will update mailing addresses proactively so people don’t lose coverage; some states will do nothing.

Wastewater surveillance is additionally dependent on the state or locality budget, for example. In California, the state budget for COVID-19 funding will be axed by ~90%. This means wastewater monitoring in California may reduced, regardless of a CDC grant. But in places like NY, wastewater is more protected by the state.

The ultimate problem

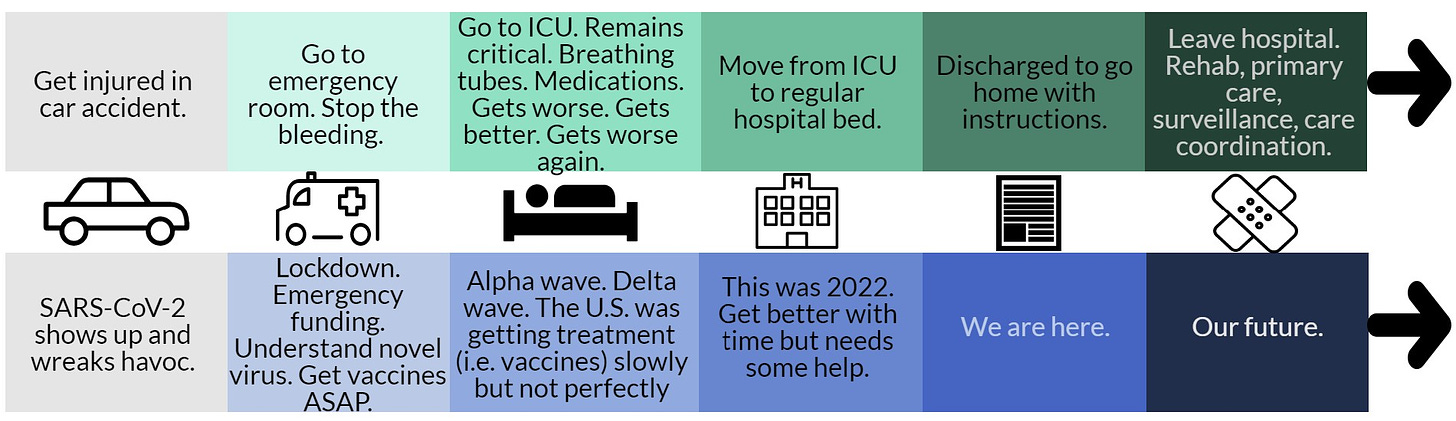

One way to think of the pandemic emergency arc is to compare it to a patient’s. For example, a patient goes through multiple stages of care after a traumatic car accident. The U.S. has gone through similar stages.

Arc of a Public Health Emergency. Figure by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina/YLE

The concern that many people rightfully have is what happens once the U.S. “leaves the hospital.” It’s a mess out there—fragmented care, underfunded public health, burnt out hospital workers, understaffed hospitals, disparities, pharma making a ton of money, expensive childcare, limited sick leave, etc. “Leaving the hospital” will mean drastically different things to different people:

-

Some will do just fine, particularly those who are healthy and wealthy.

-

Some people will do okay, like those over 65 who keep up to date with their vaccines.

-

Some people will be left behind or get really sick, like with long COVID.

Bottom line

There are still a lot of unanswered questions, and it seems like an evolving situation. This needs to be a national conversation. Participate and push. (This NYT Op-Ed was a great start.) We, as a society, need to ensure we transition NOT to a 2019 world but to a new and better 2023 world.

Love, the Katelyn/Caitlin epidemiologists

Caitlin Rivers, PhD, MPH, is an assistant professor and epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. She has her own newsletter called Force of Infection:

Subscribe to Force of Infections Here

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe.

Spread the word